Back | Next

Contents

SECTION 1

We stare, all twelve of us, at the entrance to the small shop. Concealed as we are, in doorways and behind cars and trucks, we hardly need the deepening dusk to hide us further. Still, I’m glad the dark is coming. We may need it yet before we’ve done what we have to do.

I am sitting behind the wheel of a rust-eaten, dirty 1978 Sunbird, its once-brilliant white now covered with mud and dust. I’ve tuned the radio to the CBC, where some annoying violin concerto seems to be taking the entire night to complete. Drumming my fingers on the pale-blue steering wheel, I look through the window and impatiently wait for something to happen.

I am sitting behind the wheel of a rust-eaten, dirty 1978 Sunbird, its once-brilliant white now covered with mud and dust. I’ve tuned the radio to the CBC, where some annoying violin concerto seems to be taking the entire night to complete. Drumming my fingers on the pale-blue steering wheel, I look through the window and impatiently wait for something to happen.

Outside, the smells from the old Cantonese restaurant on the corner fill the air. Running children screech and yell obscenities to each other as they pass by me. Suddenly, a gust of air brings with it the cloying odor of the nearby rubber factory, and I close the window to keep out the smell.

The air is like soup. Thick, sticky, the stuff I really hate. I think about it for a minute, then laugh at myself. Of all the nights to pick to carry this thing through, I have to choose the one most like a sauna. I’ve never liked hot weather. I like it even less tonight.

I switch the radio to the AM band and push the second button. The Blue Jays are in Boston tonight, and good old Fenway is rocking to the sound of Wade Boggs hammering yet another double off the Green Monster. This one scored two runs, which puts the Sox on top 3-0. And it’s the eighth inning. Stupidly, because the game is far less important than the job I’ve come here to do, I tense up. The Jays can’t afford to lose another one.

As the sky darkens, I continue to listen. The top of the ninth starts off well, with Fernandez walking and Gruber singling up the middle. But then Moseby, who can’t seem to get anything going this season, swings wildly at ball four, and Bell pops up to second base. But up comes Barfield, who once again leads the league in home runs, and I feel my excitement begin to mount. If he can put one out of here, right over that damned wall in left field, we’re right back in it. If not, we may not get another chance. Not off Clemens.

Strike one. It’s okay, Jesse, just keep a good eye. A ball. Fine, keep looking hard. Strike two. God damn! You struck out three times yesterday, Jess, don’t do it again. A foul back. Okay, you’re still alive. Clemens steps off the mound. Once. Twice. Ball two. More delay. Two more fouls, then ball three. Full count, Jess. Take your time.

The crowd must be on its feet, ready for the final strike. The strikeout king of the American League, up against the home-run king of the majors. I look at my hands gripping the wheel, and the knuckles are white with the tension. Sweat pours off my forehead and into my eyes. I’m ready, Jesse. Hammer that sonofabitch out of there. Clemens winds. Waits. Kicks. And…

“Derek!” The cry tears through the dusk. I whip around in my seat and see something round, black and round, coming at me through the air. Instinctively, I open the car door, and in a tiny second I am lying on the sidewalk. My car shatters in the blast, and as the flames fly from it, I rise to a crouch and run towards the others.

A bomb! A goddamned bomb! I can’t believe it. Nobody throws bombs in Toronto. This is a safe city, for chrissakes!

But it’s happened, and I have to do something about it. Something a little more decisive than complaining how tawdry the city has become. I dart behind a garbage can that smells like dead cats, then I drop to my hands and knees and crawl over to where Brando stands, barely concealed by a drainpipe at the side of an old button factory.

“What’s up?” I ask.

“I don’t know,” he replies, precisely as I expected. “Seems someone threw a bomb.”

“Thanks,” I reply. “Awfully good of you to tell me that. Care to help me remove the shrapnel?”

“Get stuffed, Derek,” he says. “You asked me something and I gave you an answer. What else do you want?”

He’s right, of course. My sarcasm is unwarranted. Still, sometimes Brando’s stupidity is alarming. And I wonder: is it innate, or does he force the dumb act a little too hard?

Still, I apologize. “Okay, I’m sorry. But did you see what happened? Did you see who threw the bomb? It was at me, that’s all I know, and I was watching the doorway the whole time.”

“I know,” Brando replies. “So were we. And the bomb didn’t come from there. But it didn’t come from the other side either. The passenger side of the car got hit, and that was the side closest to the door. Unless someone’s invented a boomerang bomb.”

I chuckle. Hell, that was almost funny. Very nearly witty. Given enough time, I may discover that Brando is human.

A tap on my shoulder. I whirl around. McManus looks down on me from his six-foot-six frame, then opens his denim jacket and pulls out a knife. I motion for him to put it away, but he simply shakes his head and spits on the sidewalk.

“Stan,” I say, “we don’t need a knife. We’ve never needed your knife. Knives don’t do much against bombs.” McManus smiles his crooked smile and feels the edge of the knife. It draws a drop of blood, and he is satisfied.

“Stay here,” I whisper to both of them. “I’m going to find Tom and Jacques. Watch that door.” I don’t wait for their answers, and I’m sure they won’t give them, anyway. Both of them like to play strong and silent, and of all the members of our little group, Brando and McManus are the ones I like and trust the least. I can’t believe they aren’t simply stupid.

Running between buildings and behind cars and boxes, I finally come to where Jacques crouches under a low fire stair in a narrow alley. A doughnut store is on his left, a kids’ used clothing store on his right. He does not see me, but stares instead at a small black squirrel that nibbles on the remains of a green apple. When I touch his shoulder, he leaps away from the wall and back into the alley, rising with his hand on the trigger of his gun. The squirrel, quite sensibly, disappears up the oak tree nearby.

“It’s only me, Durrell,” I say. “Please don’t shoot me. I have enough problems this particular minute.”

Smiling, Jacques hides his gun under his brown jacket. I see the sweat pouring from his arms as he closes the jacket again, then I wonder how he can stand being so hot. Still, I’ve never seen him without a jacket of some kind, so I don’t bother asking him about it. Jacques is his own man, and that jacket is part of him.

“You’ve survived the explosion, I see,” he says, his English flawless and elegant, even though French is his first language. I wish I knew French well enough to know if he is as perfect in that language as he is in mine. Polymaths unnerve me, especially if they know my language better than I do. Jacques certainly does.

“Yes,” I say. “It was close, but I managed to get out of the car in time. I didn’t notice anyone rushing to find out, though.”

Jacques smiles again. “True,” he says. “Of course, had we done so, you would likely have reprimanded us, even if you were dead. You tend to be a little unwavering, good leader. You know that, don’t you?”

I nod. “Yes. I know that. And you’re right, I would have been upset. But we’re here for a reason, and we have to fulfill that. Wouldn’t it have been a good idea to keep me alive?”

Jacques scratches the back of his neck with his right hand, then places his left there as well, to massage his neck. “To tell you the truth, Derek,” he says, “I would guess that no one considered you in any real difficulty. You have an uncanny ability to survive. I’ve never even seen you injured. There seemed no reason to be overly concerned with you this time.”

“I’ve never had a bomb tossed at me, Monsieur Durrell. Even for a battle-hardened guy like me there are occasional first times.” He shrugs and resumes his stare at the shop. “But that doesn’t matter anymore, and to be honest I don’t really care. I’m okay, and I’ve lived through worse. Did you see where the bomb came from?”

Durrell thinks for a moment, then turns to me and says, “I may be mistaken, but I think it dropped from above you. Perhaps from the tree. It most certainly did not come from the shop, or from anywhere else on that side of the street.” He ponders for a second, then repeats, “Yes, the tree seems most likely. I suppose someone is still up there.”

The tree! Of course. I knew the bloody thing was there, even though I took no notice of it. Awfully stupid of me, considering it offers the perfect hiding place for anyone suspecting an attack that evening. What bothers me most, though, is that we were expected at all. This operation was only planned two nights ago, and not until last night were such details as the timing in place at all. If we were expected, then one of us gave it away.

Who?

More importantly, why?

“Check it out, Jacques,” I order, and Durrell nods, crouches, and disappears.

I take off my running shoe and smack it twice against the stair above my head, the signal for Tom to come to this spot. In less than a minute, Tom appears, his speed belying his short, fat frame, and he stands before me neither breathing hard nor sweating. His smile is infectious, and although I had planned to be stern, I find myself smiling back and shaking my head.

“Yes, sir!” Tom mockingly snaps to attention. “Of what service might I be to you, sir?” He salutes, and insists on holding the salute until I reply. He is funny, but at times his humor is annoying.

“Did you see where the bomb came from?” I ask. “Jacques says it might have been tossed from the oak tree near my car. Brando and McManus have no idea, not that I expected them to. Have you spoken with any of the others since the explosion? Any information at all?”

“No,” Tom replies, in his forthright manner. “To all questions. Matter of fact, I didn’t even see the bomb until it exploded. I was watching someone moving in the upstairs window of the shop. The explosion came from behind me. The only thing I want to know is this: Why aren’t the cops here?”

I snap my head back. That’s an awfully good question. This is Toronto, after all. Police don’t ignore things like explosions. They don’t happen here. Never. So where are they?

“If they’re not here by now,” I suggest, “they can’t be far away. Dammit, Tom, why do you always have to think of the bad things? We don’t want them here. Not now. If they come, we can’t pull this thing off.” I pause, then look back at the little fat man in front of me. “What do we do now?”

Tom merely smiles. “Well, Derek,” he begins, “if you want my suggestion,” and he waits for me to nod, “I think we’d better strike now. Or forget about it for a week or so, until the police stop searching this area for further trouble.” He stops and listens, then continues. “And if we’re going to do it now, then would you please excuse me so that I can place myself back where I came from? I’d hate terribly to find the man we’re looking for simply walked out the back door and went for a pizza somewhere. We sort of need him, if you know what I mean.”

“I know what you mean,” I reply as a smile spreads over my face. “All right, go back where you came from and wait for the signal. We’re a bit ahead of schedule, but we don’t have any more time. It’s now or never.”

“Nice line, chief,” Tom says. “Sounds like a good song title.”

I pick up a half-rotten apple and throw it at him. He scampers away just in time, and it lands in the street. From out of nowhere, a small black dog appears, grabbing the apple in its teeth and scurrying out of sight. The street resumes its silence.

Tom Samuelson is the leader of this group of would-be vigilantes. I’m in charge now, of course, but only because I’m paying them and because I have some experience in military leadership. Not that I’ve ever really fought, having served in a Canadian army that has done no fighting since Korea, but I was an officer for five years following my years at the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ontario; two of those years a 2nd lieutenant, two more as a full lieutenant, and the final year as captain. Tom’s training was simpler: he led a street gang in Detroit for three years. Once in Toronto, he hit the streets with a couple kids in Cabbagetown, then migrated to Chinatown for the bigger stuff. But compared to Detroit, Toronto has no street scene at all, and I’ve often wondered why Tom came here in the first place. The pickings are pretty good, I guess, but the action is very, very subdued. Still, when I decided to round up a gang of toughs, Tom’s name was at the top of everybody’s list. He’s well-known here, and better than that, he’s well-respected.

Tom, Jacques Durrell, Stan McManus, Marlon Thompson (nicknamed Brando), Reginald Goate (Billy, of course), Branko Verdi, Dennis Nichol (a poet, for God’s sake), Allen Jonathan, Darcy McCrimmon (former hockey player), Roger P. Lowenstein (who claims to have been a lawyer), and Bartholomew Simpson (who insists on being called Simmie)—these are the people I’ve been working with, the men I am leading into battle, if battle it can be called. With these men, some of whom I am trusting only on Tom’s testimony, I will be attempting what until now I’ve found impossible.

With these men I will try to conquer Amber.

Amber. That incredible, beautiful, terrifying world where Random rules as king and where Corwin the Murderer wanders free. Amber, land of the treacherous unicorn, world of misbegotten beauty and unrealized power. Land of order, land of oppression, land of destroyed dreams.

Amber, the land where once my father lived and breathed. Until he was murdered. The fratricide of Eric, Prince of Amber. Eric, my father.

I’ve read the books, all five of them. Nine Princes in Amber, The Guns of Avalon, Sign of the Unicorn, The Hand of Oberon, The Courts of Chaos. I’ve even read the other two, but they had nothing to do with my father, so I threw them away. What bothers me most is that the only point of view we have is Corwin’s, and there is no doubt in my mind that Corwin is a liar.

For one thing, he begins the books without a memory. I realize that the Amber series is devoted to showing how he regains and makes use of that memory, how he reassimilates his native world, but there is no way of knowing that the memory he regains has anything to do with fact. We think it is true because he tells us, and if nothing else, Corwin is believable. His sense of ethos is astoundingly good. But there’s more to truth than ethos, and there’s more to history than memory. Corwin’s chronicle is, in one sense at least, a history of one period of Amber’s existence, and like all historians, we are forced to accept whoever’s version is extant. For the history of Achilles’ wrath we turn to Homer, for the history of my father’s death we turn to Corwin.

Oh, I know. Corwin didn’t really write The Chronicles of Amber, Roger Zelazny did. But I’m not sure that’s true. Or, if it’s true, I’m damned sure it doesn’t matter. Zelazny didn’t create Amber, he just took what was there already and wrote about it. In effect, he reworked Corwin’s own manuscript. The book is Corwin’s, and therefore the text we have is Corwin’s. If there is a problem, it is in establishing truth. Corwin, as I’ve already said, is a liar.

Maybe “liar” is too harsh. Maybe he just doesn’t remember properly. The most interesting thing about the story as Corwin presents it is that he is the one who gets to the top. How the hell can you believe a storyteller who knows all along that he is destined for the top? Sure, he turns down the chance to be king, but it’s pretty obvious he could have had the throne if he’d wanted it. Certainly, Oberon thought he should, or at least so the books say. But my father’s role seems passed over, my father’s earnest attempts to save Amber from destruction. He died for Amber, and nobody seems to care.

That’s why I’m here. I want to get to Amber. As far as I know, there’s only one way to do that, unless you’re from Amber in the first place. Somebody has to send me there.

That somebody, I have found out, lives above a small bookstore in downtown Toronto. What he’s doing here, I’m sure I don’t know. All I know is that he’s my only ticket to Amber.

Inside the shop, the window reveals, two young women are looking over the racks of used hardcovers. From their appearances they seem to be university students, but that is purely a guess. The clerk, an overweight, bearded man in his late twenties, dressed in cheap polyester dress pants and a long-sleeved white shirt, watches them for a moment, then gets their attention and points to the door. For a few minutes the women ignore him and continue their browsings. My impatience grows.

Finally, after three more polite reminders by the bearded clerk, the two women pay for a few books and leave the store. They are laughing as they walk away, seemingly amused at their mischievous defiance in keeping the store open late. As they pass by me, about ten yards away, I see the bags slung over their shoulders, bulging with books. The bags bear the insignia of York University, my own alma mater.

Resisting with considerable difficulty the desire to join them and talk about York, a difficulty made even more severe by the fact that these women are not hard to look at, I turn my attention back to the shop. The clerk walks from shelf to shelf, straightening and jotting down some scribblings on a piece of paper. He returns to the cash register, opens it, removes the tape, and puts the money and the tape in a large envelope. Tucking the envelope under his arm, he disappears for a few minutes through a doorway in the back, then he returns to the cash register and locks it. Finally, he turns out all the lights but one, locks the front door from the inside, and disappears once more through the back. A minute passes, then another. At last I see the signal, a double flash of the headlights of a car, that lets me know he has left the shop for good.

At long last I am ready to begin. Fear mixes with excitement as I start my walk towards the back of the shop. Our plan is hardly elaborate, but it doesn’t have to be. Beside the back door of the shop is a door to the stairway that leads up to the apartment. My job is to knock on the door and wait for an answer. If I get one, and the person answering is the one we want, then I’ll play it by ear. If there is no answer, I am to signal the others. Two of them will come forward and break down the door, and then three more will join them—and me—as we rush through and up the stairs. That will make six of us: hardly necessary to deal with one person, but I’m counting on force to get my demands through. By myself, I might not be able to demand anything.

Of course, this all assumes resistance. It may be that our contact will do everything I want, either because he’s afraid of me or because he would be willing to do it anyway. Perhaps all he wants is money. There’s even a chance that he can’t help me at all. I don’t believe that could happen—I researched the whole thing far too long—but I suppose it’s possible. If so, however, it’s a possibility I don’t want to think about.

The night is dark now, and the sounds of the Toronto traffic buzz through the city. About to make my move, I am suddenly wary, suddenly filled with doubt. What if this is all for nothing? What if the contact can’t help me? What if everything goes as planned, and I actually get to Amber? Can I really do what I want to do? Can I—with only twelve men to help me—do what I have to do to make any difference in Amber itself? Can a commando squad (for that is what we are) infiltrate to the heart of a kingdom?

Nothing is worked out, not properly. In my haste to get moving, I’ve overlooked almost everything that’s important. Part of that is because I simply don’t know what to expect. The other part is that I’m afraid to think of what might be. Worst of all, though, I haven’t even told my squad—my gang, my warriors—that they might be leaving this world with me. How could I? Who would believe me?

I’m not even sure I believe myself. Suddenly, this whole thing seems so crazy.

The door is painted light blue, and the number 37 is painted on it in pink. Pausing for a moment to reflect on my prepared entrance speech, I stare at the brown mat at my feet. Turn back, idiot! I seem to hear my voice say, turn back and go home. But I’ve prepared well enough not to listen to my own cowardice, and so with shaking hands I reach towards the doorbell button. Pushing it, I hear a low buzzer sound in the depths of the building.

I wait.

And I wait.

And I wait a little more. Nothing. Not a sound, not a peep, not even a bang or a whimper. Nothing so strong as the pitter-patter of little feet reaches my eager ears. For a moment, I consider leaving. That thought is destroyed, however, not by a noise from inside the building, but instead from one behind the building. Turning around, I see Jacques Durrell walking towards me.

“No answer, right?” he asks softly. “All of this for nothing. I can hardly believe it.”

“Now come on, Jacques,” I mutter, turning back to the door. “Maybe the guy’s in the shower. Maybe he’s gone out for some milk. Or beer. Hell, maybe he’s in the can. Maybe he just doesn’t answer the door after ten o’clock.” All of these possibilities are real, of course, but even so, I am scarcely convinced. The truth is likely simpler: our man has gone to a pub, or perhaps to a movie. Suddenly I feel sick.

Jacques studies me closely. Speaking slowly, as if to force me to understand each word, he suggests, “I suppose we had best proceed with the other plan. As it is, we are wasting time.” After a few seconds, he adds, “Do we have your permission, Derek?”

The other plan, as we developed it a few days ago, is to break down the door and find what we want without any help. Six of us would go upstairs, while the other six wait outside for any sign of trouble or our client’s return. A perfectly reasonable alternative, I realize at once, but here, at the very door I’ve sought for several months, the idea seems suddenly inappropriate, suddenly less than possible. Even if I get over my dislike of breaking and entering (which I am embarrassed to admit), the fact remains that I may simply not find what I want. I think that, when all is said and done, I need our contact to provide what I’ve come for. I find it hard to believe that I can get to Amber by myself.

The other plan, as we developed it a few days ago, is to break down the door and find what we want without any help. Six of us would go upstairs, while the other six wait outside for any sign of trouble or our client’s return. A perfectly reasonable alternative, I realize at once, but here, at the very door I’ve sought for several months, the idea seems suddenly inappropriate, suddenly less than possible. Even if I get over my dislike of breaking and entering (which I am embarrassed to admit), the fact remains that I may simply not find what I want. I think that, when all is said and done, I need our contact to provide what I’ve come for. I find it hard to believe that I can get to Amber by myself.

The pause has been too long. Jacques, rarely impatient, becomes so now. Shaking his head and sighing, he asks me, “Do we proceed, Derek, or do we go home? Please make up your mind. If we are not to go through with this, I have things I would like to do.” He crosses his arms.

“One more minute, Jacques,” I reply with a brief smile. “Just give me a few seconds. I’ve never done this before.”

“We have,” he insists. “We know how to do it.” Then, much more softly, “Yes, Derek. A few more minutes. But that is all. If you have not given the signal by then, I will tell the others to leave. Please do not keep me waiting.” Unnerved by his brusqueness, I return my gaze to the blue door with the pink numbers. Suddenly, without warning, the sheer silliness of my conversation with Jacques strikes me funny, and the sound of my full laughter breaks the drone of traffic in the night.

It breaks as well, almost on cue, the silence that surrounds the door. With a shatter of wood, the door swings open, and through it race three large men. All three have knives drawn, and all three seem to know where they are going. One dives towards Jacques, a second dashes by him into the street. The third, I hate to say, is barreling straight towards me. Purely out of fear, with reflexes born of a lifetime of running away, I tear at the knife in my pocket, hoping to get it out and in front of me. My heart pumps madly.

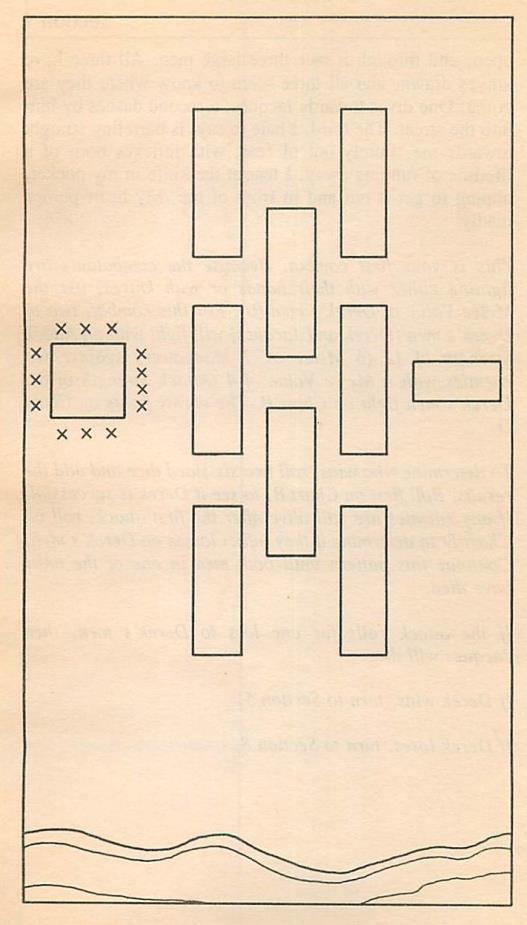

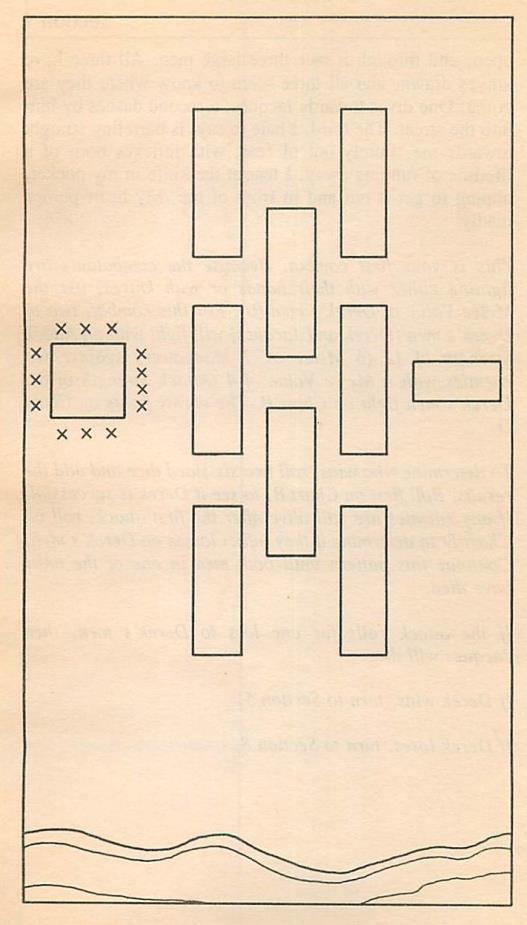

This is your first combat. Because the combatants are fighting either with their hands or with knives, use the Melee Value of Derek’s men (6). For this combat, two of Derek’s men (Derek and Jacques) will fight with an Attack Strength of 12 (6 Melee X 2 Manpower) against two enemies with a Melee Value of 4 (Attack Strength of 8). Derek’s men fight on Chart B. The enemy fights on Chart D.

To determine who wins, roll two six-sided dice and add the results. Roll first on Chart B, to see if Derek is successful. If any enemies are still alive after the first attack, roll on Chart D to determine if they inflict losses on Derek’s men. Continue this pattern until both men in one of the units have died.

If the attack calls for one loss to Derek’s men, then Jacques will die.

If Derek wins, turn to Section 5.

If Derek loses, turn to Section 8.

Back | Next

Framed

I am sitting behind the wheel of a rust-eaten, dirty 1978 Sunbird, its once-brilliant white now covered with mud and dust. I’ve tuned the radio to the CBC, where some annoying violin concerto seems to be taking the entire night to complete. Drumming my fingers on the pale-blue steering wheel, I look through the window and impatiently wait for something to happen.

I am sitting behind the wheel of a rust-eaten, dirty 1978 Sunbird, its once-brilliant white now covered with mud and dust. I’ve tuned the radio to the CBC, where some annoying violin concerto seems to be taking the entire night to complete. Drumming my fingers on the pale-blue steering wheel, I look through the window and impatiently wait for something to happen. The other plan, as we developed it a few days ago, is to break down the door and find what we want without any help. Six of us would go upstairs, while the other six wait outside for any sign of trouble or our client’s return. A perfectly reasonable alternative, I realize at once, but here, at the very door I’ve sought for several months, the idea seems suddenly inappropriate, suddenly less than possible. Even if I get over my dislike of breaking and entering (which I am embarrassed to admit), the fact remains that I may simply not find what I want. I think that, when all is said and done, I need our contact to provide what I’ve come for. I find it hard to believe that I can get to Amber by myself.

The other plan, as we developed it a few days ago, is to break down the door and find what we want without any help. Six of us would go upstairs, while the other six wait outside for any sign of trouble or our client’s return. A perfectly reasonable alternative, I realize at once, but here, at the very door I’ve sought for several months, the idea seems suddenly inappropriate, suddenly less than possible. Even if I get over my dislike of breaking and entering (which I am embarrassed to admit), the fact remains that I may simply not find what I want. I think that, when all is said and done, I need our contact to provide what I’ve come for. I find it hard to believe that I can get to Amber by myself.