CHAPTER III

CHARLEMAGNE’S CORTEGE.

CHARLEMAGNE determined to celebrate the fortunate issue of his campaign. Jousts and tourneys were organised, and heralds were sent out far and wide; and before long knights began to pour in from the various provinces: some to show their courage and exercise their strength and skill, others in the hope of enriching themselves with the spoils of their vanquished adversaries.

The spot chosen for the tournament was an extent of velvet sward situated at the edge of a forest of oaks that were five hundred years old. A semi-circle of low hills formed a sort of amphitheatre, in the centre of which a vast area, reserved for the combatants, was surrounded with palisades. There were two entrances to the lists—one on the north, the other on the south—each wide enough to admit of the passage of six knights on horseback abreast. Two heralds and six pursuivants had charge of each of these entries. Small detachments were scattered about here and there to maintain order—no easy task, for the inhabitants of the surrounding country, with their wives, had assembled from all quarters alongside of the camp. On them it was difficult to impress a due observance of discipline, and the unmanageable came in for showers of blows that were not laid on less heavily because it was a conquered country.

On a level space not far from the northern gate were raised twelve gorgeous pavilions, reserved for the twelve principal French champions who held the lists. Pennons with their colours, and those of their lady-loves, fluttering in the wind, waved in the sunlight like flying serpents. Each knight had his shield suspended before his tent, under the charge of a squire.

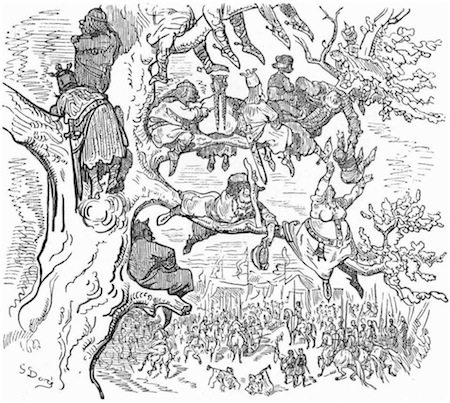

Further off, less costly tents served as lodgings for numerous warriors, who were drawn together either by friendship or want of means. This community formed a quaint sort of town, which had, as it were, suburbs consisting of stable-sheds, and huts of all sorts, occupied by armourers, farriers, surgeons, and artisans, whose presence on such occasions was indispensable. Merchants at these times were exempted from all tolls and taxes, and accordingly the Jews had come to sell Venetian trinkets and Oriental perfumes to the ladies; the Bretons brought their honey for sale, and the Provencals displayed their clear olive oil; and amid all these good things were to be seen, rambling about at random, jugglers, troubadours, minstrels, and all other classes of poor Bohemians, whose wits are sharp if their purses are scant. On the borders of the wood was erected a pavilion more magnificent than all the others—it was that of Charlemagne; it was of cloth of gold, with purple stripes, powdered with gold eagles, and it was so bright that one would have needed the eye of an eagle to support its lustre for an instant. All about it were knights, squires, lackeys, and pages, coming and going as thickly as bees in a hive around their queen. On either side of the royal tent, and all along the edge of the forest, were erected seats for the spectators of rank, who promised to be numerous. They flocked-in every hour in crowds, so delighted were they with spectacles of this description, and, above all, so desirous were they of beholding Charlemagne, whose name had already begun to resound through Europe. The royal box, more lofty than the others, and more richly decorated, was a little in front of the tent. Charlemagne had ordained that the Queen of Beauty should share this with him, in order that she might be surrounded by the most valiant knights and the most lovely ladies. The two retinues attended on her amid incessant peals of mirth and merriment.

Finally, my dear readers, to finish the picture, figure to yourselves, situated half-way between the lists and the forest, and surmounted by a huge iron cross, a Gothic chapel, in which, each morning, Turpin, the good and gallant Bishop of Rheims, officiated as priest in the presence of the kneeling multitude.

At length the day of the tournament arrived. There had been many jousts before, but never had there been one of equal magnificence. From the earliest dawn the places were all occupied. Even the old trees were as thickly loaded with curious spectators as a plum-tree in August; and the good folks were right to crowd so, for had they lived their lives six times over, they would never have seen anything equal to the sight again. ft was absolutely necessary for the soldiers to lay about with their pike-staves, in order to calm the eager ardour of the most enthusiastic; but nobody took any notice of thumps that, under any other circumstances, would have been received with an ill grace.

All of a sudden a flourish of trumpets made the air resound. A glittering advanced-guard entered the enclosure and took up their position, and then Charlemagne entered the arena at the head of a numerous escort of knights and nobles, and of ecclesiastics in rich vestments. Enthusiasm knew no bounds.

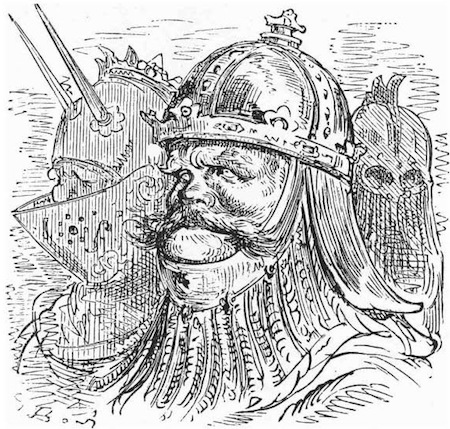

“Montjoie! Montjoie!” resounded on every side. Charlemagne, who later in life affected the greatest simplicity in dress, had assumed for this great occasion the most brilliant attire. His shirt was of fine linen, its border enriched with gold embroidery. His tunic was of silk, plated with gold, and was covered with precious stones of surpassing brightness—emeralds, rubies, and topaz. His armlets and girdle were chased with the most exquisite art, and his alms-pouch, which hung at his side, was besprinkled with pearls and gems enough to dazzle a blind man. His brow was bound with a glittering diadem.

His whole figure shone with an unaccustomed splendour, and he greatly surpassed in magnificence the grandest of his dukes, counts, or barons. His steed, covered with gold and rich trappings, seemed proud of tlie burthen it carried.

The Queen Himiltrude, a Frank by birth, advanced in the midst of her attendants. Her neck was tinged with a delicate rose, like that of a Roman matron in former ages. Her locks were bound about her temples with gold and purple bands; her robe was looped up with ruby clasps. Her coronet and her purple robes gave her an air of surpassing majesty. She was a worthy queen of Charlemagne. But if the queen surpassed all other women in nobleness of mien, Aude, the niece of Gerard of Vienne, and sister of Oliver the Brave, surpassed her as much by her beauty, her grace, and her attractiveness. She wore a light crown, embossed with jewels of all colours. Her hair was fair, falling naturally into becoming curls; her eyes were blue as the sea of the south; her complexion was pink, like the heart of a white rose; and her hands were marvellously small. As she passed Roland, she turned slightly pale. If she had been less lovely, I should have said more about her rich attire; but what is the use, since nobody notices it? The queen must have been very strong-minded, to retain so charming a lady of honour about her person. On seeing the beautiful Aude, every one said, “There, or I’ll die for it, is the Queen of Beauty!”

Aude had near her her sister Mita, fair as herself, but slightly browned by the Spanish sun under which she had been brought up. Two black eyes, full lips, a finely-cut and regular nose, hair hanging down in heavy masses, entwined with long strings of threaded pearls and diamonds—there you have her portrait in a few words.

Her bodice was covered with small pearls; you might have called it a pearl corslet. Indeed, those who saw her pass, admiring her martial bearing and her rich breastplate, gave her the nickname of “the little-knight in pearl.”

After Aude and her sister came a bevy of beautiful young girls, but the people hardly cared to look at them.

At last came the peers and barons, clad in their most splendid armour. What a clash of gold, iron, and steel! How many swords that had won renown! Every one of these puissant arms was worth ten ordinary knights in the tourney-ground—in battle worth a thousand!

It is difficult to explain the agility displayed by these men under such a formidable weight of armour. An ox in these days could scarcely carry one of them. The helmet alone weighed a hundred and twenty-five pounds. They handled like playthings swords which we can hardly lift. “At the battle of Hastings,” says Robert Wace, “Taillefer threw his up, and caught it as if it had been a light stick.” The horses were as powerful as the men. Reared in the rich pastures of the Rhine borders or Bavaria, high-standing and big-chested, they often took part in the contest, tearing with their splendid teeth the enemies of their masters. As soon as they were broken they were clad in iron, to protect them against javelins, spears, and swords.

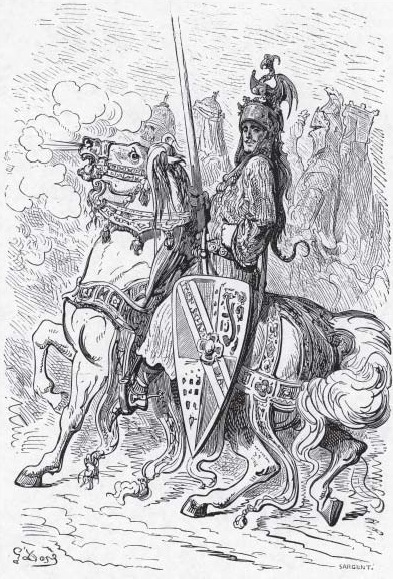

Last of all appeared Roland, Count of Mans and Knight of Blaives, son of Duke Milo of Aiglant, and of Bertha, the sister of Charlemagne. You would have taken him for a statue of iron and marble. His right hand brandished a spear that in these days would serve for the mast of a frigate; his left reposed on his faithful sword Durandal. I know of no one to whom to compare him but the Archangel Michael. His air is at once terrible and tender: should one love him or fear him? He is of such a majestic, awe-inspiring presence, that one can hardly be astonished at any wonders he performs. He appears to belong to a race that is more than human, and you would hardly be surprised were he to drag a star from its sphere or seize a comet by the beard. He is of the same height as Charlemagne, but more imposing in figure and gait. His open countenance invites confidence and inspires respect. When Roland gives a man his hand, the lucky fellow, who is thus honoured as with a royal favour, feels, in the pride of having achieved such a distinction, a greater confidence in his own worth. Roland is mounted on Veillantif, the only horse in the world worthy of such a rider.

Close at hand is Oliver, Count of Genes, the brother of the beautiful Aude. He is hardly second to Roland in strength, in agility, and in appearance. At his side gleams Haute-Claire, and he is mounted on Ferrant d’Espagne, a steed that darts straight towards the foe like an arrow. Then follow Duke Oger, Richard of Normandy, Thibault of Rheims, Guy of Burgundy, Ogier the Dane, Duke Naimes of Bavaria, Girard of Montdidier, Bernard, the uncle of Charlemagne; Miton of Rennes, the friend of Roland; William of Orange, with the short nose, whose name made evil-doers tremble (as you have trembled, little people, at the name of Bogey!); besides a thousand others, not forgetting Turpin, the good Archbishop of Rheims, so learned in the council-hall, so pious in the cathedral, so brave on the field of battle. Turpin was armed in warlike fashion; his rosary and his mace hung side by side; in the handle of the latter was enclosed a precious relic, a bone of St. Clet. He could not wield a sword, for his religion forbade him to shed blood; but it is a fact that his mace weighed a hundred and fifty pounds.

Near Charlemagne was to be seen Wolf, Duke of Gascony—Wolf, who sold his guest and his family—Wolf, who was without a rival in treachery, except Ganelon. Oh, how you will hate the pair of them, my friends, if you -read my story to the end! Wolf was chiefly noticeable for his armour, which was of browned steel, damasked with silver, and which he had purchased of the Saracens in Spain. He is more terrible in peace than in war, and his favourite weapon is the gallows. He was less feared by his enemies than by his subjects, and would sooner knock a man down with a blow of his fist than say, “Thank you.” He was noted for his ingenuity in matters of torture, and has the credit of being the originator of the plan of tying wetted ropes round the temples of his prisoners to make their eyeballs start out of their sockets.. It was he, too, who had them sewed up in freshly-stript bulls’ hides, and exposed to the sun until the hides in shrinking broke their bones. But what is the most awful to tell is that no one had ever seen him in a rage. He was cruel in cold blood from inclination and appetite. The smell of blood delighted him more than frankincense or verbena. Charlemagne hardly spoke to him, and it was with difficulty that he could prevent his dislike of him from appearing.

Count Ganelon, of Mayence, was not quite so bass a savage. At all events, his bravery was unquestionable; he could be a useful councillor, and if the envy with wliich Roland inspired him had not driven him to evil deeds, he might have been one of the foremost of Charlemagne’s followers. A lover of solitude, a taciturn and even savage man, an irreligious unbeliever in all noble sentiments—such was Ganelon in moral disposition. Need I say he had no friends? In height he was hardly six feet and a half, and he wished all those who were taller than he was, even by the breadth of a line, were of his height. His eyes glared from beneath the shadow of his fiery locks, like those of a savage hound. He loved gold only to hoard it, and affected great poverty. You would have thought him one of Attila’s Huns rather than one of the paladins of Charlemagne’s court. Ganelon could not forgive Roland for having rendered him a service on several occasions. The superiority of Charlemagne’s nephew drove him mad. This may, perhaps, surprise some of the younger of my readers, but it is too true that to evil minds gratitude is displeasing and troublesome. But I had better make you acquainted with the particular grievances of the Count of Mayence.