IT was seven o’clock in the morning, and the sun already scorching, when Mabrouki Speke, pointing to a white speck on the summit of a hill at the horizon, said,— “There is Rhadameh!” Every spy-glass at once leapt out of its case, and disclosed to view the dome of a minaret whose white walls glistened amid the surrounding verdure.

“We shall be there in forty minutes,” added the guide.

“And it will not be a moment too soon,”...exclaimed Mdlle. Kersain, putting her hand to her white linen helmet, “for this martial head-covering is really suffocating, and yet I dare not take it off.”

“Indeed you must not!” answered Norbert, anxiously. “You would have a sunstroke, which would be anything but pleasant.”

“Perhaps you would rather that some one else should have one—myself, for instance!” laughingly observed Dr. Briet, as he vigorously wiped his forehead. “The heedlessness of these young astronomers is something deplorable,” he continued; “what on earth would become of the expedition deprived of its head doctor? ...And yet I may take off my helmet as often as I like, without you noticing it.”

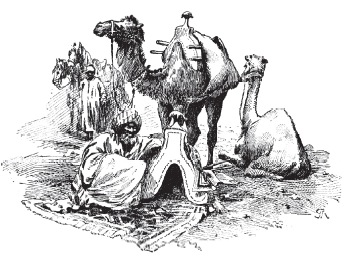

In less than half-an-hour the little caravan reached the foot of the hill. The horses and camels went lightly up the stony road, and soon came to a waste piece of ground, bounded on the east by the walls of the Zaouia. This is the name given in Mahometan countries to the convents or stations that serve as sees or residences for the ecclesias-tical dignitaries. The travellers dismounted amid an ever-increasing crowd of pilgrims of every condition, colour, and age, who had all come to consult the famous Mogaddem. There were negroes from Darfour or Kordofan, Arabs wrapped in their wide burnouses, Turks in their baggy trowsers,—Jewish merchants even were to be seen spreading out their poor merchandise in the midst of the horses, asses, and camels. Some of the asses were uncommonly like those who had been so suddenly cured of their musical mania by Virgil two nights previously; but it was impossible in such a bewildering crowd to identify either the asses or the Berbers, whom they had only seen at night-time. So no one even tried to do so; they were in too much haste to expedite matters, and to see the Mogaddem.

The latter received the homage of the faithful in a large paved hall, opening outwards by two double doors. The entrance was free to all the world, and our travellers passed in with the others.

Their first impression was one of physical pleasure in exchanging torrid heat and blinding sunshine for the delicious coolness of a vast vaulted nave, that was lighted only from above by windows of stained glass. When their eyes had become accustomed to the semi-obscurity, they perceived at the further end him whom they sought.

The holy man was seated cross-legged in the middle of a wonderful square carpet, whose brilliant colours were the only relief to the dead whiteness of the bare walls. He wore a wide cotton shirt, and a white turban was tightly wound round his head. He sat motionless with downcast eyes, as if in deep meditation. His leanness was extra-ordinary. Although, to all appearance, scarcely more than forty years of age, his coal-black beard was thickly strewn with silver. The skinny fingers, dried up as those of a mummy, slowly passed the beads of a heavy amber rosary; indeed, but for this movement, he might have been thought lifeless, for no sound, not even a sigh, issued from the half-open lips, and even the long eyelashes lay motionless on his cheek. The faithful crowded round the carpet, and followed with eager eyes the slow passage of the beads that dropped one by one from the Mogaddem’s fingers. From time to time a row of musicians seated against the left wall beat upon their drums with the palms of their hands. This was the signal for a lugubrious groan that resounded through the hall, whilst all the faithful were seized with a simultaneous holy shudder. They were evidently in expectation of something, and they did not always wait in vain. A stick of dried wood, thrown as if by chance in front of the Mogaddem, would suddenly rise up hissing, and glide with a wavy motion to his venerated feet. The stick had become a serpent!...The faithful rush to save the prophet...when lo! the serpent stretches out its head and quietly subsides into merely a stick once more!...

A halt in the desert.

Or again, numbers of white pigeons flying through the narrow opening in the roof, would hover round the saint, and at a word, or even only a sigh, from him, hang motionless in the air, as if suspended, three feet above the earth. . . . Another sign or sigh and, behold, they all fly away!...The faithful were lost in a stupor of amazement at seeing such prodigies....At each fresh signal they tore off in feverish haste everything valuable they had about them—a silver-mounted poniard, or silken purse, or perchance a curiously chiselled cocoa-nut, and flung all at the feet of the saint.

He took no notice, and appeared as if rapt in ecstasy. Only if some object of greater value was offered him, such as a piece of silk or a wooden bowl filled with gold-dust, or a fragment of ivory, he would heave a sigh, and, raising his heavy eyelids, murmur a few words in reply to the supplicant’s question.

At his right hand stood a singular being, a kind of deformed dwarf, who made hideous grimaces, and attracted the attention of the visitors almost more even than the Mogaddem.

He was not taller than a child of four years old, although his shoulders were of an extraordinary width. He was, in fact, as broad as he was high, and his brawny muscular arms hung down nearly to his enormous feet. A complexion black as ebony, an abnormally wide mouth, snub nose, and little eyes hidden behind thick spectacles, stamped him a perfect monster. His costume was a red silk blouse, confined round the waist by a wide blue sash; white pantaloons, yellow boots of morocco leather, and an immense white turban, from which his beard appeared to be growing, so short was the space between his forehead and his mouth.

This dwarf was apparently dumb. He stood on the edge of the carpet, about two yards from the Mogaddem, on whom he kept his spectacled eyes fixed, without seeming to notice the strangers near. But every now and again the dwarf and his master exchanged mysterious signs that struck terror into the spectators. Doctor Briet whispered to Norbert that he fancied he recognized the mute alphabet.

At the near approach of our travellers, this singular being was evidently disturbed. A gesture of admiring surprise escaped him. His eyes shot out fire from behind his glasses. But it was only for an instant that his habitual calm was thus troubled; he quickly resumed his passive contemplation of the Mogaddem, whose ecstasy had not been interrupted in the least.

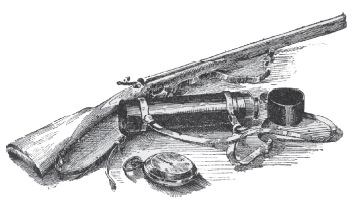

Meanwhile Mabrouki, the guide, spread out on the carpet the gifts, without which it would have been the height of bad taste to have approached the holy man. The ascetic physiognomy of the Mogaddem assumed an expression of earthly delight on beholding at his feet a gold chronometer, a spy-glass, a double-barrelled fowling-piece, and a china crape shawl. A glance escaped from under the piously downcast eyelids, and with a deep sigh the saint awoke from his silent contemplation and looked with benignity on the new faithful.

Norbert came to the front then, and couched his request in the requisite formula through the medium of Virgil, who repeated his words in Arabic.

The Mogaddem, who had fallen back into deep abstrac-tion again, with closed eyes and hands crossed upon his rosary, now roused himself afresh to consult his dwarf. The latter made several rapid signs, then prostrating himself on the ground, he struck it thrice with his forehead.

After a fresh interval of silence, the Mogaddem mur-mured in a squeaky voice some words that Virgil hastened to interpret.

The holy man was quite willing to assist the travellers with the services of his children, the braves of the tribe of Cherofa. But it was first necessary to consult the oracle. . . .

“What oracle?” asked Norbert.

“The oracle of the holy Sheikh Sidi-Mohammed-Jera’ib,” said Mabrouki discreetly, whilst the Mogaddem, who had resumed his ecstasy, gave no more sign of life....

“And where does this new saint hang out?”

“In his tomb, five hundred paces off,” gently answered the old guide, whom a long experience of Europeans had accustomed to their audacity of language. “Only,” he added in an aside, “it will cost another pretty sum!”...

“What matter, if it is necessary!”

“And besides, it may be amusing!” said Gertrude, who was always ready for novelties in the way of wonders.

The travellers sallied forth to find the tomb of the sheikh, without paying any more attention to the Mogaddem and his dwarf. It was moreover evident, from the renewed abstraction of the holy man, that he considered the interview at an end.

They caught sight of the tomb on a waste piece of ground three or four hundred yards from the audience-hall, and beyond the precincts of the Zaouia. It was not worth while to remount, and the party traversed the short distance on foot.

They had taken about twenty steps when Gertrude stumbled over a stone. At one and the same moment the baronet and Norbert rushed forward with extended arms to her assistance. Gertrude could not but laugh at their haste, and not wishing to slight either, she took both arms held out to her. This way of settling affairs dis-pleased each of them, and they both went away sulkily, to her increased amusement.

“What a monster that dwarf is!” she cried. “Did you notice his resemblance to a monkey? I wonder what is the secret of his influence over the Mogaddem...for it is evident that the saint undertakes nothing without his advice!...”

“They must have done some bad business together,” said Norbert in a tragic tone.

“Why such a supposition as that?” answered the baronet. “Would not their faith be a sufficient link?”

“Faith in the power of money, you mean, doubtless,” rejoined the young savant ironically. He had not failed to note the stealthy glance the Mogaddem had cast upon the gifts.

“Well! That is perfectly compatible with more noble convictions,” replied Sir Bucephalus. “What can be done without money?”

“ I am inclined to think that the dwarf is simply the Mogaddem’s appointed conjuror,” said the doctor, who, with M. Kersain, had been listening to the little discussion. “Did you notice his Indian costume? In Bengal I have often seen the like marvels done by the jugglers of the country. I have seen them make serpents out of wood, paralyze pigeons, and perform even greater wonders still.”

“Those are enough, I am sure!” exclaimed Gertrude. “How on earth do they manage to arrest the flight of the pigeons and keep them perfectly motionless in the air?”

“Probably they only appear so, whilst in reality they are slightly fluttering their wings; they are under the .influence of a kind of magnetism. But in India I have seen something much more wonderful. I have seen a child of seven years old raised in the air to the height of three feet like the doves just now.”

“You saw that yourself?”

“I seemed to see it. And there was no cheating; there were no suspending cords, no supports of any kind. The phenomenon is inexplicable by any of the known data of European science, and it is not the only one of the sort....For instance, on another occasion I saw a Bengalese magician scratch up with his nails the parched soil in a garden alley, then plant in it a camellia seed, which germinated under our eyes, and in a quarter of an hour it became a plant covered with flowers.”

“Wonderful!...”

“It was all an illusion of the senses, due to the prodigious dexterity of the conjuror. But I have seen these Indian fakirs and jugglers perform other marvels that I scarcely dare to relate to you, so inconceivable are they. These people have a host of traditional secrets touching upon phenomena scarcely known as yet to modern physiology.”

Conversing thus, they reached the tomb of the sheikh. It was a small square edifice made out of one block, five yards long and four wide, overshadowed by three elegant palm-trees.

At the entrance, two dervishes with parchment-like countenances and shaven heads awaited the visitors. They came forward, bowing profoundly, and on learning from Virgil that it was a question of consulting the oracle, demanded a preliminary contribution of five piastres a head. Pocketing this, they announced that the visitors must enter the sanctuary barefooted.

Our travellers were obliged to submit, and left their boots therefore at the door.

Suddenly a fresh difficulty arose. The dervishes objected to admit Mdlle. Kersain and Fatima. But this scruple quickly melted under the influence of another gold coin.

At length the matter was settled, and they all went into the holy tomb. It proved to be a bare hall containing only a carpet well worn by the knees of the faithful. At the right angle stood a kind of cup or vase of grey marble without any apparent opening. One of the dervishes explained, through the medium of Virgil, that it received questions, and gave forth the answers of the oracle, but that the sacred formula must first be uttered.

“Very well!” said Norbert, shrugging his shoulders. “Let us have the formula then, Virgil, since we must say it.”

The two dervishes, now prostrating themselves on the carpet, lifted their hands above their heads, and said an Arabic prayer together.

Virgil repeated it slowly so that his master might articulate each word with him, which the young man did, not without evident impatience.

“Now,” said the dervish who took the lead, “let the stranger lord address himself directly to Sidi-Mohammed-Jeraïb.”...

“Confound it!” said Norbert in an aside, “the oracle really ought to speak French....”

“ I speak French!”... at once answered a sepulchral voice, issuing apparently from the bottom of the cup.

This unexpected manifestation so astonished the visitors that they were at first stunned. Mdlle. Kersain turned pale. Fatima’s eyes dilated with fear, and she seemed on the point of fainting.

But Norbert soon shook offhis emotion, that sprang from surprise only, and he now bent down to the vase with a smile upon his lips.

“Sidi-Mohammed-Jeraïb,” he said, “since you know French so well, we can talk freely. I am in need of your powerful assistance, in order to obtain the necessary means of transport from the tribe of Cherofa, your beloved daughter. Will you help me?”

At the name of the saint the two dervishes had thrown myrrh into the lighted censers hanging from their sashes, and swung them to and fro. A thin thread of smoke rose up, filling the hall with a penetrating perfume. The voice of the marble cup answered,—

“You must first tell me what has brought you to the Soudan, and what end you have in view.”

The young astronomer could not repress an involuntary gesture of astonishment, whilst his travelling companions drew nearer to hear the interesting dialogue.

After an instant’s hesitation, Norbert thought he had better continue the conversation.

“I have come,” he replied, “to study the wonders of the heavens, and for this purpose I mean to erect an observatory on the table-land of Tehbali.”

“You are not telling the whole truth,” replied the oracle. “You have a more audacious scheme in view!”...

For an instant Norbert was put out of countenance, and lield his peace.

“I am omniscient,” resumed the oracle. “Nothing escapes me. I know the present, the past, and the future. Shall I prove it to you by saying what you seek to do on the mountain of Tehbali?”

“Say on,” said Norbert merrily.

“Laugh not!...Your levity is ill-timed...for your undertaking is a most foolish one....You are come hither to contend against the eternal laws that regulate the Universe....If you are our friend, we can but pity you, inasmuch as you will be vanquished in the struggle....if you be an enemy, Nature will take our vengeance upon herself!”... It is impossible to give any idea of the effect this sinister prediction from an invisible mouth produced upon the audience. Norbert laughed no more. His reason could scarcely master the stupor that came over him on hearing the replies given by the oracle. But still he was loth to believe that any one at Rhadameh could really know his secret.

“ Think you,” resumed the voice in terrible accents, “that anything concerning the people of Allah can escape me ? Your scheme had not been formed three minutes ere it was known to me!...You have the presumption to aim at suspending the course of the moon, to attract it to the earth and render it accessible to human cupidity!... That is your senseless scheme!...But I here tell you that it will not succeed!”...

Norbert and Sir Bucephalus looked at each other in amazement. Was it possible that their secret had been violated?...How could the pretended oracle know it? The only explanation they could think of was that one of the commissioners left behind at Suakim must have been indiscreet, and the betrayed secret, travelling faster than the caravan, had preceded them to Rhadameh....

It was indeed astonishing to meet with it here through the invisible agency of an intelligence that could speak French, and whose voice issued from a marble vase!...

Doctor Brief was evidently most deeply interested in the revelations. His twinkling little eyes went from Norbert to Sir Bucephalus, trying to read their faces and find out whether what the oracle said was true. Not less great was the surprise of M. Kersain and of Gertrude. As to Fatima, she had fallen on her knees as soon as the voice first spoke, and, hiding her face in her hands, gave herself up to superstitious terror. And no wonder ! For it would have tried stronger nerves than those of the little servant to have heard the terrible voice issuing apparently from the earth; the effect heightened by the sighs of the dervishes who were squatting on the carpet, and the aromatic perfume that in spiral clouds of bluish colour rose up from the smoking censers....Virgil alone took it philosophically, looking round him with all his accustomed sang-froid.

Norbert was the first to recover himself.

“Well,” he said imperiously, “if you know our scheme, you also know that it is in nowise inimical to the Arab people....Yes or no; will you help us to the necessary means of transport?”...

“I will,” said the oracle.

Then suddenly condescending to earthly details, he continued,—

“You must pay in advance ten piastres a head for every man or beast, and in seven days the 800 camels you require shall await you with their guides under the walls of Suakim.”...

“That is what I call speaking to the point,” cried Norbert gaily, “and this oracle evidently knows how to do business!...To whom must we pay the 16,000 piastre?”

“To the envoy of the Mogaddem, who will fetch them, and will give a receipt at the French consulate.”

“That is settled, then....But tell me, Sidi-Mohammed Jerai’b, is our alliance to end with the transport?”

“It will endure so long as you regularly pay tribute to the Mogaddem.”

“What tribute?”

“That which is due to him, if you wish his children to protect you in the desert, and give you the assistance you need.”

“How,” said Norbert, rather ironically, “would they lend themselves to an enterprise that you disapprove?”

“ Yes; if you pay the tribute, they will not trouble about your plans.”

“And how much is it?”

“Twenty times twenty piastres a month.”

“I willingly agree,” replied Norbert.

“Then farewell...and may Allah go with you!”

With these words a lugubrious groan issued apparently from the vase. The dervishes arose, and slowly intoning a psalm in a low voice, they retreated backwards to the entrance, swinging their censers the while. The visitors instinctively followed their example, and, still under the influence of the astonishing scene, put on their shoes in silence. Fatima was so completely stupefied by it all that she stumbled over her Turkish slippers, and would not have found them again, had not Virgil picked them up and put them into her hand.

They now set off towards the encampment chosen by Virgil at a few paces distant. He had already pitched their tents, and had brought thither the fresh provisions they had procured at the Zaouia. After a little while they all began to exchange ideas concerning the strange facts they had witnessed. Norbert alone remained silently buried in his own reflections.

None of them could understand it. That there was some clever jugglery behind was plain, but how was it managed? How was it that the oracle could give such an exact statement of the young astronomer’s project? The doctor especially was devoured by curiosity.

“Come, Sir Bucephalus,” said he merrily to the baronet, “you who are in the conspiracy can tell us if the oracle was right!... There is Mdlle. Kersain dying to know the truth. Will you leave her to find it out from M. Mauny?”

“Speak for yourself, uncle,” exclaimed Gertrude, with a merry laugh; “don’t try to hide your curiosity under cover of mine. You know that you have been in an agony for three days to find it all out!”...

“I acknowledge it,” replied the doctor. “But I swear that my curiosity is purely in the interests of science.”

“M. Mauny,” observed M. Kersain, “did not certainly contradict the oracle. But if he does not see fit to trust us with his plans, we have no right to force his confidence.”

“Bosh !” responded the doctor, “ when the secret is flying about the desert!”...

At this moment, Norbert, who was walking on in silence, turned round, and addressing the consul and his daughter, said,—

“The oracle made use of a very simple artifice. There is evidently an acoustic tube connecting the Zaouia with the tomb of the sheikh, and thus enabling the Mogaddeni to hear and answer the questions; unless, indeed, it is mere ventriloquism. But still there remains to be ex-plained how it is that this fellow can speak French, and, above all, how he has managed to ascertain my project ...For, as a matter of fact, he did not tell any lies....I have in reality come to the Soudan in the hope of getting hold of the moon,... and under pain of being taken for a fool, I must now explain how I intend to set about it....Do you not think so, too?” he added to the baronet.

“Most decidedly,” answered the latter.

“Well, then,” pursued Norbert, “if Mdlle. Kersain and these gentlemen will grant me patience, I will recount at breakfast-time how the idea, which must seem so scatter-brained to them, first came into my head....I don’t ask them to agree with it as practicable. I only beg them to believe that I have good reason not to deem it such utter folly as the sheikh pretends to think....

This was a delightful announcement to Doctor Briet, and as they had now reached the tents, all sat down to breakfast. When the dessert was put on the table, the young savant redeemed his promise. We will content ourselves with giving the substance of his account, adding several details concerning his associates that a natural reserve led him to suppress.