Something didn't fit, and it looked important.

Else Berding had gone to the break room for a cup of coffee. She came out to see Jennifer Hanson in the hallway, carrying on a conversation through a ham walkie-talkie. It was a little bit of a thing, no more than four inches high, with an eight-inch flex antenna sticking out the top.

"Far as I could tell from the phone message slip, it sounded like he was talking about some old CW transmitter that he hasn't used in years. Nothing high powered, but for sure a way to get on the air."

The other station came back. "That sounds pretty good, Jennifer. You think we could afford it for the club station?"

"Good chance of it. I'll be seeing him tonight, and we'll find out one way or the other."

"Okay, and if it don't work out, maybe we can build something up from junk box parts. Well, I've got a class in a few minutes, so I'll sign off with you now. W1PK, W8AAG."

"See you later. W8AAG, W1PK."

Else stopped dead. "A class? I've heard you talk to him before, but I thought he was someone here in the plant. Where is he?"

"Oh, that's Rolf Kreuzer. He's a junior at the high school. We've been scrounging around for some gear to put together a club station over there. The kids need it, if they're going to actually do anything with ham radio."

Else looked confused. "He's at the high school? What band were you using?"

"Two meters."

"I thought everybody said all those high frequency bands are line-of-sight, until the sky wave skip finally comes back."

"Well, it pretty much is."

"But, there's a hill between here and the high school! There isn't a line of sight between here and there."

"It's pretty close to one, though."

"Pretty close isn't the same thing at all. There has to be some other physical effect involved. Does Professor Müller know about this?"

Without waiting for an answer, Else charged off to her boss's office.

John Grover was just getting up to leave. Müller waved her in.

"Conrad, you asked us all to report any unexpected observations that have anything to do with the project . . ." Grover turned back, listening alertly.

Else described what she'd just seen. " . . . so you see, line-of-sight can't explain that. There must be another physical effect, to make that happen. It might be something we can use." Else stopped. She saw how Grover was standing. He was no longer poised like some prospector looking at gold dust on the bottom of a creek. Now he was leaning back against the door frame, and smiling slightly, like—a teacher listening to a favorite student? "You know about this." It was a statement, not a question.

"Uh, yeah, we do. There are several effects that can make a radio wave go around terrain obstructions. The army is making good use of them, too. Thing is, we don't think the Ostenders and the Austrians have figured it out yet, and we want to keep it that way as long as we can. So keep it quiet outside our group, okay?"

"Oh. All right. Well, I'd better go back to my desk, then."

By this time Jennifer had caught up, and they walked down the hall together. Else asked, "Did I do something foolish?"

"No, you did what they asked you to. I was about to tell you, but I didn't get my mouth open fast enough. I'm sooorrry. Forgive me?"

Else burst out laughing at the sight of a thirty-four-year-old wife and mother, pouting like a penitent little girl.

After they left, Grover stayed a moment longer. He shook his head. "Damn, that was brilliant."

Müller looked up at him. "Oh, yes. If we had two or three more like her, this project would move faster."

"You know why she spotted that so quick? Chuck Fielder and the rest of them teach their students to think like scientists."

The invitation to an interview at General Electronics had come as a complete surprise. John Grover had been honest, and so had Else.

"You understand, Mr. Grover, I've finished only about half the courses I planned. And even that is from study groups, not school courses."

"Yes, I do understand that, Fraulein Berding. But Conrad and I think the ones you've finished are the ones you need to do this job. Your last study group adviser thinks you have what it takes to learn the material.

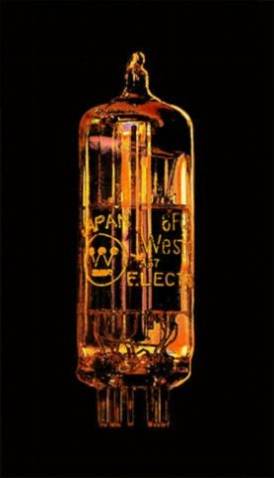

"Of course, it would be better for you and us if you had the rest of the courses, and an experienced electronics engineer to work with on the job. But not much about the Ring of Fire was fair. There isn't anybody like that. What we have is a really good collection of books on vacuum tube theory in Gayle Mason's library. What we don't have is somebody who can put them to work. You're the first person to come in here who has the math and physics to really understand the electrical insides of a tube."

"Wouldn't it work better if I went further with physics before taking up something like this?"

"Probably. But let me lay out the situation. VOA runs on tubes, and they don't last forever. We only have a few. When the last ones burn out, we're off the air unless we figure out how to repair them by then. Most of the long-range transmitters for military and diplomatic radio are in the same situation, and some of them don't have any spares at all. And then there's a lot of transistor gear the army is using. They don't need tubes, but when something breaks, we don't have parts to fix them with. Before too many of them wear out or break down, we need to be building replacements. And once we run out of up-time parts we can salvage, that takes tubes. We're already behind schedule. You can imagine what could happen if we let too much more time slip away. Battles can be won or lost in seconds. Better something they can use in time than a perfect solution too late."

"I see. I'm still not sure. Could I look at these books, and see how well I can understand them?"

"Sure. I can't let them out of the building, but I'll take you up to the library. And there's one other thing. You won't be stuck completely on your own. You know Charnock Fielder? He has a lot of other demands on his time, but he does some consulting for us. He can help you figure things out if something doesn't make sense."

"That might make a great difference. I had one of his physics classes. He explains things very well."

The next day Else was back.

"Mr. Grover, I've thought very hard about what you said. I probably wouldn't be alive if the Emergency Committee hadn't taken me in three years ago. They offered me citizenship and school. Now, it seems, it's time to pay back. I believe I can learn what is in those books. I will join you and do my best." She reached her hand across the desk to shake. She looked very serious and very young at that moment.

That night she prayed. Lord, help me do what they ask of me. Research engineer . . .

She lay down to sleep, wondering whether she'd ever hear anything of her family again.

Else had studied hard before, but not like this. But the principles were starting to make sense. The vacuum wasn't quite good enough yet, and it would be a while before the materials people could give her group what they'd need to build a test model, but they had some idea of what they'd be able to get within the next few months. Meanwhile, she was working out a couple of trial designs on paper.

Late in the morning Else went out to the lab. She called across the room to Heinz Bennemann, "I need to study the pieces of that dead tube you took apart some more. Where do you keep them?"

"Third shelf in the cabinet, in the little red felt-lined box."

"Felt-lined, is it? Still the fine jeweler?"

"I was only a jeweler's apprentice. Now they call me a general technician. It means I'll never be done learning things. There's no such thing as mastering this trade."

"No? What do you think a research engineer is?" Else took the box over to a bench where there was a microscope and a precision mechanical stage, and settled down on a tall wooden stool. A flapping belt drive under another bench caught her eye.

"Heinz, shouldn't there be a guard over that belt?"

"We'll put it on when we're done. You know Marius Fleischer, here? No? He's a mechanic from the vacuum group. He just brought over a better roughing pump, and we're trying it out."

Fleischer put in, "It seems to need a few adjustments yet."

He and Heinz turned back to the assembly drawing.

Marieke Kettering was a good-natured woman in her mid-forties, with the gift of maintaining her good nature regardless of what kind of deadline pressure and turmoil were erupting around her. Being in charge of personnel and purchasing for both VOA and GE, she needed it. She heard the front door close, and then footsteps coming to her office.

"Gertrud! What a pleasant surprise! What brings you here? Sit."

"Oh, Marieke, we were just passing by. We're going into town for a little shopping."

"And who is this fine fellow in your lap?"

"This is my little nephew Erwin Spiegelhoff. Erwin, say hello to Frau Kettering."

"Gwathm!" exclaimed Erwin, with the sunniest of smiles.

Gertrud continued, "So, have you seen the new Brillo play yet?"

"No, but I want to. My cousin says it's insane, with them saying one thing in English, and then not exactly the same thing in German."

"Well, why don't I see if I can get us some tickets? Do you think Hermann would want to come too?"

Erwin slipped off his aunt's lap and started playing with his wooden duck on the floor. After a few moments of conversation, Gertrud noticed the silence. "Erwin?" She looked around the office. No Erwin. She stepped out into the hall, just in time to see the toddler disappearing through a doorway.

"Nein, Erwin! Komm zu Tante!"

Erwin didn't feel like coming to Auntie just then. What he heard was the interesting rhythmic blup-blup-blup coming from under a bench. He saw the shiny things going round and round, and the long thin black thing bouncing energetically up and down between them. He made a beeline for the vacuum pump.

Else was just taking a quick stretch. Something was moving down low . . .

"Heinz! Look out!" She pointed at the little boy, and scrambled off the tall wooden stool, sending it flying.

Heinz dove for the floor, trying to get between the child and the moving parts. Else flew toward the spot. They got in each other's way for just a moment. Just as Heinz got an arm in front of the boy and started to push him back, and Else got one hand on the edge of the bench to brace herself and the other hand on the boy's shoulder, he grabbed the drive belt. It whipped his left hand under the idler wheel.

Marius yanked the power cord out of the wall and started cranking the roughing valve shut to keep the diffusion pump from coming up to air.

It was never clear afterward whether the child had grabbed at the test leads dangling over the edge of the bench, or whether Heinz snagged them with his foot as he hit the floor. Else saw something start to slide toward the edge of the bench, and tried to stick out a foot to cushion its fall. There was no time. It hit the floor with a sickening crack.

Marieke and another woman came running full-tilt into the lab just as the boy let out his first deafening scream. Else cradled the child in her arms, blood on them both.

"Erwin," the strange woman cried. "Erwin!"

Else called, "Frau Kettering! The first aid kit!" She held Erwin as still as she could, while Heinz took a fast look at the injury and got a bandage on it to control the bleeding.

Heinz looked up with a sober expression. "It doesn't look good. His hand is all cut up. He needs the hospital."

Marieke swallowed. "I'll get the ambulance." She picked up the telephone.

The other woman took Erwin in her lap and wrapped her arms around him. "Erwin, Erwin, it will be all right. There are good people coming to make it stop hurting."

Erwin screamed.

After the ambulance left, Else and Heinz finally had a chance to look at what had hit the floor. It was Gayle Mason's Simpson 260 multimeter. The case was smashed to fragments, the glass had a crack all the way across, and the needle was bent. Heinz delicately picked the pieces off the floor to prevent any more damage, and collected them in a box. About then, John Grover arrived in the lab to see Else glumly sizing up the remains. She showed him.

"It's a mess, all right. I'm a lot more concerned about that little kid, though. We've got other meters in the lab."

"Yes, John, but this is the only one with a calibration sticker from up-time. We've been using it to standardize all the other electrical measurements."

"Oh, boy. Well, we'd try to fix it anyway, but it looks like we have a real incentive here, huh? Heinz, you're about the best tech here for fine work. What do you think?"

Heinz shrugged. "I haven't worked on meters before. This is different from the other little parts I've made. I wouldn't like to take a chance with this, if there's anyone else in town who knows more about these things."

"Well, there's always AEW. They make meters. Fine, let's see what they think."

The accident investigation took up most of the afternoon. Jacob Cokeroff, the head of the vacuum group, doubled as the company's safety officer. He had barely started interviewing everybody involved when the city fire marshal showed up. Between the interruptions and the staff's state of mind, there wasn't a lot of useful work done for the rest of the day.

Late in the afternoon Cokeroff and the marshal were wrapping up in John Grover's office, and discussing what would go in the report. The phone rang.

"That was Marieke. She just heard from the hospital. Erwin is out of surgery. It's not great, but it could have been a lot worse. They had to pin two bones back together, and he's lost one joint off his middle finger. There'll be some scarring. Outside of that, they think he'll be able to use the hand all right."

Cokeroff nodded. "We should be thankful."

"Oh, yeah. I was really worried. All the effort we put into safety, and this comes out of the blue. We don't want anything like this to happen again. So, recommendations . . ."

The next morning, Frau Kettering started working through a handful of signed requisitions. Her first visitor of the day was a carpenter.

"Right here, in the hall, between the offices and the workshops—I'll show you. A divided door, with fire exit hardware, locked on the outside. All right? How much, and how soon can you put it in?"

Next, she called in a sign painter.

"We need a sign on each of the doors going into the lab and shop area. 'Danger, Escort Required,' in big black letters on a yellow background. German and English. Latin too, I think."

Then things got harder. She called the sales department at American Electric Works. "Hello, I understand you make meters. We have a damaged multimeter from up-time that needs repair. Can you help with that?"

"What exactly is that? Something we make?"

"No, it's from up-time. It's irreplaceable, and it was calibrated. We need it for a defense project. My engineers think you're the only company that would know anything about it."

The president of the company came on the line.

"This is Landon Reardon. What can I do for you?"

"This is Marieke Kettering at General Electronics. We have a damaged Simpson 260 multimeter. It was broken in a fall. I understand you make meters, and I wonder if your company could repair it."

"A 260? Yeah, I know what that is. I used one when I worked at the power plant. How bad is it?"

"Well, the case is in pieces, and some of the parts inside are bent. They're not sure what else might be wrong."

"Oh, brother." He sighed. "I can't promise anything, but send it over with the manual. I'll ask the guys to go over it, and we'll let you know whether there's anything we can do."

The man who sometimes called himself Johann Schmidt was intrigued. He'd passed this building before. Those locks on the doors look new. Yes, the metal isn't weathered. Nobody to be allowed inside without being watched? Danger? What a naive ruse! There are secrets behind those doors. Obviously. Perhaps useful ones.

He continued to observe the building at intervals, but now he came no closer than a block, and never faced it directly. His patience was rewarded after three days. Several people left work, and one of them didn't show the alertness and purposeful stride of someone in charge. This man was dressed a little more cheaply than some of the others. "Schmidt" followed, half a block behind and on the other side of the street. The man went into a drinking establishment, a nondescript working man's place. "Schmidt" went in after a few minutes. He found a seat across the room, ordered a beer, and sat down to sip it, speaking to nobody but the barman. He continued to observe, without looking directly. After a while, the plain-looking man joined a card game at a table. This looks interesting. Yes, an indifferent player. The play of expression on his face as he lost very small sums showed it. Here's a man who can use a little money.

The next night, "Schmidt" arrived first. The room was fairly crowded, but there were two neighboring unoccupied places at the bar. He took one of them and waited.

The pace at GE was back to normal. Normal meant frantic. Else was constantly dealing with things she'd never studied, reading up herself, sending queries to Father Nicholas and the other researchers, answering questions, supervising experiments, taking measurements herself, or conferring with specialists in other groups.

One time it would be Heinz asking, "Else, do these results make any sense to you?"

Cokeroff wondered, "There's a kind of high vacuum gauge that looks something like a tube. Do you know anything about that? Could we make it?"

Another time: "Else, do you think we'd be better off modeling the electric fields around the control grid by computer, or in an old-fashioned electrolytic tank?"

"I'm not sure, Conrad, I'll give that some thought and get back to you. Maybe they'd both have a place. Do you know a good computer programmer? But maybe an analytic solution might be possible."

At least she didn't have to worry about vacuum-tight electrical feedthroughs for the tube bases. That was mostly mechanical engineering, and Conrad Müller was working on it. Even so, it was hard to keep up with everything.

One morning she planned to write a technical paper on receiver tuning capacitors. She'd solved the math the day before, and now she was going to reduce it to a procedure an electronic designer could manage with only high school math. She reached for her notebook without looking, and felt—nothing. She looked up. There it was on her desk, but a foot to the left of where she was certain she'd left it the night before. Conrad came in while the befuddled look was still on her face.

"You look like something's the matter, Else."

"Nothing, really. I just misremembered where this was. I almost always put it over here. I was sure . . ."

"You do look tired. Are you getting enough sleep?"

"Well, I was up late last night studying. There's so much to understand, to be ready to move right away when we have a good vacuum."

"Ah. One thing I learned when I was a student was not to burn the candle at both ends. What am I saying? These days I study as much as I ever did. If you're too tired to think, you can't accomplish anything. Besides, there are dangerous things here. You don't want to make some bad mistake."

"It's hard, sometimes, but there are so many people depending on us."

"You won't do them any good if you have to do work over because you were too tired to do it right the first time, or you get yourself hurt. Learn what your limits are and respect them. Workers must get enough rest to stay alert." He gave her a little smile, and left her to what she was doing.

The tube group found workarounds for the missing meter, but it was tedious and inefficient. Finally, the wizards at AEW pulled off a small, expensive miracle.

Heinz showed it off to the group. "See here? Somebody in the cabinet maker's shop at Kudzu Werke made this oak case to replace the broken one. And there's a padded leather outer cover. I might tie it to the bench the next time we use it, though. You can hardly tell that the needle was ever bent. They said there was a wire torn off a range resistor inside, and fixing that was the most delicate repair."

Conrad asked, "So it's good as new?"

"Well, not quite. There was some damage to the jeweled pivots they couldn't do anything about. We have to tap it lightly with a finger to get the needle to settle to the final position. But I've compared it with readings from some other meters before it fell, and it doesn't seem to have changed."

Heinz went back to putting together an experimental vacuum gauge he'd been working on the night before. He went to pick up his little Phillips screwdriver, but it wasn't in sight. Maybe somebody borrowed it? He looked at the nearby benches, but didn't see it there. Then he saw it from two benches away. It was behind his toolbox. Hm. Must have rolled there somehow.

Else kept tearing away at the theoretical work. It wasn't always tubes. It would have done GE little good to develop tubes if they weren't ready to make all the other parts for receivers and transmitters.

So it might be, "Else, Jennifer has taken apart an old coupling capacitor. It's made of tinfoil, paper, and beeswax. That, we could make, if we substitute copper foil for the tin. Could you work out the design equations, and help the manufacturing engineer figure out what kind of paper to use?"

On another day it was, "Else, Jennifer is asking for help. The Radio Amateur's Handbook has equations and charts for the inductance of an air-wound coil, but there's nothing about sizing it according to the power level. Can you come up with some recommendations? The techs can run any tests you need to confirm it."

Or Grover asking, "Else, we have a new high school graduate coming in tomorrow to apply for an electronic designer job. Would you help us interview him?"

Some nights they'd go up to the comm station to pick Gayle Mason's brains. John Grover was a fast hand at the key, but conversing in Morse code was slow going compared to talking face-to-face, especially on the nights they had to relay through Amsterdam. Still, Gayle saved them a lot of wasted effort.

While all that was going on, Else continued studying more advanced math. She could see that she was going to need the convenient but conceptually challenging theory of Laplace transforms even to understand the cookbook manuals, once she started in on the receiving filters that picked out just one incoming signal. So, she was currently participating in a group studying differential equations. It got together a couple of times a week. There was just so much to learn, and so little time before it would all be needed.

The family she boarded with had three small boys. She didn't exactly mind the noise, but sometimes it was too much even with her door closed, when she was trying to grasp really difficult material. Besides, her office was a comfortable place to study, and she could always get a cup of coffee from the break room. It was a much-appreciated benefit the company provided.

One night she was working through a textbook problem, with only her desk light turned on. The floor creaked briefly. Somebody in the lab? She looked out, but there was nobody there. Maybe it was the building settling after the heat of the day.

John Grover happened by while a couple of techs were joking about the haunted laboratory. "Oh, yeah, my dad used to tell stories like that. He worked on bombers in England during the Second World War. Stuff would go haywire for no obvious reason. They blamed it on the gremlins."

"What are gremlins?"

"Little people you never see. Kind of like fairies."

Jacob Cokeroff growled, "Gut, but we are in Germany, not England. If we are to have imaginary friends, they should be called kobolds."

"Sure, Jacob. On another subject, how's the vacuum looking?"

"Almost good enough to do something useful with. I have hopes of something usable for lab work in another week or two."

"Glad to hear it. The materials folks have been poking into some pretty strange places and come up with little bits of scrap to try out. Thanks to Father Nick for the clues again."

The experimental work was about to start.

Else decided she needed a change from her difficult math studies. She decided to attempt something not quite so demanding for the moment. She could see that with the stage the project had reached, she'd need to operate transmitters herself before very long. So she decided to get her license now, rather than later. After two evenings with the study guides, she felt ready. And so, one Saturday morning, she showed up for the test session put on by the Grantville Amateur Radio Club's volunteer examiners. Typically for Else, she passed on the first try. They issued her a ham license and a station call sign—W8AAQ. Then they invited her to the club meetings.

On the last Friday afternoon before Labor Day, there was a set of cathode coating samples Else wanted to test herself. Near the end of the day she finished taking the data, and shut everything down but the vacuum pump. The tech who'd stayed as safety observer while she had the high voltage on went to finish up some other work. Else wanted to think about the results over the long weekend, so she took her notebook along in her canvas bag, along with some reference material.

After she left the building, she happened to glance back. What on earth? I'm sure I turned off the bench light. She mentally cringed. If I hadn't looked back, three days of that bulb's life would have been used up for no reason.

Else stepped into the lab, and stopped. What she saw made absolutely no sense. Somebody was sitting in front of her bench, writing on a piece of paper. She could see by the warning lights that the power was on. Why is somebody else repeating my experiment? It's that mechanic from the vacuum group—why would they be interested in this? Why would Conrad let somebody else run my setup, and not tell me? And there's nobody else here, this is an awful safety violation.

She spoke hesitantly, just loud enough to be heard over the noise from the vacuum pump. "Marius? What are you doing?"

The color drained out of Marius Fleischer's face, and he came up off the stool with a squawk, unbalancing it and knocking it over. He tried to dodge around Else to get out the door, but one foot caught in the stool's rungs, and it pulled him to one side.

Else saw him coming straight at her. She took a half-step back to get a firmer stance, and reached out to fend him off. The shove unbalanced him further. He shot out his hand to one side for support. It came down on the power supply.

"Conrad! Heinz! Anybody! Help!" Else shouted.

When Conrad Müller and two techs came running into the lab half a minute later, they found Else on her knees, one hand on top of the other, pumping rhythmically on the center of Fleischer's chest.

Müller called, "Heinz! Call for an ambulance! Electric shock." He knelt beside Else and said, "I'll take over the CPR. Turn off anything dangerous before the ambulance gets here."

Between emergency treatment and getting the lab into a safe condition, things were busy and confused for the next few minutes. After the ambulance crew got through with the defibrillator and it looked like the patient would probably live, Conrad finally had time to ask, "What happened?"

Else shook her head. "He was re-running the experiment I just finished. Did you tell him he could do that?"

"No, of course not. There was nobody else here? He didn't want anybody else to know. Now, why? He wasn't taking that data for our benefit . . ."

Heinz put in, "Kobolds."

"What?"

"All those times things weren't where they were supposed to be. Maybe some of the time it was us being absent-minded. Maybe some of the time it was him looking at stuff, and not remembering just where it was before he picked it up."

Conrad called John Grover. Grover called army intelligence. Two agents had a long discussion with Marius Fleischer.

"Fleischer talked, no problem," the intelligence officer said. "He didn't even try to clam up. Unfortunately, he doesn't know anything useful. He has no idea who he was working for. It was dead drops in both directions, money and instructions in, reports out. The only time he met anybody face-to-face was when he was recruited, and he didn't get a name—which would have been fake anyway. The guy spoke perfect high German, like some local burgher. Maybe he was a local burgher, or had been."

Grover sat back in his chair. "Wow. Tradecraft like that? Sounds like some Russian faction."

"Not necessarily. Could just as easily be somebody who read a bunch of spy novels. Maybe a foreign spy, maybe just a free-lancer selling secrets to anybody who'll pay."

"You catch anybody else?"

"No. By the time we got to talk to him, he was overdue to shift the position of a half-brick underneath a mailbox someplace. Whoever was servicing his drop quit doing it. So. What did Fleischer get?"

"Well, the general scope of what we're working on. Building all the radio gear we can with the parts we can find, developing tubes and new components, and all our vacuum work right up to the minute. Writing up the vacuum work was part of his job—he didn't even have to hide that. We've been asking everybody about their kobold experiences, and it looks like he was poking into just about everything around here that gives clues to what we're doing and how we're doing it—if we're not all being paranoid now. If he got some of Jen's antenna designs, a good analyst might be able to figure out what we're really doing with radio, but that cat got out of the bag, anyway. One big thing he didn't get is a workable formulation for a good cathode coating and a process to make it, because we don't have that yet ourselves. And we don't have any complete tube designs. But it looks like we're getting close, and he probably reported that."

"Kind of careless, wasn't he? Weird, sitting down and running that lab test. I don't see why he took the chance."

"Probably because Else took her notebook home that night, so he couldn't just copy the data. He must have thought there was something important in those results. There wasn't. Well, I doubt anybody else can put together the industrial base to use what he got for a long time."

The officer's face grew grim. "Don't be too sure. Those machine tool factories have been running three shifts for a couple years now, and not everything they've shipped has turned up where it was supposed to go. There's an industrial buildup starting somewhere. Still, you stopped him before he got the real goods."

The only thing to do was keep the work going as fast as they could sustain it.

They had to order parts to repair some of the equipment Fleischer had dragged to the floor when he fell. At least this time, it was all down-time equipment they'd built themselves. It took four days to get everything working again.

Meanwhile, the materials group delivered a new batch of samples. Else hooked up the test gear. "Let's see what they've given us today. Maybe we'll be lucky." She turned up the voltage while Conrad and Heinz watched over her shoulder. Ten minutes later, the numbers in her notebook told the story. "There's emission, Conrad, but not enough to be useful for a tube. We aren't there yet."

"Well, you know what they say. Any experiment that produces data is successful."

"I keep telling myself that," she said with a rueful smile. "I'd better go show them these results."

Heinz interjected, "This is much better than last time, though. It feels like we're close."

It took two more batches of samples, and three more weeks. This time one of the samples was twenty times better than the rest. Still nothing like the best up-time cathode coatings, but marginally usable. Else said the magic words: "Conrad, I think it's good enough. Just barely, but good enough. With this, I can design an amplifier tube."

Müller straightened up and smiled. "How long, do you think?"

"Probably a day or two. I'll do the calculations, and give Heinz the drawings for the parts. Then we'll see."

Things happened fast after that. Near the end of the week, Else and Heinz were mounting the delicate assembly in the vacuum chamber and starting the pump-down. The next morning it was baked out and ready. Else finished connecting the test setup. She turned to Heinz with a nervous smile. "You'd better check it too. We've come so far, I don't want to risk burning something out now."

He started comparing the connections on the bench against the diagram in the notebook, lead by lead. Finally, Heinz said, "I agree, Else. It's correct."

Else looked at the bench with a little frown. There was so much test equipment spread across it, that there was no room for her notebook. She settled herself on a lab stool, with the notebook in her lap. "Heinz, you'll have to work the knobs this time. To start with, load resistance to maximum. Grid voltage . . ."

He began stepping the voltage and load controls through the test conditions as she called them out, while she took down the meter readings. By the time they were halfway through, it was obvious. Müller was already on the phone to John Grover. In some mysterious way, word started to spread through the building, and heads began popping out of offices and shops. Finally, the test run was complete. Müller took one long look at the columns of numbers. Then he stepped out into the corridor grinning like a seven-year-old on his birthday, and held out both hands above his head thumbs-up. Cheers erupted.

When he came back into the lab, there was a serene look on Else's face that he'd never seen before. She was gazing out the window at the brilliant reds and golds of the sugar maple outside. One arm was draped casually along the edge of the bench, and the other rested on the notebook in her lap, the pen still in her hand. She looked up at him, and spoke quietly. "Now we know, Conrad. We can do this."

Heinz was still shutting down the power supplies. Without looking up, he said, "Now we got to figure out how to turn this into something we can put in a glass shell and seal it up. We still got work to do."

The push was on for the payoff. The former jewelers and glassblowers were working the kinks out of their new techniques, getting ready to cut open the precious burned-out up-time tubes. The test samples from the materials group kept getting better. Else was continually revising her repair part designs and performance estimates.

The engineering contingent was starting to look ahead to pilot production tooling for the new tube designs. Conrad and Else walked down to Marcantonio's machine shop one afternoon, to have a brainstorming session with the machine designers there.

"Well, what do you think, Else? Is the job a little less intimidating now?"

"Oh, I still have days when I wonder whether I know what I'm doing. But, yes, this is the most fascinating thing I can imagine. I've decided. This is my career. There's a lot of studying left before I can finish the curriculum, but I intend to be an electronics engineer for real. What about you, Conrad? It still feels strange to be calling a full professor 'Conrad.' Are you going back to teaching?"

"When the right time comes, I will. Yes."

"So. We'll all miss you, when you do."

"Maybe not. I might be teaching right here. There's starting to be a little loose talk of a college, for engineers, like us. Maybe we'll get you teaching, too. I hear you've been doing some lecturing."

She blushed. "What? Those little talks at the radio club? They're nothing. Nothing at all."

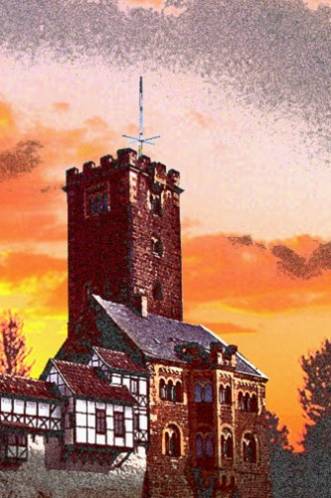

Toward the end of the year the power lines reached Schwarza Castle. Five months later the Schwarza Castle two-meter repeater went on the air. It was the most ramshackle collection of obsolete junk imaginable. Higher hills a few miles away limited its useful coverage. But it worked. Rolf Kreuzer spearheaded the effort, and the automatic Morse code identifier carried his call sign. And Rolf made his own career plans and signed up for calculus in the spring term. But that's another story.