The lookout squinted. In the east, a horizon-hugging bank of clouds glowed red, heralding the imminent sunrise. In the west, the sky was a deep azure, with only a few stars still glimmering. Below his perch was a dark skeleton of masts and spars.

He turned to the north. He saw naught but water and air, but he knew that somewhere beyond the horizon lay the shimmering sands of the Costa de la Luz, the Coast of Light.

At the periphery of his vision, a flash of white caught his eye. It was gone before he could snap his head around. A phantasm? A wave breaking? He wasn't sure. There it was again!

"A sail, a sail!" he cried. "East northeast. Hull down." Whether the sighting meant profit, or peril, or a measure of each, he knew not.

By now, the lookout had a sense of its movement. "Heading west north west."

On the deck far below, Captain Jan Janszoon smiled. "It appears that this cruise won't be boring, after all." He pulled out a spyglass—it had been taken off a Venetian prize, and was worth its weight in gold—and made his own observations.

The mystery ship was maintaining its westward course, edging closer to Janszoon. It didn't turn, either to flee, or to reach Janszoon more quickly. Clearly, it hadn't detected their presence. No surprise, that; Janszoon's vessel had furled its sails at the first hint of dawn.

Janszoon studied the visitor. "Merchanter," he announced at last. "A big one." The men whooped.

"Set sail, just the lower courses for the nonce." That would make it harder for the prey to spot them, but they would also make less speed. "Vargas, we head north." The helmsman nodded. That would give them fast legs, and, given their windward position, it would be difficult for their prey to escape to the west. "Oh, and Pieter, raise the Spanish flag. Who knows? They might be idiots and come ask us for news."

Time passed; the ships converged. The merchanter seemed to sail well, close-hauled, which implied she had a full load. More good news.

At last, with the range down to perhaps ten miles, Janszoon saw a reaction. The trader put on every scrap of canvas it had, even its studding sails. Plainly, it didn't think he was a countryman, come for a friendly chat. What a pity.

Putting on that much sail was dangerous, too. The strong southwesterly wind of the Gulf of Cadiz, the

vendavale, could knock down a crowded mast.

Clearly, the merchant hoped he could escape to the open sea. Janszoon would not allow it. "Make fighting sail," he commanded. "And lay us four points to starboard." That wasn't the quite the shortest interception course, but it would make it more difficult for the prey to clap on the wind and get on Janszoon's weather side, where it might more readily give him the slip.

Soon they were close enough to hail it. "From whence came ye, and where are you bound?"

"From Venice, bound for Cadiz. And you?"

Janszoon was delighted by the answer. The target was clearly a Spaniard. "From the Sea, and bound for Hell!" he shouted. "Pieter, show them who we are."

Pieter grinned. He knew the drill. The false flag came down, and two new ones went up. The first was the standard of the Prince of Orange, the leader of the Dutch people in the fight against the Spanish. The second would give them even greater pause.

The feared emblem of the Sallee Rovers, a gold man-in-the-moon on a red background, soon fluttered above the head of Jan Janszoon . . . Murad Reis, the infamous Renegado. On the deck of his xebec, his corsairs ran out their cannon and raised their muskets, ready to do battle if the merchant refused to yield.

Janszoon was Haarlem born and, like many of his fellows, had taken to the sea at an early age. He disdained the merchant life from the beginning, choosing to serve on one privateer or another, and thus mixing patriotism with profit. In 1618, while enjoying some R&R at Lanzarote, in the Canaries, he was snagged by Algerian raiders. Learning of his experience, the captain, Suleyman Reis, gave him the choice of being sold on the slave block or turning pirate and serving as one of his officers. To Janszoon, it wasn't a hard choice at all.

Shortly thereafter, Janszoon converted to Islam. Whether the conversion was genuine or merely to improve his employment prospects, only he knew. Janszoon also married a Mudejar, that is, one whose family was one of those evicted from Moorish Spain. From Cartagena, to be precise. She had good connections, not only in Algeria, but also in Morocco. Janszoon was a conscientious man, in his own way, and despite the new marriage continued to send money to his first wife, back in Haarlem.

The premier Moroccan pirate base was Sallee, on the Atlantic coast, only fifty miles from the Straits of Gibraltar. It wasn't long before Janszoon decided that his job opportunities were better there. They were. Soon after his arrival, the Sallentines declared independence, and established a council of corsair captains to govern themselves. Janszoon had the traits most valued by the corsairs—intelligence, daring, and luck—and found himself elected their first Admiral. The sultan of Morocco laid siege to Sallee, was repulsed, and then "confirmed" Janszoon's appointment. Janszoon shuttled back and forth between Sallee and Algiers, navigating the treacherous politics of both cities. He had returned to Sallee fairly recently, and had decided to lead a corsair sweep—as much to maintain his reputation as for the actual revenue involved.

The warships of the Sallee Rovers were small, because a bar in the harbor forced deep draft vessels to unload if they wanted to enter. However, size wasn't everything. A rover was packed with cannons and experienced fighters, and its hull was carefully maintained to maximize its speed. The Spanish ship had cannon, true, but it was debatable whether its crew even knew how to fire them. And most of its hull space was taken up by cargo.

Would the Spaniard flee, fight, or simply surrender? Further flight to the northwest was clearly hopeless; he would have to swing wide to avoid the Taraf al-Gharb, the Cape of the West. What the English called "Trafalgar."

The bow of the Spanish merchantman started to swing away. Ah, they meant to head north, beach themselves on the coast, and hide in the pine forests beyond. Janszoon gave a hand signal. Shots rang out, and the Spanish helmsman crumpled. A few moments later, the merchantman struck. The battle was over.

The pile of loot on the main deck grew as the corsairs emptied barrels and chests from the hapless merchant ship and stripped valuables off its crew and passengers. This public collection was necessary, for every pirate risked life and liberty, not for a mere wage, but for a share of the spoils. The corsairs had to be sure that they were each getting a fair share. Ten percent of the loot went to the government, to support the maintenance of the defenses; forty-five percent to the outfitter, as reimbursement; and the remainder to the officers and crew. Each officer received three shares, each cannoneer two, and common seamen one apiece.

Of course, the real loot were the crew and passengers of the Spanish ship. They would be sold on the slave market, and the proceeds divided according to the pirate rule. The rich or well-connected captives would be ransomed, and the poor ones would spend the rest of their miserable lives in servitude.

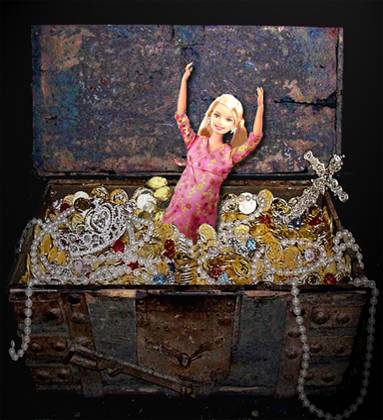

Janszoon's eyes were drawn to one of the treasures, a figurine which had been carefully packed in a padlocked chest. Clearly, it was considered to be of great value. It puzzled Janszoon greatly. It reminded him a little of some of the statuettes of the African tribes, because of the exaggerated feminine endowments. But it was clearly a depiction of a Caucasian, and the workmanship was much finer than that of any African artifact he had ever come across. Was it Dutch? Venetian? Or something even more exotic. Perhaps it was from the Mughals, or the Cathayans?

And what material was it made out of? Janszoon and his officers debated the issue. It certainly wasn't a metal. But neither was it glass, or wood, or horn, or ceramic. Janszoon finally decided to simply ask its erstwhile owner to provide a full explanation. The owner had an arm around the shoulders of a lad with similar features. A son or nephew, no doubt, who, but for this disastrous misfortune, would have joined the family business.

He pointed to the man. "Come here. We found you holding this chest, did we not?"

"Yes, sir. I meant no disrespect, sir."

"What is your name, and how and where did you get this little fancy?"

"My name is Sergio Antonelli, and I am a citizen of Venice. I bought the figurine there, but it comes from a town in Germany called Grantville."

Janszoon frowned. "Grantville? I have heard of it. Another fabled land, like the kingdom of Prester John."

"Oh, there is no doubt of its existence. There is a delegation in Venice right now. They have been explaining their alchemical and medical arts to our own professore, and trading for zinc, and glassware, and alcohol. They aren't magicians, but the Council of Ten is convinced that they are, as they claim, visitors from the America of the future. And you surely know how good the council's spies are."

"And this figurine? What is it made of?"

"The material is called plastic, and the Americans made it alchemically. It will be years before they can make more of it, however. They don't have the right equipment anymore."

"How did this artifact come into your hands?"

"I bought it from a fellow Venetian, Federico Vespucci. He actually went to Grantville two or three years ago. He is my second cousin. He sold most of the figurines, but we kept a few as an investment. Most of the buyers were collectors, and they will take their purchases off the market. Which meant that the price of the few resalable ones would go up. Way up."

"So why were you carrying it on a boat to Cadiz?"

Sergio sighed. "I had a new business idea—one that needed a license from the king of Spain. I needed an extraordinary present to ingratiate myself with the royal family, and this plastic statue seemed perfect."

"So, these men of the future. Do their arts include the arts of war?"

"I have heard that they have muskets which can fire very quickly, and that they used them to destroy a Spanish army. I have heard that they have supplied cannon to the king of Sweden, with which he defeated an Austrian force. And I have even heard, although I only half believe it myself, that they have used a flying fort of some kind to turn back the Danish fleet from the coast of Germany."

A sailor cuffed him. "Don't speak nonsense to the admiral or I'll cut out your tongue."

Janszoon held up his hand. "It may not be a nonsense. I heard something about a flying machine from a fellow Dutchman who sailed with the Algerines. I thought he was just having a joke at my expense, but perhaps I misjudged him . . . May Allah have mercy on his soul.

"So I would like to know more about Grantville. Have you been there? Or met any Americans?"

The merchant hesitated.

"If you lie to me, I will know it," Murad Reis declared. "And I will make you wish that you were in the hands of the Spanish Inquisition."

The merchant shuddered. "No, I haven't, but I have met those who have, and have questioned them closely. And I have been in the part of Germany, it is called Thuringia, where Grantville now lies."

"And do you know their language?"

The merchant chose his words most carefully. "I speak the English of our own time. I have heard that visitors from England have been able to speak to them, but that the 'up-timers' have many words which we do not, and that some familiar words have strangely altered meanings.

"Also, it appears that many of them have now learned German, or Latin, and so we can converse with them in those languages as well."

He waited for another question. The wait was a long and nerve-wracking one, because Murad Reis had been given much to think about.

"When I take my ships upon the sea, there is both danger and opportunity. The same is true of dealings with this Grantville, but the risks and rewards are a hundredfold greater. But if don't act, I—and the Republic of Sallee—will ultimately lose to those who make the gamble.

"To act as I must, I must have information, and it must be from someone I can trust. So, I will release you."

The merchant brightened. "Your Excellency, may it please you—"

"I will release you . . . conditionally. You will guide my son Cornelis to Grantville and see to it that he comes to no harm, and meets those in a position to aid us. I will hold your son as hostage in my palace, but he will be treated as a guest and not worked like a slave. When you return my son to me, I will return yours to you, and I will set you both free, with many gifts.

"You will have two years in which to complete the journey. If my son doesn't return, or if he doesn't reach this Grantville, then your son will suffer the consequences."

"What . . . consequences?"

"Use your imagination. Then multiply by ten."

Murad Reis looked fondly at his son. "Dear boy, the future of our family may well depend on how well you conduct yourself in Grantville."

"I will not disappoint you, Father, Allah willing."

"As soon as we land, visit the tomb of Sidi Ahmad Ibn Ashir, and pray for a safe and successful trip." Ashir was one of the patron saints of Sallee.

"How long will I have to prepare for the journey to Grantville?"

"I can give you a month. Learn this merchant's strengths and weaknesses, as you will be dependent on him. Have him teach you English and polish up your German."

Janszoon paced the deck, thinking. "I will have you sail with him to a Dutch port." Sallee, at this moment, had a treaty with the Dutch Republic. That didn't mean that Sallee Rovers wouldn't attack a Dutch ship if it seemed delectable enough. For the sake of propriety, if they did so they would fly the Algierian flag and take the captives to Algiers. As a matter of policy, Sallee and Algiers were never both at peace, simultaneously, with the same European power.

"In Holland, be sure to go to Haarlem and visit my first wife, I will have gifts for you to give her. And our daughter, Lysbeth. Your older sister. Remind her that she has a standing invitation to come visit me here in Sallee.

"Oh, and find out if they have any news of your older brother, Anthony. Is he still in New Amsterdam? Have he and Grietje had any children yet?" Anthony Jansen Van Salee was Moroccan born, and had married Grietje Reyniers in 1629, on board a ship bound to America.

"Then make your way to Grantville. Learn how they build their ships, how they cast their cannon. Aye, how they fly!

"I will give you a letter which you pass on, if the circumstances warrant it, to this Michael Stearns. It will offer him a full alliance if he agrees that he and his people will convert to Islam."

Cornelis Jansen Van Sallee thought it was a pity that the merchant had not been to Grantville personally. He really had one question of his own about Grantville. It wasn't about shipbuilding, or cannon casting. It was . . . did the women of Grantville really look like this—what was the name the merchant gave the figurine? This . . . "Barbie"?

Author's Note:

In our timeline, Jan Janszoon (1575-1641) became Admiral of Sallee in 1619 but moved to Algiers in 1627. I have "butterflied" his life so that he is back in Sallee by 1634.