"Why are you not happy, Herr Benito? We have a half day off." The new butcher's helper, Hans Knefler, glanced over at the man he'd been assigned to work with out of the corner of his eye as they walked home from work. Benito never looked particularly happy to Hans.

"Kid, if we didn't work in a grocery store, it would be a full day off. You know all about Thanksgiving right? The Pilgrims, the New World, the Indians, yadda yadda. Big deal! Back up-time, we used to call it Turkey Day. Almost every family cooked one. Shoot, I knew a family of vegetarians and even they cooked a turkey. On Thanksgiving we ate turkey and watched the Macy's Parade on TV. And then we could watch football. All day. I loved it."

"They all had Spanish turkey?"

Benito snorted. "Not at these prices. Back then we had big farms that raised thousands of them and shipped them out dressed and frozen. Benito paused for a moment. "Man alive, I miss home. Really I do."

Hans asked, "Are you having turkey?"

"What do you think I am? Rich?" Benito countered. "The price is ridiculous. They're imported from Spain. Only reason Spain has them is because someone brought them back from Mexico. Maggie O'Reilly had some young toms she sold us at the Spanish import price—and I mean to tell you she was smiling when she did it, too.

"We used to sell it retail at a dollar, dollar ten per dressed pound. If nothing happens to her layers, Maggie will die rich because she let her little girl breed turkeys for a 4H project. I hear a lot of people went hunting this week, but I don't think there were all that many wild turkeys to begin with."

Hans was thinking Benito was whining rather a lot for someone who had such a good job and nice house. But then Benito snorted a half laugh.

"No, kid, we're having goose and dressing. Goose is fine. I can't afford turkey. I won't pay that kind of money for one and I probably won't live long enough for the price to come down."

Benito knew he was feeling sorry for himself. Heck, he was probably wallowing in self-pity, come to think of it. On the other hand, though, he certainly hadn't asked to get stuck here. Everything was different, seemed like. Food, clothes, prices. Walking all over the darned place. He missed his car. He missed the food he was used to. And he missed the old Thanksgiving celebrations.

Until someone started importing corn, Benito's wife made a white bread dressing when she baked fowl.

Benito hated it. Now she bought dried corn and ran it through the blender to get meal. Which didn't make a lot of sense to Benito, since there were millers all over the place. The fact was, she'd asked for corn thinking she was getting corn meal from the bulk counter at the store. It never crossed her mind that someone might want whole corn to make hominy so she didn't say corn meal or corn flour, as the down-timers were calling it. She was too embarrassed to take it back. Now she liked the finer meal she got out of her blender better than what the store sold. They only had cornbread on special occasions, even though it was getting cheaper now that they could import dried corn from Italy.

He missed cranberry sauce, the jellied kind, from a can. They'd only had it on Thanksgiving. He really didn't like it all that much. Most of it was thrown out every year but it just wasn't Thanksgiving dinner without it. Cranberries were just one of the many things that would never again be the way they should be.

Here he was—past retirement age and then some—working full-time and then some. It certainly wasn't what he'd expected to be doing when he was sixty-six—darn near sixty-seven.

In the first year after the Ring of Fire, when everyone was scrambling to get through the winter, he pitched in like everybody else. The government tapped an experienced meat man, Mark Burroughs, to run part of the food supply project. Someone had to cover the meat counter at Johnson's grocery store. So Benito went to work for the interim while Mark was on a short term-leave. That was over three years ago. With Mark being part owner in "Ice and Slaughter," along with being the government meat, health and safety inspector, there was no way he was ever coming back from the leave of absence. The job was Benito's for as long as he wanted it. Without a social security check, he needed the income. Which was another thing that he missed, for sure. No check. Had to get a job. No wonder that old bat, Veda Mae Haggerty was so bitter. She was in the same boat.

"I'm lucky Mark ain't ever coming back," Benito mumbled. A meat counter was about all the physical labor he wanted to handle these days. Besides, without cable TV what would he do with himself, anyway?

"What did you say, Mister Genucci?" Hans asked.

"Oh, sorry, kid. I was just thinking about how things used to be."

"It really must have been something, living up-time I mean."

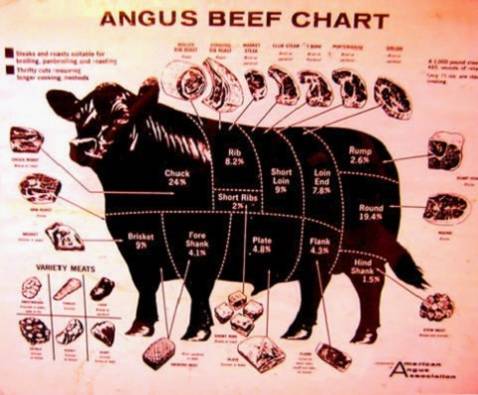

"Well, yes and no. It's kind of odd. The big difference in the job, other than the prices, is the return to paper wrapping. Cellophane and Styrofoam are gone. All the fresh meat stays iced down in the glass-front butcher's counter until it gets wrapped in paper and sent out the door."

Benito continued chatting away. "Of course, there were things you can't get at all any more, like lobster, king crab, and shrimp. And there's a long list of things you can only get once in a while. Take veal. When we have it, it's real veal. Someone's cow drops a still-born calf and the meat inspector passes it. It's not some box-raised milk-fed yearling steer, like veal used to be.

"We still get mostly beef and pork, always did. What's weird is that some of the pork is wild boar. About the only thing that hasn't been in our meat counter is dog and cat. Though, I wonder if a couple of the rabbits we sold weren't off of someone's roof, to tell the truth. We even sold squirrels once or twice.

"The quality is what it is. It isn't like you can call the supplier and raise a fuss. Hell, we should be thankful we got a supplier," Benito said. "Shoot, for that matter we should be thankful to be alive and I should be happy to have a job instead of griping about having to work."

"You would have a job, Mister Genucci. They need you."

"Thanks, kid, but I know better. I'm lucky Mark Burroughs' left to help set up a slaughter-house or I'd have your job instead of mine." They'd reached the turn to Benito's house. "Well, here's where we part company, kid. See you tomorrow. Remember, you're going with me to the slaughter house in the morning so be here at a four thirty."

The goose was good. Benito had picked out the best of the lot, after all. The stuffing was perfect. His wife had something she claimed was cranberry salad made with dried berries from Poland. They might have been cranberries—he couldn't tell the difference—but it just wasn't cranberry sauce. Still, he had to brag on it. And there was no football on the tube. The Sound of Music just was not an acceptable substitute.

He went to bed early.

The alarm went off. It was four in the morning. Again! Benito shut it off so his wife could get another three hours of sleep. His clothes were hanging on the back of the bathroom door so he didn't have to rummage around in the bedroom. At a quarter after four he was out the door.

Hans was waiting at the street corner and they took the long walk out to the slaughter-house and got there about five. What was now "Ice and Slaughter" used to be a big old barn. Now it held the cold storage along with the ice-house, the dairy and the ice cream company. They built a slaughter-house just up hill from the barn and a smoke house, downhill, off to the side.

Benito happened to be there when Slick had pitched the idea to Mark.

"Hey, Mark. I've got an old antique hand-cranked cream separator tucked away in the barn," Slick said without preamble, right in the middle of the conversation Mark was having with Benito about the meat counter at the store. "Got an old commercial ice maker stashed in there too. It'll need its Freon recharged. They got some down at the body shop . . . well, I guess it ain't really Freon, but they tell me it will work. Anyway, I was told you would have to sign off on it before they use it. I want to turn part of the barn into cold storage for milk."

"That's a mighty big barn you've got. How are you going to do turn that drafty old thing into cold storage?"

"Well, the back half of the lower level is underground. I figure I can stack hay bales three deep across the middle and fill the floor overhead with straw. That should hold a couple of semi-loads of stuff."

"Not big enough. But if we stacked the entire outside of the barn with three or four bales of straw and covered it with tarps, we can turn the whole thing into a freezer. If we can find enough straw bales. They'll cost a bundle, that's for sure."

"Think that would work? There isn't that much milk to keep cool."

Mark's eyes lit up. "No, but there's meat too. How would you like to be part owner in a slaughter-house?"

So they'd gone and done it. Somehow. Benito didn't like to think what that straw had cost. If it was straw. For all he knew, it was pine needles doing the insulating. Or even sawdust. But it worked. The second year they boxed in the outside. The loft was filled with loose straw and the ice maker set into the wall with the back side to an office to so the heat off the condenser helped keep the staff warm in the winter. Mark figured the basement would freeze and the second floor, which had its own ground level entrance at the back of the barn, would make a refrigerator. They ran the ice maker 24/7 until they had enough ice so the barn stayed cold.

Benito laughed as he and Hans trudged up the hill to the old barn. "There was some question as to whether the ice maker Slick had would make enough ice for it to work. It almost worked too well. They had to scavenge foam board out of someone's pole barn to hang on the ceiling of the lower level to keep the second floor from freezing up too."

"Herr Benito, why do you call him Slick when that is not his name?"

"Back when, he always had a scheme going. He was always trying to pull a fast one. He'd buy junk and put it in the barn and try and sell it as antiques. That's why he had the cream separator and the ice machine to begin with. Good thing it worked, I guess. Well enough that Mark's doesn't want his old job back."

Oh, there were people who griped about conflict of interest and profiteering, over Mark being part-owner of the slaughter-house. But where were they when there wasn't an ice-house? Mark, Meryle Grooms, Slick and some others got the ice- and slaughter-house up and running at their own expense when it was needed most. Benito figured they deserve what ever they got out of it. Some people can't stand seeing someone else get ahead.

"Any way, the meat grinder and the band saw from the store found their way out here. When Mark wanted them, Old Man Johnson said okay, as long as we got first dibs on meat. That's why I have to walk out here every morning to look over what they've got hanging in cold storage. That will be your job just as soon as I think you're up to it. At least we get to ride down to the store with the delivery wagon.

"Everybody knows Johnson's has the best meat in town. It don't matter anymore that they we're the smallest of the three groceries. Having the best meat will keep us in business. Though I never thought I'd see the day wild venison would be in the meat-case next to goat and sheep."

The aged quarters of the day's stock were loaded on the delivery wagon with the morning's ice while he watched and Hans helped. Then they rode to the store. "Good morning, Mister Genucci," Carl greeted him cheerfully.

Benito made a sound somewhere around a snarl that had no clear meaning. He hadn't had his coffee yet. While the ice and meat were unloaded, he'd have a free doughnut and a cup of coffee with the baker.

When the ice was in the meat counter and the meat was in the walk-in refrigerator, Benito would be ready to start the day. The ten-by-twelve cooler, which could hold about two days worth of meat, would be about half full. Anything left in-house on the third day was sold at or under cost to the relief agencies. They expected cheap meat and they got it. If there was very much meat left on the third day, Benito knew he wasn't doing his job.

The baker had a cup of coffee and his favorite roll ready for him. "Mornin', Benny."

"Mornin', Pigtails." She hadn't had pigtails since they were in grade school, when he was last called Benny by anybody but his wife. She giggled like she did every morning at the name.

She had been Johnson's last baker. When she quit to open a pizza place with her husband, the store went to having their bakery stock delivered. A couple of weeks after the Ring of Fire, Pigtails showed up one day and announced that she needed a key to get into the store at three o'clock in the morning to bake bread.

The startled manager said, "What?"

"I need a key to get into the store at three o'clock to bake bread. You sure aren't going to get any more bread deliveries and I know good and well you don't want to be here at three to let me in. So I need a key."

"Three o'clock in the morning?"

"The restaurant down on the corner wants three dozen mixed doughnuts and four loaves of bread at six o'clock. They'll go stale overnight, so I need to be here at three. We were only making a half a gross of loaf bread a day when I quit back in '78. But we're the only grocery store that still has a bakery, so we'll be selling to the other stores until they get an oven up and running."

The manager asked the whirlwind, "Who are you?"

"I'm Carlina Marcantonio. Mr. Johnson told me if he ever needed a baker again, I could have my job back. Well, you need a baker. If you don't believe me, go ask Old Man Johnson himself. Before you do, pull half of your sugar and flour off the shelf and don't restock it until you've got a supplier. We'll make more selling bread. While you're at it, pull the cinnamon and half the baking powder.

"I'm going to start cleaning the ovens."

The manager did indeed call Leroy Johnson. "Carlina? Yeah, I told her if I ever needed a baker she could have the job back. I was joking. No, you will not tell her to go home. You give her whatever she wants for as long as we've got it."

After that she ruled the roost in her corner of the store. Benito asked her once, "You've got the pizza place, why are you down here baking?"

"Benny, right after the Ring of Fire, the only thing for sure was there wouldn't be any more deliveries. I thought a job in the grocery store might be a good idea. I tried baking bread at the restaurant, but the ovens weren't big enough. I can bake more here."

The store was lucky they still had the bakery. The oven and fryer hadn't been used since she quit. There had been talk of ripping them out, but with volume slipping year by year, they didn't need the room. About the only thing ever proposed for the space was a small video arcade to siphon a few quarters out of kids' pockets while their mothers shopped. Old Man Johnson put his foot down. He remembered when an arcade meant gambling and wouldn't hear of it.

About the time Benito finished his coffee, the birds arrived from the dresser. He checked them in. It wasn't just chickens anymore. Ducks, geese, game birds—some of them quite small—all found their way onto the ice in the case. Benito didn't like seeing the song birds. They were so small and it just wasn't right. But the price they got for them and the fact that there never were any left said all there was to say on the matter.

The plucking business annoyed Benito. What that man was paying—wasn't paying was more like it—the ladies he had plucking fowl for him half the night was criminal. But they could come to work after the children were put to bed and be home by breakfast. When they slept was their problem.

By the time he had the birds checked in, all the stock left over from the day before was out on the ice and the butcher would start filling in the empty spaces behind the glass in the meat case.

By seven, the meat counter was full. By eight, Elisa, Benito's wife, arrived to handle morning sales. She was a great hand with customers. She had picked up German in nothing flat.

Elisa's working was another thing Benito didn't like about this "Brave New World." She took the job during the first frantic year. It was her only job since they married. He always insisted she had a full-time job as a mother and wife. When she announced she was going to volunteer, he objected. She told him to can it. "Everybody else is helping out. I can too." So he got her a job down at the store. The idea of some other man bossing his wife around just did not sit well with him.

Official store hours began at eight. Their wholesale customers, three eateries which served breakfast, and others, had been stopping by for doughnuts and muffins since six. There would be more commercial customers when they started preparing for lunch.

Some people who bought muffins also bought a cup of coffee after beans started arriving in Grantville. If you wanted coffee or milk or something else to go, then you brought a container. No more Styrofoam cups. No more banana muffins, either. Benito missed those.

At eight, the housewives and cooks or their helpers would start arriving, some with small children in tow. Everybody was off to work or school and the day's provisions needed to be purchased. One cook for an up-time family bought seven eggs on one day and eight on the next. She brought an old egg carton with her each day to get them home safely, except on Saturday. Then she brought two because she would be buying seventeen eggs. Benito knew the family had insisted they would buy a week's supply of food at a time, so she would not have to walk to the store each day and tote everything home in a canvas bag. It never worked out. She always forgot something or ran out or, or, or—. She was there every day and would walk each and every aisle chattering away in some strange dialect with three other ladies. Elisa told him, "It's her way of getting out of the house to socialize. Women and shopping, Benny, some things are always the same."

Elisa worked from eight to twelve each day, chatting with the customers while they picked up a quarter pound of bacon, and "How is Tomas' gout this morning." A half pound of ground sausage, "Is your cough any better?" A roast for dinner, "I see you got down to the beauty shop for a hair cut." After the mad rush to survive was over Elisa kept working.

Benito told her, "I think you ought to quit."

"Forget it," she told him. "I like working."

Friday was fish day. There was more ice and less meat on the wagon on Fridays.

"Mr. Genucci, why do we not stock more fish? We sell out every Friday around noon, it is not like other days when there is fish to closing that we have to sell cheap the next day," the butcher's helper asked.

"Kid, we put out all the fresh fish we can get. The customers prefer it. Salted, dried, smoked or pickled fish will do, but they want fresh fish if they can get it. There's only so much available and we split it up even with the other grocers. At first the catfish only sold when there was nothing else. Now it's the first to go."

Along with carp, catfish did very well in the fish ponds that sprang up during the first frantic year. They were the bulk of the Friday fish. The rest of the week got whatever the fishermen brought in. The preserved fish arrived in barrels and were sold with the bulk food, so they weren't Benito's worry.

The birds arrived, so Benito checked them in. Then he told the deliveryman, "You tell that cheapskate boss of yours I only want a half order on Fridays. We've been through this before. He keeps trying to creep the Friday count back up. If I've got more than half a dozen birds left over in the morning, you'll be taking some back with you."

"The boss won't like that."

"So tell him to quit oversupplying me."

By then the fish were out on the ice along with a selection of red meat and the fowl. Benito looked the counter over and then wandered over to the barrel aisle to have the same conversation with the bulk food manager he had every Friday.

As the shelves emptied out, half of them were taken down and put in storage. Now there was a row of barrels and crocks and bags behind a counter. You told a clerk what you wanted and the clerk scooped it out, weighed, measured or counted it, then poured it into your container and a tab was taken to the cashier. Milk, cream, butter, cheeses, beer, wine, whiskey, cabbage and turnip sauerkraut, a variety of flours, along with Grantville Extra Fine Flour that the up-timers wanted, expensive sugar and spices, rolled oats (a novelty that quickly became a favorite), fish, anything pickled, anything dried including various beans and several types of whole grains were all to be had in bulk. Prepackaged lots were uncommon, as were prepared foods, for the most part. Oddly, ice cream, which was mostly sold by the scoop, was attached to the bakery.

"Well, are you ready for the run on fish? We've bought everything we can get and it will be gone by ten," Benito said.

"Not to worry. We've got plenty. Actually, that new barrel of New England cod is really looking good. I hope the next one we open measures up. The pickled herring is pickled, the anchovies are salted and I'm not sure what that smoked fish from Finland is, but I want another barrel of it."

"Well, if you run out, you've always got beans."

"I don't know, Benito. We're down to only eight different kinds right now."

"Did you get me that peanut butter I asked for?"

"I keep putting in the order, but it never seems to come in."

"That's too bad," Benito said. Then he wandered over to chat with the produce man.

Fresh produce hardly changed at all. What was available was completely seasonal. Not to mention, produce that would have been thrown out up-time was being sold and for a good price. There was nothing better to be had. By this time of the year, all he had were potatoes, apples, pears, onions and some winter squash. The last of the carrots were looking pretty sad. All of it came from the cold room at Ice and Slaughter.

Benito and the produce man walked the aisles just to see what was there. The shelves had a growing variety of products. Benito pointed to an oddity.

"Look at the price. I bet all three bottles go to the same buyer." Anything in an up-time package disappeared in short order at high prices. Out-of-towners would buy them either as souvenirs or for resale.

More and more new things were being sold off the shelf. Surplus from kitchen gardens could be frozen, dried or pickled and sold to the store or, just as likely, left for credit. Benito always grumped at the pickled vegetables when Elisa served them at home. They put his teeth on edge.

Delbert and Benito walked past all kinds of odds and ends on the shelves. Most of it was related to food. The store's buyer drew the line at clothes and such. There was a whole aisle of pots, pans, dishes and flatware. It used to be all used stuff. It now included new paper plates and napkins at an outrageous price which did not stop out-of-towners from buying them. A restaurant in town had them made up and the paper-maker sold what the eatery wouldn't buy to the grocery store.

Delbert said, "Mrs. Freeman's old ceramics hobby really took off." He was looking at her line of china.

"Are we still selling the tinker's wares to the other stores?"

A tinker was happy to sell them his wares, as long as they would take everything he made so he didn't have to hawk them at the market down at the fair grounds. The store's buyer had to sell some of it to other stores at first.

"Not since he started putting a Grantville trademark on his product. And even after they raised the price, we can't keep it on the shelves. The soap-maker ought to try that."

"Why not? It's working for the tinker and the broom-maker."

The "Made in Grantville" trademark sold almost as well as things from up-time, even if they didn't bring quite as much.

"I don't know how much longer we'll carry the pots and pans, though. I think the Wish Book is going to start cutting into our sales."

"Well, I guess the tinker can still make a living by making repairs. But I bet the catalog runs him out of business one of these days."

It crossed Benito's mind that Johnson's Grocery had a lot in common with the old general store he could barely remember from his childhood. It had a way of making him feel young and old at the same time. He knew he should be thankful to have a job he could handle at his age. But, when he thought of it, the quote from Eeyore the Donkey always seemed to come to mind: "The Good Lord gave us tails to keep off the flies. I'd just as soon have no tail and no flies."

Thanksgiving was past. Benito knew he had a lot to be thankful for. Still, the truth be told, he'd swap it all for a can of cranberry sauce and a bowl game on TV.