DINNER was over: the company had passed into the drawing-room, where large bay windows stood wide open to the motionless expanse of the Red Sea, now slowly darkening in the twilight of a lovely evening in January.

M. Kersain, the French Consul at Suakim, was entertaining that night M. Norbert Mauny, a young astronomer who had been particularly recommended to him by the Minister of Foreign Affairs. The official letter intimated that the Consul would do well to put himself at the entire disposal of M. Mauny, and to assist him as far as possible in the scientific mission that, in a confidential postscript, was stated to be of a secret nature. No one, therefore, had been asked to meet the young savant, with the exception of the lieutenant of the ship, Guyon, who in Suakim waters was in command of the Levrier, the French despatch-boat.

The Consul was a widower. The honours of the table had been gracefully done by his daughter Gertrude as mistress of the house; and now seated at the piano, she was softly playing a nocturne of Chopin.

The weather was soft and mild. The dinner had been most joyous, its official character notwithstanding, for the quartette, albeit strangers heretofore, had conversed together with the delight and friendly recognition that is so customary among Parisians wheresover they meet. The last stories of the Boulevards were laughed over: mutual friends were discovered at every turn. When coffee came, the talk became more intimate, and the Consul thought it time to put a question that excited his curiosity. “You have come to the Soudan on a scientific mission,” said he to Norbert Mauny. “Is it indiscreet to inquire what kind of mission it is?”

”Not at all,” replied the young man smiling, “and your question is only natural, Monsieur le Consul. But will you be offended if I say that I cannot gratify your legitimate I curiosity, because the business that has brought me to Africa must remain an absolute secret if possible?”

“Secret even from Captain Guyon and me?” replied M. Kersain, looking slightly astonished. “There is nothing political, I presume, about your mission? The minister’s letter stated that you were an astronomer belonging to the Paris Observatory, and, if I am rightly informed, one of the most distinguished among our young savants.”

“I am in point of fact an astronomer, and it is in this capacity that I have come to Suakim. There is nothing political about my mission. But it is an unknown one hitherto in this country, and for this and many other complicated reasons, I think it best not to divulge its nature, not even to the representative of France. This was the understanding with which the Minister of Foreign Affairs recommended me to you. And, moreover, not only is my mission not political; it is purely of a private nature. The expenses are borne by English capitalists. The colleagues who came with me in the Dover Castle are none of them French. We have come to Africa to make an· ingenious experiment. The sole favour I have asked from our Government is its moral support in case of need. This was promised me by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who assured me also that I should always find him ready to assist me in the task I have undertaken.”

Whilst Norbert Mauny gave these explanations, the French Consul and the naval lieutenant observed him narrowly.

He was a tall, slender, dark young man of about twenty-six or thirty. Refined broad brow, clear bright eyes, aquiline nose surmounting a well-defined mouth, firmly moulded chin; one and all were instinct with frank bravery and goodness. He wore his evening black coat with the ease of good breeding mingled with the careless nonchalance usual in men of action. His voice was deep and melodious; speech short, and to the point. Serious without pedantry, a hidden gaiety peeping out in every deed and look, he was a fine type of a Frenchman—one might say of a great Frmchman, so evident and undeniable was the superiority of his nature.

Satisfied with the result of his scrutiny, the Consul courteously hastened to change the conversation.

M. Kersain was a distinguished diplomatist of the old school, who would have attained to the greatest eminence in his profession. had he not been kept by the shores of the Red Sea by his unfortunate passion for Nubian antiquities and the need of a warm climate for the health of his daughter. . Gertrude was twenty years of age. Frail and bending like a reed, with a milk-white complexion, and a profusion of magnificent golden hair that almost weighed her down, it was easy to see that her life hung upon a thread. Her mother, indeed, had died young of consumption, to the life-long grief of M. Kersain; and he was in constant dread lest the daughter might develop the same too well-known symptoms of decay. From time to time a slight cough shook the lovely but delicate frame, whilst an alarming flush coloured the white cheek. Gertrude paid no attention to these signs; she was gentle and charming, the idol of all who approached her, and she was full of hope, as is so often the case with these perfect beings, “too pure for this world.”

But her father could not be blind to the alarming symptoms; and the doctors were on’the alert to warn him that a less dry climate might prove fatal to Gertrude. For the sake of his daughter, therefore, he had remained at Suakim, which had been the scene of his dibut in the consular career. Every moment that he could spare was devoted to her, and to watch over the health of his child was the sole aim of his life. Her happiness was his constant thought, and he could refuse her nothing. Unselfish and modest by nature, the sweet and well-trained girl had but few caprices, but these were gratified without hesitation by her adoring father. The reticence of the young astronomer had, in despite of himself and his host, lent an air of restraint to the conversation. It was, therefore, a relief to all when a fresh guest appeared, in the person of a florid, sprightly man of about fifty—Dr. Briet, the uncle of Mdlle. Kersain, who had travelled to Suakim on purpose to take care of the health of his niece. Not an evening passed without his appearance at the Consulate, and his entry now was the signal for a joyous welcome.

“Good evening, uncle!” cried Gertrude, flying into his arms.

“Allow me, dear docteur, to present you to our compatriot, M. Norbert Mauny...M. le docteur Briet,” added the Consul, introducing the two men to each other.

They bowed, and the jovial doctor said simply at once, and with great cordiality,—

“‘I knew of the arrival of M. Mauny, and of course he was already known to me by repute. No one can read the Records of the Academy of Science without learning that M. Norbert Mauny has done magnificent work with the Spectrum analysis, and that he discovered two telescopic planets, Priscilla and...what the deuce do you call the other one?”

”She is not yet christened, except with a number,” laughingly replied the young astronomer. So many planets are discovered in these days,” added he modestly, “that it is difficult to find names for them all.”

“Call it Gertrudia,” said Captain Guyon, looking at Mdlle. Kersain.

“Oh! Captain!...You don’t mean that!” exclaimed Gertrude.

“But, on the contrary, it is an excellent idea,” replied Norbert; “and I shall be only too delighted to profit by it, if your father and yourself will give me permission. A definite name is much wanted by these little stars, to dis· tinguish them clearly from the others. Gertrudia will be perfection...I adopt Gertrudia!”

”Oh, papa, what fun!...I shall have a star to myself!” exclaimed the enchanted child. “But you will point it out to me, will you not, sir, that I may know it when I see it?”

”Most willingly...when it is visible!...in seven or eight months’ time, if the weather allows.”

“One cannot see it every night, then?” asked Gertrude, slightly disappointed.

“Oh! no...If so, it would long ago have been discovered and named... But we have found out enough about its habits now not to let it go by without an au revoir.”

“It is not everyone who can offer such a bouquet as that to a lady,” said the doctor. “And, doubtless,” he continued, all unwitting of indiscretion, “you are engaged on an astronomical mission?”

“Not precisely!” replied Norbert, who could not help laughing this time. “I see,” he added, on perceiving the astonishment of the doctor, “that it is not easy to keep a secret, especially when one is resolved to tell no lies in its defence. I might have said that I wanted the clear sky of the Soudan for the purpose of taking fresh interplanetary observations...I prefer to tell you a part of the truth...I have come here to study the ways and means of a somewhat chimerical undertaking, or, at least, such it will appear in the eyes of many when they hear the programme. Now, unfortunately, at the University I have already got the character of being a hare-brained individual. I am therefore condemned necessarily to silence about my plan until it succeeds—under pain of being looked upon and perhaps treated as a lunatic...In these circumstances you will understand my having solemnly resolved to say nothing about it to anyone. If I succeed everyone will see it!...If not, there is nothing to gain by being laughed at, and having perhaps fresh obstacles added to those that already confront me...The first step will be the establishment of a scientific station on the tableland of Tehbali, in the desert of Bayouda.”

“A scientific station in the desert of Bayouda!” cried the doctor. “What a time to choose for such a thing! Think you, forsooth, that our friends the Sou danese will let you settle it all at your ease?...I wouldn’t give a hundred pence for the skin of any European who tried even to reach the Upper Nile. And you think to cross it, and get to the Darfour frontier?...Allow me to tell you that this is simple folly.”

“Did I not say that you would call me a lunatic at the first word! “coldly replied Norbert. “You are witnesses, all of you, that I was right!”

”I’ faith, I’ll not retract!” answered Docteur Briet. “To try and penetrate to the heart of the Soudan is quite as hazardous as it would be to go among the Touaregs. Have you forgotten the fate of all who have ventured south of Tlipoli—Dournaux-Dupéré in 1874, my brave, good friend Colonel Flatters in 1881, Captain Masson, Captain Dianons, Docteur Guiard, the engineers Roche, Beringer, and so many before their time?”

“I have forgotten nothing,” said the young astronomer, with perfect sang froid. “But the geological and sidereal conditions that I need are only to be found together in the desert of Bayouda, on the table-land of Tehbali. I must seek them there.”

“Beware lest you find something quite different!” exclaimed the Consul significantly. “Believe an old African—there is only one way now to go to Darfour: with a regiment of Algerian sharpshooters and a convoy of three thousand camels.”

“I see myself, indeed, at the head of so many sharpshooters and camels!” gaily answered the young savant. “I have done my twenty-eight days twice, just like any one else, but I have never got beyond the grade of corporal, nor commanded more than four men. I must content myself with my servant Virgil, who happens to be an old African sharpshooter, and with a good guide, if I can find him At all events, the Soudanese will see that I come in friendly guise.”

“A giaour? Not they! Go and ask them what they think about it, and then come and tell them, if you have a tongue left to speak with!”

“You are certainly bent upon making me think that I am going to embark on something superhuman. Are these Soudanese, then, such fearful1y wicked people?”

“They have no intention of letting any European come out alive from among them-that is all I can tell you...And there are two or three million of them at the least perfectly disciplined, blindly obedient to their chiefs, armed to the teeth, with immense resources at their disposal...Have you never heard of the Mahdi?”

“The Mahdi?...That kind of Mussulman illuminati, who organized a revolt on the Bahr-el-Ghazel, two or three hundred leagues off?”

“Just so. Well, Monsieur Mauny, this Mahdi, if we do not take care, will eat us all before the year is out. He will drive us from Suakim, from Khartoum, and from Assouan. Perhaps he will drive us out of Cairo, and even Alexandria!”

“But have not troops been sent from Egypt to oppose him?”

“He will make but a mouthful of them, if he does not even force them to serve under him. I know what I am talking about, I tell you!...We are beginning a sacred war. In six months, or at most a year, the Mahdi will be at Khartoum!”

”A year; that is a long time! Perhaps I shall not want so long to realize my project.”

The docteur contented himself with throwing up his arms to heaven.

“So,” said the lieutenant of the ship to Norbert Mauny, “you persist in running into the lion’s mouth?”

“Yes, captain.”

“Well! you are plucky for an astronomer!”

Everyone had listened to this discussion with great interest, but Mdlle. Kersain more than all. Whilst Norbert Mauny described his plan, and Docteur Briet set forth his objections, she remained silent, her large eyes looking from one to the other; but every now and then she grew pale with the thought of the dangers to which the young savant was going to expose himself, whilst she was full of admiration for the tranquil courage with which he accepted the programme. Her expressive and sensitive countenance showed so visibly the emotions that agitated her, that her father, feeling anxious, made a sign to the docteur to change the conversation. He rang at the same time for tea, which was brought by a little Arab servant, and dispensed as usual by Gertrude. Drawing Norbert Mauny aside, the Consul led him out on the terrace, where, taking him by the arm, he said,—

“Do you know I have serious scruples about lending my countenance to such an enterprise as yours?”

“It is settled then, that you go?”

”What am I to do?” replied the young savant, very simply. “I am not alone! Considerable capital is embarked in the undertaking. A superintending committee accompany me on the Dover Castle which brought us here with all our requisites. And I repeat, what I am about to undertake is only possible in the Soudan. Besides the fact that, to my certain knowledge, the indispensable physical conditions are found together only there, the very state of existing anarchy is one of the reasons that have confirmed me ; for this frees us from tiresome negotiations and authorizations that we should perhaps never have got from an established Government. We shall work in a region that is dependent on no one, since all nominal authority even is at an end. These are precious advantages, and it would be folly not to profit by them.”

“But how do you propose to overcome the notorious and implacable hostility of Arab tribes who will bar your passage?”

“In the simplest way in the world. By converting them into friendly allies.

“And you expect to succeed in so doing?”

“I hope so.”

“I cannot agree with your sanguine expectations; but if you are really determined, you must at least take all possible precautions. We have here at Suakim a man who may be useful to you from his knowledge of the customs and men of the country. His name is Mabrouki-Speke. He is the old negro-guide who accompanied successively Burton, Speke, Livingstone, and Gordon. Shall I put you into communication with him?”

“By all means. I am only too glad, of course, to increase my chances of success....It will take some time to organize the expedition, on account of the heaviness of the baggage and requisite material. Doubtless I shall often have to come to you for help before I leave Suakim.”

“Make all possible use of me,” replied the Consul, with a cordial grip of the hand, as they returned to the drawing-room.

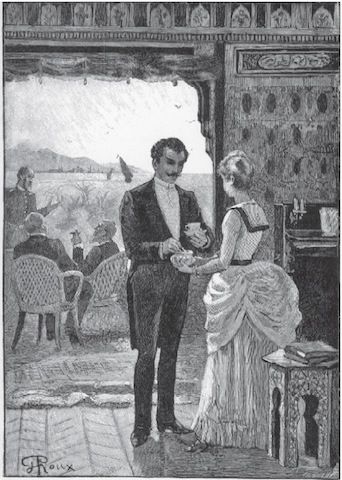

Gertrude came forward at once with a cup of tea, which she offered Norbert.

“It is settled, then, that you go?” she asked, as she handed him a piece of sugar.

The ingenuous expression of sadness on her countenance went to the heart of the young man, and he felt, to his surprise, grieved, as if about to leave a well-loved sister or one of childhood’s friends. Suppressing the sigh that rose to his lips, he smiled in reply,—

“I go, but not directly. The preparations will take two or three weeks, and so I do not bid adieu yet to the Consulate of France.”

Gertrude said nothing. Her eyes were filled with tears.

She bowed slightly, and stepped on to the terrace to gaze on the myriad stars that irradiated the heavens.