It drives my wife crazy, and I'm sorry it does, but I can't really help it.

All the little sayings and homilies.

Such as: There's a heartbeat in every potato; you need that like a hen needs a flag; I'd trust him about as far as I could sling a piano; use it up, wear it out, do it in, or do without; you'll never be hung for your beauty; fools' names, and their faces, are often seen in public places.

I could go on and on. I got a million of 'em. I got them all from my mother, who got them all from her mother. Little kernels of wisdom. Cosmic fortune-cookies, if you like.

They drive my wife absolutely BUGFUCK.

"But honey," I'll say in my best placatory voice (I'm a very placatory fellow, when I'm not writing about vampires and psychotic killers), "there's a lot of truth in those sayings. There really is a heartbeat in every potato. The proof of the pudding really is in the eating. And handsome really is as—" But I can see that it would be foolish to continue. My wife, who can be extremely rude when it serves her purpose, is pretending to throw up. My four-year-old son walks in from the shower, naked, dripping water all over the floor and the bed (my side of the bed, of course), and also begins to make throwing-up noises.

She is obviously teaching him to hate me and revile me. It's probably all Oedipal and sexual and neo-Jungian and dirty as hell.

But I have the last laugh.

Two days later, while this self-same kid is debating which card to throw away in a hot game of Crazy Eights, my nine-year-old son tells him, "Let me look at your hand, Owen. I'll tell you which card to throw away."

Owen looks at him coldly. Calculatingly. Pulls his cards slowly against his chest. And with a humorless grin he says: "Joey, I'd trust you just about as far as I'd spring a piano."

My wife begins to scream and roll around on the floor, foaming, pulling her hair out in great clots, drumming her heels, crying out: "I WANT A DIVORCE! THIS MAN HAS CORRUPTED MY CHILDREN AND I WANT A FUCKING DIVORCE!"

My heart glows with the warmth of fulfillment (or maybe it's just acid indigestion). My mother's homilies have slipped into the minds of yet another generation, just as chemical waste has a way of seeping into the water table. I think: Ah-hah-hah-hah! Another triumph for us bog-cutters! Long live the Irish!

Another of this wonderful woman's wonderful sayings (I told you—I got a million of 'em; don't make me prove it) was "Milk always takes the flavor of what's next to it in the icebox." Not a very useful saying, you might think, but I suspect it's not only the reason I'm writing this introduction, but the reason I'm writing it the way I'm writing it.

Does it sound like Harlan wrote it?

It does?

That's because I just finished the admirable book which follows. For the last four days I have been, so to speak, sitting next to Harlan in the icebox. I am not copying his style; nothing as low as that. I have, rather, taken a brief impression of his style, the way that, when we were kids, we used to be able to take a brief impression of Beetle Bailey or Blondie from the Sunday funnies with a piece of Silly Putty (headline in the New York Times Book Review: KING OFFERS EERILY APT METAPHOR FOR HIS OWN MIND!!).

How do I know this is what has happened? I know because I have been writing hard for about twenty-five years now—which means (as Harlan, or Ray Bradbury, or John Crowley, or any other writer worth his or her salt will tell you) that I have also been reading hard. The two go together. I am always chilled and astonished by the would-be writers who ask me for advice and admit, quite blithely, that they "don't have time to read." This is like a guy starting up Mount Everest saying that he "didn't have time to buy any rope or pitons."

And part of the dues you pay while you're doing this hard reading, particularly if you start your period of hard writing as a teen-ager (as most of us did—God knows there are exceptions, but not many), is that you find yourself writing like whoever you're reading that week. If you're reading Red Nails, your current short story sounds like that old Hyborian Cowboy, Robert E. Howard. If you've been reading Farewell, My Lovely, your stuff sounds like Raymond Chandler. You're milk, and you taste like whatever was next to you in the refrigerator that week.

But this is where the metaphor breaks down . . . or where it ought to. If it doesn't, you're in serious trouble. Because a writer isn't a carton of milk—or at least he or she shouldn't be. Because a writer shouldn't continue to take the flavors of the people he or she is currently reading. Because a writer who doesn't start sounding like himself sooner or later really isn't much of a writer at all, he's a ventriloquist's dummy. But take heart—little by little, that voice usually comes out. It's not easy, and it's not quick (that's one of the reasons that so many people who talk about writing books never do), but there comes a day when you look back on the stuff you wrote when you were seventeen . . . or twenty-two . . . or twenty-eight . . . and say to yourself, Good God! If I was this bad, how did I ever get any better?

They don't call that stuff "juvenilia" for nothing, friends'n'neighbors.

The imitativeness shakes out, and we become ourselves again. But. One never seems to develop an immunity to some writers . . . or at least I never have. Their ranks are small, but their influence—at least on this here New England white boy—has been profound. When I go back to them, I can't not imitate them. My letters start sounding like them; my short stories; a chunk of whatever novel I'm working on, maybe; even grocery lists.

Lovecraft. Raymond Chandler (and, at second hand, Ross Macdonald and Robert Parker). Dorothy Sayers, who wrote the clearest, most lucid prose of our century. Peter Straub.

And Ellison.

That's really where it hews to the bone, I guess. When you take it right back down home, you come to this: the man is a ferociously talented writer, ferociously in love with the job of writing stories and essays, ferociously dedicated to the craft of it as well as its art—the latter being the part of the job with which writers who have been to college most frequently excuse laziness, sloppiness, cant, and promiscuous self-indulgence.

There are folks in the biz who don't like Harlan much. I don't think I'm telling you anything you don't know; if you know the imprint this book bears, then you probably know enough about speculative fiction to know that. These anti-Harlan folks offer any number of reasons for their dislike, but I believe that a lot of it has to do with that ferocity. Harlan is the sort of guy who makes an ordinary writer feel like a dilettante, and an ordinary liver (i.e., one who lives, not a bodily organ which will develop cirrhosis if you pour too much booze over it) feel like a spinster librarian who once got kissed on the Fourth of July.

Coupled with the ferocity of purpose is a crazed confidence—the confidence of a man who does not just walk wires but runs across them full-tilt-boogie. There are folks who find this trait equally unendearing. People who are afraid don't like people who are brave. People who eat pallidly and politely at the Great Banquet of Life (Chew that fish—there might be a bone in it! Skip the beef—if you eat enough of it, you get cancer of the bowel! No eggs—cholesterol! Heart attacks! Eat the carrots. Eat the carrots. They're safe. Boring, but safe.) resent people who dash wildly up and down, trying some of this, scarfing up some of that, swallowing something really gruesome and barfing it back up.

Put another way, Harlan knows now—and has, I would guess, since about 1965—that if you're gonna talk that talk, you gotta be able to walk that walk; that if you got the flash you better have the cash, and that sooner or later you gotta put up or shut up. He rides the shockwave.

All of this comes through admirably in the man's fiction and essays (as it damn well should; otherwise his impact would die with him), and I think that's the reason I always end up writing like the guy after I've been reading the guy. It's the force of his personality, the sense of Harlan Ellison as a living person that's caught in the lines. There are people who don't like that; there are many people who are convinced that Harlan is some sort of trick, like that miniature guillotine that will slice a cigarette in two but leave your finger intact.

Others, who know that few tricksters and literary shysters can hang around for better than twenty-five years, publishing fiction which has steadily broadened its area of inquiry and which has never declined in its energy, know that Harlan is no trick. They may begrudge him that apparently inexhaustible energy, or resent his chutzpah, or fear his refusal to suffer fools (of some people it is said they will not suffer fools gladly; Harlan does not suffer them at all), but they know it isn't a trick.

The book which follows is a case in point. I'm not going to pre-chew it; if you want someone to chew your food for you, send this book back to the publisher, get a refund, and go buy a few volumes of Cliff's Notes, the mental babyfood of college students everywhere for the last forty years or so. You won't find one on Harlan, and I hope you never will (and speaking of wills, why not put it in yours, Harlan? "NO FUCKING CLIFF'S NOTES; IF YOU WANT TO KNOW WHAT GOES ON IN DEATHBIRD STORIES, GO READ A COPY, YOU FUCKING MENTAL MIDGET!" God, I sound like Harlan today—don't you think so?). Certainly you won't find a Harlan-Ellison-in-a-nutshell in this introduction.

But I will point out that these stories and essays range from almost Lovecraftian horror ("Final Trophy") to existentialist fantasy ("The Cheese Stands Alone," with its almost talismanic repetition of the phrase "My fine stock") to the riotously funny (take your pick; my own favorite—maybe because it's gifted with a title that even Fredric Brown would have admired—"Djinn, No Chaser") to good old nuts-and-bolts science fiction ("Invulnerable").

The essays have a similar range; Harlan's essay on the Saturn fly-by of the Voyager I bird could fit comfortably into an issue of Atlantic Monthly, while one can almost see "The 3 Most Important Things in Life" as a stand-up comedy routine (it's a job, by the way, that Harlan knows, having done it for a while in his flaming youth).

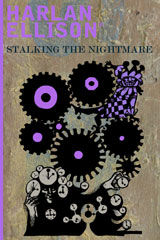

Harlan's wit, insight, and energy inform all of these stories and essays. Are they uneven? Yes, of course they are. While I haven't been given the "lawyer's page"—that is, the dates of copyright on each short story and essay, along with where each was previously published—just the Xerox offprints I've been sent suggest that there is also a wide range of time represented in Stalking the Nightmare. Different typefaces and different return addresses tell part of the tale: the evolution in style tells part of it; the growth of confidence and ambition tells much more of it.

But even the earliest stories bear the unmistakable mark of Ellison. Take, for example, "Invulnerable," one of my favorite stories in the present collection—in fact, I guess I'd go a step further (God hates a coward, right?) and say it's the favorite, mostly because of the original way Harlan handles a very old idea—here is Superman and Krypto the Wonder Dog for thinking adults. Exactly how old is the tale? Without the lawyer's page it's impossible to tell, but it's possible to don the old deerstalker hat and make a couple of Sherlock Holmes-type deductions just the same. First, "Invulnerable" was originally published in Super-Science Fiction, and the illustration (just a hasty pen-and-ink; you're not missing a thing) is by Emsh, whose work I haven't seen in years. So, still wearing the deerstalker hat, I'd guess . . . maybe 1957. How far off am I?

Take a look at the lawyer's page, if you want. If it's more than five years either way, you're welcome to a good horselaugh at my expense.*

* Readers of the above-entered praise, seeking in vain for the story "Invulnerable" (published in the April, 1957 issue of Super-Science Fiction—you get the Mad Hound of the Moors award for deductive logic, Steve), will be confused, bemused and even dismayed—as will Stephen King—to find the work absent from this book. I suppose some sort of explanation is in order. It goes like so: "Invulnerable" was one of the original selections included in the twenty tales slated for this collection. It was among the tearsheeted stories sent to Steve prior to final editing, so he could write his Foreword in a leisurely fashion. Subsequently, when I went back over the stories and read them more closely, I realized some of the older tales desperately needed extensive revision, updating, smoothing and rethinking. One of these stories was "Invulnerable." I had forgotten that Steve mentioned it so prominently in his essay. The qualities admired by Steve are definitely present in the story, but the quality embodied in Steve's remark that "there's a certain amount of dating" was too great to allow to pass untended. Yet to leach out that dated aspect would have meant virtually writing a new story. I decided not to do it. I started revising the original manuscript, written very early in my career, and realized after three pages that the job was akin to rebuilding an edifice that had been burned to the ground, from bottom up. Instead of doing that, I decided to include a recent story, "Grail," at twice or three times the length. So Stephen King has whetted your appetite for a "lost" story, one that I may some day rewrite and update completely. But search not for "Invulnerable" in these pages. It ain't here.

Harlan Ellison

So there's a certain amount of dating in the story; it doesn't just happen to the best of us, it happens to all of us. And yet, even "way back then, in those fabled Old Days when there was such an artist as Emsh and such an organ as Super-Science Fiction, we find Harlan Ellison's true voice—clear in tone, dark in consideration. This was the era when science fiction's really big guns—guys like Robert A. Heinlein, for instance—were touting space exploration as The Great Panacea for All Mankind, The Last Frontier, and The Solution to Just About Everything. There's a certain amount of that in "Invulnerable" (but then, why not? I suspect there's a certain amount of that wistful fairy-tale still in Harlan's soul . . . and mine . . . and maybe in yours, too—read "Saturn, November 11th," and see how you react), but Harlan also sounds the horn of the skeptic, loud and clear.

Forstner was waiting. He was surrounded by the top brass. The place was acrawl with guards; guards on the guards; and guards to guard the guards' guards. The same old story. It wasn't as noble an endeavor as they would have had me believe.

It was an arms race, an attempt for superiority of space before someone else got there . . .

Yeah, it was an arms race. We all know that . . . now. But to have said it back in the days when Good Old General Ike was still the top hand in the old Free World Corral (and let's not forget his chief ramrod, good old Tricky Dick Nixon—I know we'd like to, but maybe we'd better not), when Reddy Kilowatt was supposed to be our friend and nuclear power was going to solve all of our energy problems, back when the only two stated reasons we had for getting Up There were to beat the Russians and to study the sun's corona for the International Geophysical Year (which every subscriber to My Weekly Reader knew as IGY) . . . to have had such a dark thought back in those days—and about us as well as them—well, that was tantamount to treason. It's a little amazing that Harlan got into print . . . unless you know Harlan, of course. And it's damn fine to have it here, preserved between the boards of this admirable book.

But I promised not to chew your food for you, didn't I?

So I'll get out of here now. Harlan's going to come along very soon, grab you by the earlobe, and drag you off to a dozen different worlds. You're going to be glad you went, I promise you (and you may be a little bit surprised to find you've made it back alive).

Just one final comment, and then I promise to go quietly: there's no significant correlation between the quality of a writer's writing and the quality of that same writer's personality. When I tell you that reading Harlan is overwhelming enough to start me writing like the guy—taking his flavor as my mother said milk takes the flavor of whatever you put it next to in the icebox—I am speaking of ability, not personality.

Harlan Ellison's personality is every bit as striking as his prose style, and this makes the man a pleasure to dine with, to visit, or to entertain. But let's tell the gut-level, bottom-line truth. Most of you reading this are never going to eat a meal with Harlan, visit him in his home, or be visited by him. He gives of himself in a way that is profligate, almost dangerous—as does any writer worth his salt. He'll tell you the truth in a manner which is sometimes infuriating (see "The Hour That Stretches" or "!!!The!!Teddy!Crazy!!Show!!!" in this volume, or the classic short story "Croatoan," where Harlan managed to accomplish the mind-numbing feat of simultaneously pissing off the right-to-lifers and the women's liberationists) and always entertaining . . . but don't confuse these things with the man, do not assume that the work is the man. And ask yourself this: why in Christ's name would you want to make any assumption about the man on the basis of his work?

I for one am sick unto death with the cult of personality in America—with the assumption that I should eat Famous Amos cookies because the dude is black and the dude is cool, that I should buy an Andy Warhol print because People magazine says he only owns two shirts and two pairs of shoes, that I should go to this movie because Us says the director has given up cocaine or that one because Rona Barrett says the director has recently taken it up. I am sick of being told to buy books because their writers are great cocksmen or heroic gays or because Norman Mailer got them sprung from jail.

It doesn't last, friends'n'neighbors.

The cult of celebrity is cogitative shit running through the bowel of the intellect.

For whatever it's worth, Harlan Ellison is a great man: a fast friend, a supportive critic, a ferocious enemy of the false and the foolish, maniacally funny, perhaps insecure (I'm not sure what to make of a man who doesn't smoke or drink and who still has such crazed acid indigestion), but above all else, brave and true. If I knew I was going to be in a strange city without all the magical gris-gris of the late 20th century—Amex Card, MasterCard, Visa Card, Blue Cross card, driver's license, Avis Wizard Number, Social Security number—and if I further knew I was going to have a severe myocardial infarction, and if I could pick one person in all the world to be with me at the moment I felt the hacksaw blade run down my left arm and the sledgehammer hit me on the left tit, that person would be Harlan Ellison. Not my wife, not my agent, not my editor, my accountant, my lawyer. It would be Harlan, because if anyone would see to it that I was going to have a fighting chance, it would be Harlan. Harlan would go running through hospital corridors with my body in his arms, commandeering stretchers, I.C. support units, O.R.s, and of course, World Famous Cardiologists. And if some admitting nurse happened to ask him about my Blue Cross/Blue Shield number, Harlan would probably bite his or her head off with a single chomp.

And do you know what?

It doesn't matter a damn.

Because time flies, friends. Tempus just keeps fugit-ing right along. And as 1982 becomes 1992 becomes 2022 becomes 2222, no one is going to care that Ellison once wrote stories in bookshop windows, or drove an old Camaro with cheerful, adroit, scary, leadfooted abandon, or that Stephen King ("Who's that, Tonto?" "Me don't know for sure, Kemo sabe, but him write just like Harlan Ellison.") once nominated him The Man I Would Most Like to Have With Me in a Strange City When My Ventricles Go on Holiday. Because by 2222, the people reading fiction (always assuming there are any people left in 2222, ha-ha) aren't going to have a hope of taking dinner with Harlan, or shooting a rack of eight-ball with him, or listening to him hold forth on the subject of why Ronald Reagan would be a better President if he 1) lit a firecracker, 2) put the firecracker between his teeth, and 3) jammed his head up his ass. By 2222, Harlan will have put on his boogie shoes and shuffled off to whatever Something or Nothing awaits us beyond this Vale of Quarter Pounders.

If the cult of celebrity sucks (and take your Uncle Stevie's word for it; it does indeed suck that fabled Hairy Bird), it sucks because it's as disposable as a Handi-wipe or a Glad Bag or the latest record by the latest Group of the Moment. Andy Warhol ushered in the celebrity era by proclaiming that, in the future, everyone would be famous for fifteen minutes. But fifteen minutes isn't a very long time; while any number of you guys and gals out there may have read the science fiction of H.G. Wells or the mysteries of Wilkie Collins, how many of you have read such big bestsellers of thirty plus years ago as Leave Her to Heaven, Forever Amber, or Peyton Place?

You don't make it over the long haul on the basis of your personality. Fifteen years after the funny guys and the dynamic guys and the spellbinders croak, nobody remembers who the fuck they were.

Luckily, Harlan Ellison has got it both ways—but don't concern yourself with the personality. Instead, dig into the collection which follows. There's something better, more lasting, and much more important than personality going on here: you've got a good, informed writer working well over a span of years, learning, spinning tales, laying in the needle, doing handstands and splits and pratfalls . . . entertaining you goddammit! Everything else put aside, is anything better than that? I don't think so. And so I'll just close by saying it for you:

Thank you, Harlan. Thank you, man.

Stephen King

Bangor, Maine

1982