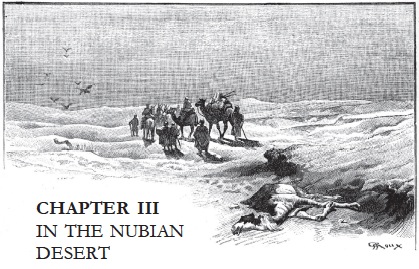

THE route taken by the little caravan led by Mabrouki Speke lies first due westward on the road to Berber, then veers to the south towards the oasis of Rhadameh. After leaving Suakim the path leads over a mountainous and broken country. But after some hours’ march the landscape changes to sterile downs stretching away out of sight to the horizon. The road is simply a pathway traced by the passage of caravans, and the simoons would cover it over with sand were it not for the sun-dried parchment-like skeletons of horses or camels to be met with here and there, and serving as landmarks to show where the path was once. This is the aspect of the Nubian desert between the Red Sea and the Nile, extending over about 110 leagues. It differs, as will be seen, from the Sahara, properly so-called, but perhaps it is even more lonely, more monotonous and desolate.

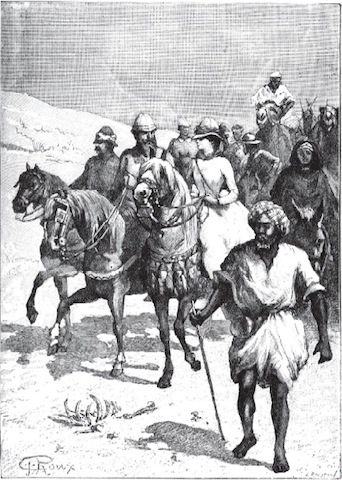

After due de1iberation the three commissioners, Costerus Wagner, Ignaz Vogel, and Peter Gryphins, had, to the relief of Norbert, decided on remaining in Suakim. He, however, could not help suspecting some sinister design to lie at the root of their decision. The expedition consisted therefore only of M. Kersain, his daughter, Doctor Briet, the baronet, and Norbert. They were all on horseback, as also were the attendants. Gertrude had donned a long robe of white linen, and wore on her head a canvas helmet and blue veil that became her admirably. Her little servant, Fatima, was in Arab costume. They headed the cavalcade, escorted by the four cavaliers, and were alternately led or followed by Mabrouki Speke.

The rear-guard was highly picturesque. It consisted of seven camels, laden with provisions, drinking-water, and camping necessaries.

Five Arab drivers, perched on camel backs between the water-skins and the bales, showed a glimpse of bronzed faces in the midst of snowy-flowing draperies. Then came two individuals of highly different aspect: Tyrrel Smith, the valet of Sir Bucephalus, philosophically enduring the hard jerky trot of his camel, and a great jolly darkskinned fellow, clothed in grey linen, with an Algerian checltiâ on his head, who was none other than Virgil, the soldier-servant of M. Mauny.

We term him a soldier-servant because he so termed himself whenever he was questioned on the point; and also because, until now, he had only served under commissioned French officers. He was an Algerian sharpshooter. The brother of M. Mauny, himself a captain in the African army, had, on learning the departure of the latter for the Soudan, hastened to secure for him the services of Virgil, who would, as he knew, prove to be a most valuable help and companion. The good fellow made no pretensions indeed to the dignity of valet, cook, coachman, or groom. A stranger to the most elementary principles of etiquette, and even to the usages of civilized life, he was nothing but a soldier’s servant—a most unique specimen though; for he was full of resources, and was indeed a Jack-of-all-trades

Just now he was vastly amused at the doleful expression on the clean-shaven countenance of Tyrrel.

“Well, friend!” he said, tapping him on the shoulder as their camels went along, cheek by jowl; “say: wouldn’t you prefer a first-class carriage?”

Such familiarity was not at all to the taste of M. Tyrrel Smith, who, moreover, had but an imperfect knowledge of French. He contented himself therefore with making a disdainful grimace, intended to express the immeasurable distance that in his mind existed between the butler of a baronet and the servant of a simple astronomer.

Led by Mabrouki

But Virgil was not going to be beaten.

He did not even notice the grand airs of Tyrrel, and if he had, he was too simple-minded to have understood them. Taking off the artistically-carved gourd that hung round his neck by a red cord, he courteously offered it to Tyrrel, saying with abroad grin,—

“Taste that, comrade, and tell me what you think of it!” This act of politeness touched Tyrrel Smith. He had a special weakness for French cognac, and without waiting to be pressed, he put the neck of the gourd to his thin lips and took a good long draught. This sacrifice to Bacchus unloosed his tongue, and enabled it once more to speak French.

“A queulle heure...nous...arriver...hotel?” he asked, with a visible attempt at graciousness.

“At the hotel!” exclaimed Virgil. “You don’t mean to say that you expect hotels to spring up in the Nubian desert like mushrooms? We shall probably halt about midnight for three or four hours’ rest, and after a slight snack, start off again.”

“But...the gentlemen...and the ladies?” said Tyrrel.

“Well, the gentleman and the ladies will, like us, take a nap under their rugs, and after eating a morsel, will get into the saddle again.”

“Je disapprouvais...hautement...pour...Sir Bucephalus!”

Emotion would not let him proceed further; his professional gorge rose at the idea of his master being subjected to such a roughand-ready style of living, and he was seized with an attack of ill-humour that lasted until at midnight a halt was called at the place fixed by Mabrouki, the meeting of the routes to Rhadameh and Berber.

They had all bravely weathered this first stage. In the twinkling of an eye, the Arab servants had lighted torches, posted picquets, pitched tents, and spread out the pro-visions on carpets, around which the hungry travellers seated themselves with appetites sharpened by six hours’ travelling.

Tyrrel Smith noted with dismay the total absence of plate. He solemnly entered his protest against such a violation of sacred etiquette by standing bolt upright all supper-time, motionless and sullen, with white gloves and cravat, behind his master.

At the end of the collation, Gertrude and Fatima retired into one of the tents, whilst the three Frenchmen and the baronet took the other; and all gave themselves up to repose. It did not last long. They had not slept an hour even, before they were awakened by the sound of voices and the stamping of feet. Fatima crept out of the tent to reconnoitre.

“It is a Berber tribe going to the Mogaddem of Rhadameh. There are a hundred at least, and all on donkeys.”

“I must see them!” exclaimed Gertrude, hastening to rise and join her father and the other travellers, who were already on the qui-vive.

The Berbers were, in fact, all mounted on diminutive donkeys, which they led with only a halter. They had women with them, and about a dozen children, who were absolutely naked, and whose first thought at the sight of a pool of water near the encampment was to rush into it and splash about.

The new comers soon gave evidence that they also meant to pitch their camp. But they were not long about it, and soon absolute silence once more reigned in the desert.

Suddenly an unexpected tumult aroused the weary travellers.

“What is that?” exclaimed Gertrude, not a little alarmed.

“Only a donkey braying,” replied Fatima.

It was indeed a young ass testifying its delight in the enjoyment of fresh water and food, in much deeper and more prolonged notes than are emitted by its European brethren. The elegant solo lasted quite three minutes.

“At last!” exclaimed M. Kersain, when it had finished. “It is time!”...

But another ass took up the song in a higher key. “Good heavens!” groaned Fatima, “now they are all going to tune up!”...

“What do you mean?”

“Oh, mistress, I know them well. When one begins, they all follow in succession...There are more than sixty of them. They will go on for at least three hours.”

“Are you sure?”

“You will hear!...I know them well,” replied Fatima piteously.

“Then we must not expect to get any sleep?”

“No, indeed!”

”Well, that is pleasant news!”

The same sort of colloquy took place probably in the other tents, judging from the angry voices proceeding therefrom. And all the while the monstrous serenade continued, being taken up by a third, a fourth, up to the fiftieth ass in succession. Tyrrel Smith could stand it no longer, “Will you be quiet, you horrid beasts, who will not even let a gentleman sleep?”...Seizing a stick dose at hand, he rushed to the asses and began beating them as hard as he could.

They all at once set up a perfect chorus of frenzied braying, which so enraged Tyrrell Smith that, losing all control over himself, he laid about him more violently that ever, regardless of the vociferations and screams of the indignant Berbers.

Virgil now came up in his turn.

“Stop!” he cried. “You will only excite them still more. I know how to silence them; come with me.”

Calling the other servants, he gave them their respective instructions, and in an instant, to the general surprise, the horrible din gave place to a profound silence.

His plan was very simple. Knowing that donkeys cannot bray heartily unless their tails are in the air, he thought of forcing them to lower these appendages by grouping them round the provision bales, and then fastening their tails to the cords of the bales. The donkeys found this argument unanswerable. After a good laugh at Virgil’s plan, everyone settled once more to sleep.

At four o’clock in the morning, Mabrouki’s rattle gave notice that it was time to start. The travellers were coming out of their tents one by one, when they were startled by the sound of Virgil’s voice pitched in a high key.

“Dogs of Arabs! Gaol birds! You shall pay for this!”

”What is the matter, Virgil?” exclaimed M. Mauny, running up.

“The matter,...why, those dogs of black devils have decamped with all our provisions!”

”You don’t say so!”

”Look, then! They have carried off everything, meat, preserves, biscuits,...even the water-skins!...and that must be out of sheer mischief, for they had plenty of water without taking ours!”

”We must set to work to pursue them,”said Norbert, “they can’t have gone far!”

”What do you think about it, Mabrouki?” said M. Kersain.

“I think it will be useless;...supposing we do overtake them, they “”ill have already hidden the provisions in the sand. and as soon as they see us they will hasten to disperse.”

“‘Well, what are we to do, then?...we are not going to die of hunger!”

”There is one thing to be done.”

“What?”

“Go to the Zaonia of Daïs, and buy some provisions.”

“Is it far?”

”Three leagues off towards the east. But the road IS too bad for the horses.”

“In that case what is the alternative?”

“If you like, I will go there with two men and two camels, and will rejoin you at the first halt. You have only to keep due south;one of the Arabs will guide you.”

This plan was approved and put into execution at once.

Mabrouki left whilst the tents were being struck.

At this moment appeared a strange being, whom it was difficult to recognize for the correct and irreproachable Tyrrell Smith. It was himself, though, but in a deplorable condition; he was wet, muddy, and covered with dung from head to. foot. He was greeted by a general peal of laughter.

“I can’t understand it,” he said. “It must have rained in torrents. Look what a state I awoke in.”...

“This is getting serious!” said Virgil, as if seized with a new idea.

He ran to the tent of the model servant, and found it flooded. The ground was nothing but a vast puddle, in the midst of which floated the leather skins, once full, but now quite empty.

“This is another trick of those dogs of Berbers,” said Virgil. “It is their return for the cudgelling you gave their young donkeys.”...

“Let us be thankful,” said the doctor, “that they have not taken the water-skins.” He was of a very optimistic temperment. “At least,” he continued, “we can fill them from the pool yonder.”

“Yes,” said Virgil, “fill them with nigger-boys’ dishwater!”

”How so?”

“They have so well stirred it up that there is not a drop fit to drink. It is only mud.”

To their annoyance they found this but too true. The indignation of Tyrrel Smith knew no bounds.

“There is no more water? “he cried, in a voice strangled with emotion.

“Not a drop!”

”But how,” said he, red in the face with anger, “but...comment...moi...préparer...le tub de Sir Bucephalus!”

”His what?”

”His tub...his bain...; there!”...

“Ha! ha!” laughed Virgil, “that is the very least of my anxieties, I can assure you.”

This was not very consoling for Tyrrel Smith to hear. The march was resumed, although it must be owned in a somewhat spiritless manner, for no one would have been sorry to have had something to eat.

Virgil, at the last moment, was seen to be actively enga.gcd in collecting twigs and handfuls of dried herbs which he made up into a bundle.

“Are you afraid of being frozen on the way? and do you intend lighting a fire on your saddle-bow?” asked Tyrrel, who was still smarting from the previous ridicule of the other. “You have guessed exactly right,” imperturbably answered Virgil.

Before starting afresh, he loaded his camel with two enormous bundles of wood and four empty water-skins.

The sun was not yet visible above the horizon. The air was fresh and balmy; and the travellers, as they went along conversing cheerfully, ended by forgetting that they had had no first breakfast, and that the second was problematical. Dr. Briet, as curious as ever about the mission of M. Mauny and his committee, made three or four fresh attempts to extract an answer. But the young savant skilfully parried his questions, and as to the baronet, it was much if he answered even by a monosyllable.

After three hours’ march they reached a little grove of thinly-planted sickly-looking trees. The ground was covered with a kind of moss, and with tufts of grass so fine and silky in appearance as to resemble spun-glass.

Here they encamped afresh, on the Arab declaring it to be the meeting-place Mabrouki had fixed upon. But they searched in vain for the water the verdure had seemed to promise; there was not a trace of any.

Two hours had gone by and Mabrouki had not returned.

The sun was now high above the horizon, and the heat overpowering. Our travellers began to feel the pangs of hunger by this time.

“We have guns,” said Virgil suddenly. “I don’t see why we should wait any longer for our breakfast!”...

And before anyone had time to ask for an explanation of his worus, he had fired at and brought down two birds resembling pheasants, whom his piercing eye had descried peacefully slumbering on the top of a palm-tree.

No more was needed to arouse the whole feathered population of the grove, and with loud cries a number of birds flew up to the sky and descended after a few minutes. Virgil had already lighted a splendid fire with his two faggots, and was soon busily engaged in plucking his pheasants. Norbert and the baronet, following his example, soon brought down a Gozen birds of varied plumage. The main part of breakfast was thus amply provided for, but, as Gertrude remarked, a little bread would not be amiss.

“Bread!” cried Virgil. “Nothing easier; we shall have it in a quarter of an hour...Hi! comrade!” he went on to Tyrrel Smith, \vho with arms akimbo, stood looking at him, “come on with me! “

He drew him towards a kind of ravine made by the rains. In it grew a sort of reed two or three yards long.

“What will you do with this, pray?” asked Tyrrel, in a bantering tone.

“With these reeds?...I’ faith I don’t quite know.”...

“They are not reeds. They are what we in Algiers term sorglzo, and are here called dlzoura...not, perhaps] of a first-rate quality, but it is Hobson’s choice...We will begin with gathering in the harvest, and then we will turn ourselves into bakers.”...

While speaking he cut with his pocket-knife several sorghoroots heavy with grains, made them into a sheaf, and took them back to the camp. The grains were perfectly ripe, and were easily crushed between two stones.

“But,” observed the Doctor, “water is essential in order to make bread.”

“I think so, too,” answered Virgil. Groping in his pocket, he drew out a leaden ball, and carefully loading his gun with it, he looked about him. At a distance of about thirty yards stood an enormous and strangely-shaped fig-tree, the trunk of which was entirely bare. Virgil took aim at it.

“Good!” cried Smith. “He has found a target.”...The shot took effect. In an instant a stream of fresh limpid water was seen to spring from the wounded tree.

Fatima stood amazed, and felt inclined to look upon worthy Virgil as a magician. He had seized a ‘water-skin, and was hastily filling it at the improvised fountain.

“See what it is to be practical!” exclaimed the doctor.

“I knew that the tribes of the Soudan were in the habit of scooping out the trunks of certain trees in order to make reservoirs of them, carefully closing them up afterwards; but I should never have looked for one in the fig-tree, neither should I have thought of opening it in that manner.”...

“It was not my invention,” modestly said Virgil. “I learnt it from the Touaregs. They generally fire at their reservoirs in order to open them, and as the fig-tree looked like one, I thought it well to make sure...But see! my water-skin is nearly full... Please hold it under the fountain, Monsieur Smith, whilst I get the other skins off the back of my camel...”

The Doctor went back to the travellers, who were sitting in the shade under the tent, and told them of Virgil’s new exploit. They all went off at once to see the marvellous tree and drink some mouthfuls of water.

When they reached the foot of the fig-tree they found Virgil in a state of the greatest excitement.

“There is no more water!”...he cried out...“and I don’t know what has become of the Englishman with the full water-skin I entrusted to him...Smith!!...Monsieur Smith!!!” he screamed at the top of his voice.

“What is the matter?” repliecl a voice in the distance from a tent.

“I want to know where you are, and above all, where is my water?” .

“The water?...Here, of course!”...

The phlegmatic face of Tyrrel Smith now appeared at the opening of the tent.

Virgil ran up, followed by all the travellers. An unexpected sight met their eyes.

The model domestic had extracted from his inexhaustible portmanteau a splendid gutta-percha tub, and. spreading it open, filled it with the contents of the waterskin, not keeping even a drop to appease his own thirst; he had poured in a flask of toilet vinegar and thrown in a gigantic bath sponge. With a satisfied look, and a white bathing-dress on his arm, he now bowed to Sir Bucephalus, and said solemnly,—

“Your bath is ready, sir! “

Virgil had to be forcibly held down. otherwise Tyrrel Smith would have been strangled.

“Insufferable blockhead! “exclaimed the baronet, , you are at it again!”...and tmning to the others he said,...“Mademoiselle, messieurs, I don’t know how to apologize,...believe me, I had nothing to do with this incredible stupidity of my servant...I don’t know why I don’t throw him into his tub, and hold his head under water till he is done for.” No contrition appeared, however, on the countenance of the model domestic. He was simply astonished at the scolding, for was it not the duty of a good valet to prepare his master’s matutinal bath?...Virgil, left to his own devices, would soon have opened Smith’s eyes to a different view on this point, but luckily for the ears of Tyrrel Smith a fresh incident turned up in the arrival of Mabrouki Speke.

Mabrouki Speke had been detained longer than he wished by bad roads and by the dilatory ways of the Zaouia people. But here he was at last, with provisions, fresh water, and everything needful... There was no room now for any feeling but that of amusement at Virgil’s mischance, and the latter soon laughed as heartily as the rest, resolving, however, to keep a sharp look out in future over the proceedings of his comrade, Tyrrel.

The journey was completed without further incident.

Resuming their march at sunset, they halted at midnight, to proceed afresh at four o’clock in the morning, hoping in this way to reach the residence of the Mogaddem soon.