CHAPTER IV

HOW GANELON, COUNT OF MAYENCE, WAS NEARLY SMOKED IN THE COMPANY OF TWO HOGS, AND WHAT FOLLOWED THEREAFTER.

GANELON’S castle was situated on the loftiest peak of the Hartz Mountains, the Blocksberg. There, in the midst of the Hercynian forest, which cannot be less than twenty-four leagues in length by ten in breadth, towered the eyrie of this vulture. One road, and only one, traversed this vast extent of forest, but Ganelon took care that it should always be in good repair; it was a courtesy which he felt was due from him to the travellers he despoiled.

The count had gathered round him a collection of the best assorted ruffians of every country; Saxons, Danes, Lombards, Jews, and Saracens, lent him a hand to forward the interests of the Evil One. One morning he called them all together, and said to them—“I have pleasant news for you. We have the opportunity of playing a pretty trick on some Saxon traders. I have just been informed that a caravan, consisting of thirty mules, laden with treasure, and conveyed by a small escort, is about to cross the Hartz Mountains this morning, to attend the fair of St. Denis. I have conceived the design of protecting French commerce, and putting a stop to the opposition which is meditated against it. Under the protection of our patron saints, the two thieves, we will make ourselves masters of this venture.”

Ganelon and his rascals placed themselves in ambush along the border of the forest, and before long saw a thick cloud of dust rising along the road in the distance.

“Here,” cried they, “beyond a doubt, are those we are waiting for. Let us save them three-quarters of their journey;” and they rushed forward, sword in hand. The two opposing storms of dust approached each other, and from the further came the cry, “Hi! what are you doing? You’ll destroy the beasts!”

Ganelon and his men had charged into the midst of an army of porkers, driven by Westphahan swineherds.

The surprise of the assailants was so great that it allowed the swineherds time to form in a body and draw their knives; and those weapons were not to be sneered at, readers mine, for they were those which butchers use for quartering and cutting up carcases.

Ganelon remained for a moment undecided. That hesitation was fatal. The Jews and Saracens, to whom pork is a forbidden dish, did not think it worth while to press matters further. They accordingly retreated, taking with them several of their fellows, who thought their chief would retire into ambuscade again. But a Count of Mayence is not the man to despise bacon and sour-crout. So Ganelon, gazing over the ocean of lard which grunted at his feet, began to lick his lips, and think that here was a booty which was quite as well worth having as the other. But the swineherds knew with whom they had to deal, and, indeed, had come in such numbers solely because they expected an attack. They rushed on the count and his lances, and began to hamstring the horses. The horsemen -were soon rolling in the dust among the hogs. Two of them, who showed an inclination to resist, were very properly run through on the spot, and mingled their lifeblood with that of two pigs that had been run down by the horses. The others were disarmed, and allowed to escape. As for Ganelon, they tied his hands tightly behind his back.

“Now then,” said the head swineherd, “before they pluck up courage to come back in force, suppose we hang their leader?”

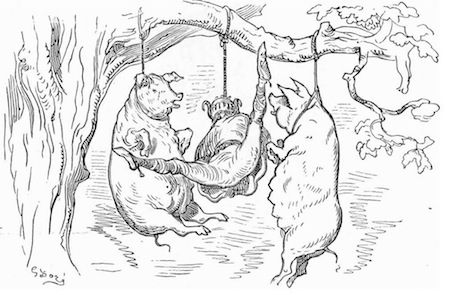

This idea appeared very agreeable to everybody except Ganelon, who uttered the most furious oaths. But they dragged him, armed as he was, under an oak, and then, having chosen a stout bough worthy of such fine fruit, they adjusted the cord round his neck. Then they brought the two slaughtered pigs—the only victims of the Count of Mayence—and having fitted each with a strong hempen cravat, suspended them one at each end of the bough, reserving the post of honour for the knight. These preparations concluded, Ganelon was dragged, bound hand and foot, to the place of execution. He writhed about in the madness of his rage, foaming at the mouth, calling on his companions in villany, and cursing them for their desertion. In vain did he struggle—a score of sturdy arms speedily hoisted him up between his two companions.

“Pull down his visor,” said the head swineherd to the man who was on the bough adjusting the noose, “the monster is hideous enough at the best of times—what will he look like presently?”

Ganelon continued to struggle at the end of the cord, to the great delight of the spectators, who, though they found him tenacious of life, did not complain on that account.

Meanwhile, the count began to find that death was rather slow in coming. He had hanged too many not to know something about it, and in this instance it was so personally interesting to him that it could not fail to arrest his attention. “These knaves,” said he to himself, “have made a sad bungle of the job. I ought to have been dead some time.” And then it dawned on him that he was only suspended, not hanged. His executioners had put the noose round the gorget of his helmet.

“Oho!” said Ganelon to himself, “this is quite another affair, and all is not yet lost, possibly. Only, if I continue my gambols, I may, perhaps, give the hint to these idiots, and they might hang me again more carefully. I’ll sham dead, and it’s odd if the Evil One doesn’t send some one to my aid. It would be very inconsiderate of him to let me die like this!”

Nevertheless, for one who wasn’t dead, the count was uncommonly near death. The blood rushed to his head, and filled his eyes. He began to hear a dismal noise in his ears, like the tolling of a bell. His mouth grew dry, his lips were contracted, and presently his limbs gave one last convulsive struggle. Ganelon confessed to himself that all was over, and lost consciousness while faintly murmuring a final imprecation. The swineherds, encouraged by their success, and not wishing to leave the two hogs for the enemy, resolved to cook and eat them. They posted sentinels, collected their herds, and prepared to celebrate their victory with a feast.

“It strikes me,” said the chief swineherd, “if we were to omit an opportunity of throwing a light on a point of interest to culinary science, we should regret it all our lives. A rare and remarkable opportunity offers itself to us now—we must not allow it to escape us. Are you not all equally anxious, with myself, to learn whether it takes longer to smoke a peer than a pig?”

The suggestion was a great success. They collected a heap of sticks and leaves under each of the three victims, and lighted it. And then, joining hands, they began to dance round, uttering wild shouts.

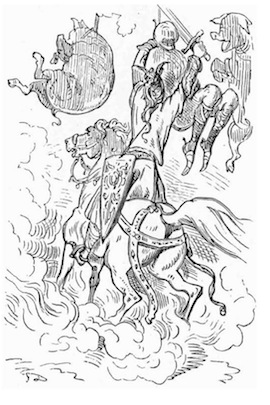

Roland, it so chanced, was returning this way from Saxony, whither he had been sent by Charlemagne. He had, certes, in war laid many a man dead in his path, but he had never permitted a cruelty to be committed in his presence. His indignation was roused by these vile chantings, this demoniac dance, and all the hideous apparatus of torture. He was not long in deciding what course to pursue. He rode at the dancers, and dispersed them with the flat of his sword, not deigning to honour them by using against them the edge, which he reserved for foemen more worthy of him.

Then he made to the hanging man, and in order to cut the rope, had to keep Veillantif for a few seconds trampling on the embers in the midst of the flames. The Count of Mayence tumbled heavily into the middle of the fire. Roland dismounted, with one hearty kick sent him rolling some fifty paces, and then ran to assist him.

His first care was to relieve him of his helmet. When he recognised whose life he had saved, I must admit he made a grimace. The Count of Mans, the faultless mirror of chivalry, could feel no liking for such wretches, but he was not the less ready to aid them.

Ganelon re-opened his eyes. His succession of tumbles had done more to recover him than all the eau-de-cologne in the world would liave done. When he saw his preserver, he heartily wished it had not been Roland.

“Are you hurt, count? What can I do to assist you?”

“I don’t want your pity, Knight of Blaives. Why have you rescued me? I am not of a race or of a disposition likely to love those who place me under an obligation, and it would have been less bitter for me to die than to owe my life to you!”

“I forgive these words, Sir Ganelon. You have just undergone such a shock, that you have evidently not quite recovered your senses!”

At these words the Count of Mayence was seized with such a paroxysm of rage, that he found strength enough to try to avenge the insult. He flung himself on his preserver, and seized him by the throat.

“You’ll make yourself ill again,” said Roland, coolly freeing himself from the other’s grasp. “You forget that you are not quite well yet. Allow me to administer a curative process which you ought to undergo.”

With these words he caught his adversary by the scruff of the neck, dragged him beside his horse into the heart of the forest, tied his hands with the cord that had already served him as a halter, and bound him fast to a tree.

Ganelon foamed at the mouth, and bit his lips till the blood came. The fury in his eyes would have been terrible to any but Roland.

“Now, count, calm yourself. You see I am anxious to cure you in spite of yourself. Nothing conduces to meditation like solitude. Now that you are alone, you will have time for reflection; and if you are a wise man, you will say to yourself, ‘This Roland is a very good fellow not to break every bone in my body;’ and, since you are a coward and a villain, you will possibly say, ‘This Roland was a fool not to kill me outright.’ You will finish by perceiving that such a man as I can only despise one like you. Meditate, and if Heaven is kind, it will counsel you prudence. Anyhow, do not make an uproar, for fear your enemies should disturb your reflections, which, in that case, very likely, might come to a termination at the end of a rope. I will call at your castle, and send some one to your assistance: as my royal uncle is awaiting me at Cologne, you must excuse my attending on you further. Don’t forget, moreover, that I am, and always shall be, ready to honour you with a thrust of my lance or blow of my sword, in spite of the disgust I should feel at having to cross swords with a highway robber!”

Ganelon’s thoughts were so frightful that the human language is unable to express them. He hung down his head, and when he found himself alone he wept. His tears fell upon the grass; an innocent caterpillar, wandering in search of food, mistook them for dewdrops, tasted them, and died of the poison.

Two hours after, the swineherds had disappeared, and Ganelon re-entered his castle. Eight hours after, all whom Ganelon believed to be acquainted with his mishap were dead.

Six months after, he was at the court of Charlemagne, seated at the same table as Roland. Pork was placed on the table, but the Count of Mayence refused it.

“You bear malice, count,” said Roland; “that is wrong. Who knows?. perhaps you are refusing an old brother in misfortune.”

Ganelon turned livid, but he did not stir. After the feast was over Roland came to him.

“Have you forgotten,” he asked, “the threats you uttered and the offer I made to you in your domain on the Hartz?”

“I never forget,” said the Count of Mayence.

Here, then, was the prime cause of Ganelon’s hatred of Roland.