“I LIKE M. Mauny very much, certainly,” said the French Consul next morning, as he took his seat opposite his daughter at the breakfast-table. “The doctor declares that he is a most distinguished savant. He has good manners; besides, he is evidently energetic, and in addition, as a set-off, he is a good-looking young fellow.”

“In a word,” answered Gertrude, with a slightly embarrassed laugh, “he has quite made a conquest of you, dear father, and perhaps,” she continued, with a touch of malice, “he will be more pleased than surprised when he knows it.

Consul. “They are always ready to pick out the faults in their sincerest admirers. For I could see that he was smitten wjth you...But, of course,” he continued, good-humouredly pretending to take her at her word, “if you do not like him, it is as well that I should know it at once. He has just sent me a line inviting us both to go over the Dover Castle this evening; but I can go alone, and make some excuse for you!”

“An excuse for not going over the Dover Castle? You are laughing at me, dear papa,” she answered quickly. “Rather do I want an excuse to see it?...I am most grateful to M. Mauny for inviting me. And, to tell the truth, I meant to give him a hint last night at dinner when I spoke about the tapering masts that have been a three days’ wonder to the world of Suakim; but I feared it was but a waste of breath, and that he would never descend from the transcendental heights of astronomy to notice, still less to gratify, the curiosity of such an insignificant individual as myself.”

“You were mistaken, you see,” said M. Kersain. “Well then, it is settled. Be ready to go out at sunset, about five o’clock, and a boat shall be waiting at the quay.”

So saying, the Consul buried his head in the newspapers, which he generally read during breakfast. Gertrude left the room a few minutes afterwards to make her preparations, chatting the while with her little Arab maid Fatima. She was waiting for her father, gloves buttoned, at least an hour before he came to fetch her.

Suakim is by no means a large town, and in three minutes the father and daughter reached the quay. They saw Norbert Mauny at once. He seemed to be awaiting them in company with a stranger, and he now came up with great eagerness.

“We scarcely dared to hope that Mdlle. Kersain would do us the favour of accompanying you,” he said, pressing both the hands held out to him. “Let me introduce you to my friend, Sir Bucephalus Coghill; he is a member of our expedition, and, with myself, will have much pleasure in doing the honours of the Dover Castle.”...

Sir Bucephalus Coghill, Baronet, was a tall, slender, elegant young man of twenty-s.ix years of age. His florid complexion bore evidence to his Anglo-Saxon nationality, but he appeared fitted rather for the hunting-field than for a scientific expedition. He had, however, been a great traveller, and he was soon engaged in lively conversation with the Consul and his daughter.

Norbert, though, was quite taken up with what was passina at the distance of a few paces in a group composed of several Arabs, three Europeans, and an old negro habited in white linen acting as interpreter to the rest.

“It is Mabrouki Speke!...You have got hold of him already,” said M. Kersain, observing the direction in which the young astronomer was looking.

“Yes, he is trying to negotiate on our account with some camel-drivers, but he does not seem to be making much way with them.”...

Only in the East, indeed, would it be possible to hear such a medley of cries, groans, and curses as proceeded from the aforesaid group, conspicuous among whom was a great bearded, hook-nosed, turbaned fellow, who vowed he could not accept a centime less, swearing by Allah and the infernal powers that by the head of his father he would be reduced to die of hunger! But all this eloquence had little effect on the Europeans. One of them now left the group, and, coming up to Norbert, said abruptly, with a very Teutonic accent,—

“These dogs ask ten piastres a camel, and will not give in.”

“Allow me to introduce you to M. Ignaz Vogel, one of the commissioners of our expedition,” said Norbert Mauny, in a cold tone.

The guide was not, indeed, very presentable—squinting, under-sized, covered with rings and trinkets, his miserable little body clothed in a large-checked costume, with the tiniest of hats set on a great shock head of hair, his hybrid language, accompanied with a sinister smile, made up a whole that filled one with disaust and suspicion.

“Permit.me to leave you for a minute for an important matter,” said Norbert to his guests.

They bowed assent.

“Ten piastres?” he resumed in an aside to Vogel. “And how many camels?”

”Twenty. five, at ten piastres a head. I think it exorbitant.”

“No. It is nothing, on the ccntrary. Have you considered the distance they will have to traverse?...Would that we had five hundred camels at that price instead of twenty-five...Engage them at cnce, but be careful not to let the men see that we have such need of them.”...

“Very well,” replied the other; “I will manage it.” Then, turning to the Consul and his daughter, he added: “Monsieur and mademoiselle, I will not say good-bye, but au revoir. I shall have the pleasure of seeing you presently on board.” So saying, with a parting salute in the shape of a scrape of the foot, he went off to his camels.

“A strange associate, truly, for Monsieur Mauny and that correct young Englishman,” observed M. Kersain and Gertrude to each other.

But the pleasure of embarking in a canoe soon effaced the disagreeable image of Ignaz Vogel. Six sturdy sailors, rowing well together, brought them in two minutes to the stairs of the Dover Castle, whose captain awaited them with a courteous greeting.

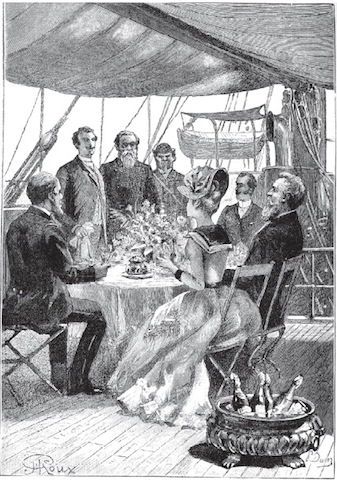

They duly admired in extenso and in detail the cleanliness, discipline, and good order that reigned everywhere, and asked, as is usual, a thousand explanations that were all forgotten the next minute. They were told the name of every little bit of rope, and initiated into all the customary rites of the occasion. At length, when everything had been lauded to the skies, came the chief rite of all, the luncheon, which the two young men had ordered to be laid out aft under an awning.

The table was covered with fruit, ices, and pastry, embedded in flowers; and, to the great surprise of M. Kersain and his daughter, there was a profusion of superb plate and rare china. The Consul could not refrain from complimenting M. Norbert.

“All these splendours are due to Sir Bucephalus, and not to me,” laughingly replied the young savant. I am not in the habit, I assure you, of always eating off silver plate or drinking tea out of porcelain cups; but the three other commissioners and myself take our meals with Sir Bucephalus in common, and this is the Asiatic luxury he shares with us.”

“No luxury could be too great to honour our present Guests,” said Sir Bucephalus. “But I must beg them to believe that I could very well dispense with it, only my domestic tyrant will not allow me to have my own way.”

“Sir Bucephalus,” explained Norbert, “possesses a model valet, who has grown up in the shadow of the ancestral manor, and would deem it a crime not to regulate his master’s life in accordance with the laws of etiquette.”

“He knows very well, at least, how to decorate a table,” said Gertrude; “these pomegranate blossoms have a charming effect.”

Tyrrel Smith, the valet in question, coming up at this juncture with the champagne, the conversation was changed, and before very long joyous peals of laughter resounded over the calm waters of the Red Sea.

In the midst of their cordiality Ignaz Vogel made his appearance, escorted by the two individuals they had seen with him on the quay. Norbert at once introduced them as—

”M. Peter Gryphins...M. Costerus Wagner, commissioners of the expedition.”

The three new-comers seated themselves at table without ceremony.

“More commissioners,” thought Gertrude. “They look rathe.r like servants out for a holiday. M. Mauny has certamly been unfortunate in his choice of commissioners.”

“Have you succeeded in settling your business without being outrageously cheated by those cunning rascals?” asked the consul. He was by no means fascinated by the oddities whom he was addressing, but he tried to be amiable out of compliment to his host.

“Damn it!” elegantly replied Peter Gryphins, who might have come straight from a stable, judging from his scanty waistcoat, his gaitered legs, paper collar, and bookmaker’s visage. “We have scarcely nobbled thirty-five camels, instead of the fifty that were promised us.”

“These Arabs make a boast of fooling us,” added Ignaz Vogel. “I am very doubtful whether we shall succeed in getting the necessary means of transport.”

“Do you need, then, such an enormous number of men and beasts?” asked the Consul.

“We want at least eight hundred camels,” replied Norbert, “and a proportionate number of guides. It is a question of disembarking all our material and conveying it to the table-land of Tehbali-that is to say, about eight hundred leagues off, across the desert. It is no easy matter, I know. But the thing ·will be feasible if only the bad faith of these people does not raise insurmountable obstacles.”

“Mr. Peter Gryphins, Mr. Costerus Wagner.”

“Why did you not tell me sooner of your difficulties?” cried theConsul. “I could have saved you many useless comings and goings...You must know that in any great undertaking there is nothing to be done throughout the Suakim territory, unless you treat directly with the real lord of the land?”

”And who is he?” asked Norbert.

“He is a local ‘saint,’ Sidi-Ben-Kamsa, Mogaddem of Rhadameh, and head of the powerful tribe of the Cherofas... Not only will no camels be forthcoming without his permission, but if you had had the imprudence to bring any from Egypt or Syria, you would assuredly have been attacked and robbed in the desert.”

“Are you speaking seriously?” exclaimed the young astronomer.

“Most seriously. You must indubitably win over this high personage to your enterprise, or give it up.”

“And how can a humble wretch like me manage to gain the protection of a holy mogaddem? It seems more difficult than to get hold of those slippery camels,” said Norbert.

“Good...Have you forgotten that a golden key will open many doors?”

“How? Would the saint be amenable to mercenary sentiments?”

”Between ourselves, I believe he knows no other.

Sidi-Ben-Kamsa is one of the most singular phenomena of this country. It is to him that recourse must be had for everything and on every occasion. He gives audience every morning at sunrise, like the Commander of the Faithful in the’ Thousand and One Nights.’ His receptions are much sought after, and it would be supremely inconvenient to go there empty-handed.”

“No matter,” gaily rejoined Norbert. “We are quite prepared to go with full hands. Is it far from here?”

“About two days’, or rather two nights’, march.”

“We should not do ill to go and visit this holy personage tomorrow. What say you, Coghill?”

“I say that the excursion would be a real pleasure party if M. and Mdlle. Kersain will come, too,” answered the baronet stolidly.

“Mdlle. Kersain!”...“My daughter!”...simultaneously cried Norbert and the Consul.

“Oh, a thousand thanks, monsieur!” exclaimed Gertrude, quite delighted. “You could not have proposed anything that would please me better. If my father will only say ‘Yes,’ I undertake to show you that a woman can travel in the desert without being in anyone’s way...Oh! dear papa, do consent!...You know that for a long while I have been dying to see this famous mogaddem...I promise to keep well, darling papa, and not to tire myself.”

“Very well, very well,” smilingly answered her father, who had no wish to refuse his daughter· the promised pleasure, and was only fearful of intruding. “But are you quite sure that we shall not be in the way, Monsieur Mallny?”

”Oh! Consul, has not Sir Bucephalus told you that if you come the journey will be turned into a party of pleasure? But it will be fearfully dull if we are not to have your company after having hoped for it.”

“It is very gracious of you to make me so welcome. It is settled then. For a long while past my brother-in-law, Doctor Briet, has been urging us to make this strange excursion with him. He shall join us if you consent, and I make no doubt but that he will be ready to start as soon as you like.”

The baronet and Norbert bowed their assent. As to the three “commissioners,” no one noticed their presence, or seemed to consider them as forming part of the expedition. But the one whom Norbert had called Costerus Wagner, and who. from his large flapping hat and long trailing yellow hair, might very well pose as a savant at large, suddenly said,—

“Do you think it necessary for Vogel, Gryphins, and myself to make this journey?”

“By no means,” answered Norbert, most significantly; “and if you prefer to remain here and superintend the landing of the material-”...

“The landing is the captain’s affair,” interrupted Peter Gryphins, in a sullen tone. “And the statutes are precise; we ought not to leave you.”...

“The statutes having been drawn up at my suggestion, there is no need to quote them to me,” replied Norbert, with an irony in his voice that escaped neither the Consul nor the “commissioners.” The latter made a visible grimace.

“I think our best plan is to entrust Mabrouki Speke with all the preparations,” said Norbert to the Consul; “and if it is agreeable to you we might start to-morrow.”

“To-morrow night,” replied M. Kersain; “for, as you doubtless know, one can travel only at night and morning in this climate...Shall we meet at six o’clock at the Consulate?”

”Yes, at six o’clock.”

“How pleased I am!” cried Gertrude,· delighted.

“Thank you, dear father! Thanks a thousand times, messieurs! ...Sir Bucephalus, it was you who proposed that I should be of the party. I thank you, then, more especially!”...

Norbert had some trouble to dissemble his piqlle at this expression of gratitude, natural and unaffected though it was.

“...There is that fellow, Coghill,” he thought,” already on the best of terms with Mdlle. Kersain! . “I shall never know how to get on with her; I seem lacking in the art or gift, whichever it is...Perhaps I have been so long taken up with telescopes that I have forgotten how to talk to ladies.”...

M. Kersain perceived his abstracted air, and rose to take leave of his hosts, who, however, insisted on accompanying him and his daughter to the very door of the Consulate.

Returning to the Dover Castle, they met Mabrouki Speke on the quay, and gave him their orders. l’he old guide knew his work. He listened attentively to their instructions, and promised that all should be ready for the start. at the appointed hour on the morrow.