Very well, if neither the undisputed variations that are observed today, nor laboratory attempts to extend and accelerate them provide support for the kind of plasticity that evolution requires, what evidence can we find that it nevertheless happened in the past? There is only one place to look for solid testimony to what actually happened, as opposed to all the theorizing and excursions of imagination: the fossil record. Even if the origin of life was a one-time, nonrepeatable occurrence, the manner in which it took place should still yield characteristic patterns that can be predicted and tested.

Transforming a fish into a giraffe or a dinosaur into an eagle involves a lot more than simply switching a piece at a time as can be done with Lego block constructions. Whole systems of parts have to all work together. The acquisition of wolf-size teeth doesn't do much for the improvement of a predator if it still has rat-size jaws to fit them in. But bigger jaws are no good without stronger muscles to close them and a bigger head to anchor the muscles. Stronger muscles need a larger blood supply, which needs a heavier-duty circulatory system, which in turn requires upgrades in the respiratory department, and so it goes. For all these to all come about together in just the right amounts—like randomly changing the parts of a refrigerator and ending up with a washing machine—would be tantamount to miraculous, which was precisely what the whole theory was intended to get away from.

Darwin's answer was to adopt for biology the principle of "gradualism" that his slightly older contemporary, the Scottish lawyer-turned-geologist, Sir Charles Lyell, was arguing as the guiding paradigm of geology. Prior to the mid nineteenth century, natural philosophers—as investigators of such things were called before the word "scientist" came into use—had never doubted, from the evidence they found in abundance everywhere of massive and violent animal extinctions, oceanic flooding over vast areas, and staggering tectonic upheavals and volcanic events, that the Earth had periodically undergone immense cataclysms of destruction, after which it was repopulated with radically new kinds of organisms. This school was known as "catastrophism," its leading advocate being the French biologist Georges Cuvier, "the father of paleontology." Such notions carried too much suggestion of Divine Creation and intervention with the affairs of the world, however, so Lyell dismissed the catastrophist evidence as local anomalies and proposed that the slow, purely natural processes that are seen taking place today, working for long enough at the same rates, could account for the broad picture of the Earth as we find it.

This was exactly what Darwin's theory needed. Following the same principles, the changes in living organisms would take place imperceptibly slowly over huge spans of time, enabling all the parts to adapt and accommodate to each other smoothly and gradually. "As natural selection acts solely by accumulating slight, successive, favourable variations, it can produce no great or sudden modifications; it can act only by short and slow steps." 8 Hence, enormous numbers of steps are needed to get from things like invertebrates protected by external shells to vertebrates with all their hard parts inside, or from a bear- or cowlike quadruped to a whale. It follows that the intermediates marking the progress over the millions of years leading up to the present should vastly outnumber the final forms seen today, and have left evidence of their passing accordingly. This too was acknowledged freely throughout Origin and in fact provided one of the theory's strongest predictions. For example:

"[A]ll living species have been connected with the parent-species of each genus, by differences not greater than we see between the natural and domestic varieties of the same species at the present day; and these parent species, now generally extinct, have in turn been similarly connected with more ancient forms; and so on backwards, always converging to the common ancestor of every great class. So that the number of intermediate and transitional links, between all living and extinct species, must have been inconceivably great. But assuredly, if this theory be true, such have lived upon the earth." 9

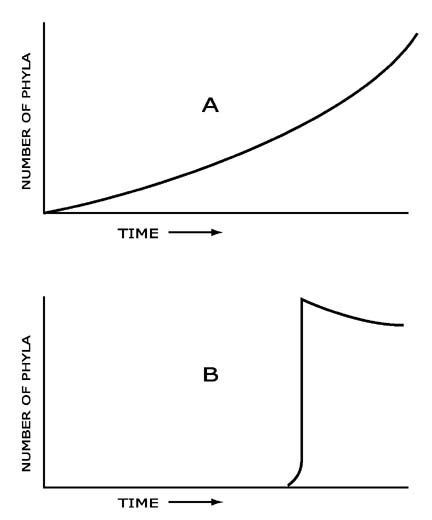

The theory predicted not merely that transitional forms would be found, but implied that the complete record would consist mainly of transitionals; what we think of as fixed species would turn out to be just arbitrary—way stations in a process of continual change. Hence, what we should find is a treelike branching structure following the lines of descent from a comparatively few ancient ancestors of the major groups, radiating outward from a well-represented trunk and limb formation laid down through the bulk of geological time as new orders and classes appear, to a profusion of twigs showing the diversity reached in the most recent times. In fact, this describes exactly the depictions of the "Tree of Life" elaborately developed and embellished in Victorian treatises on the wondrous new theory and familiar to museum visitors and anyone conversant with textbooks in use up to quite recent times.

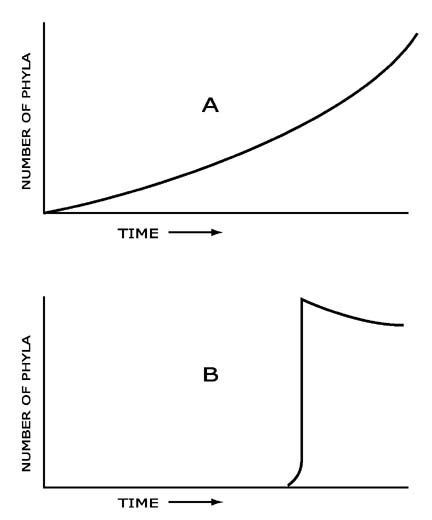

But such depictions figure less prominently in the books that are produced today—or more commonly are omitted altogether. The reason is that the story actually told by the fossils in the rocks is the complete opposite. The Victorians' inspiration must have stemmed mainly from enthusiasm and conviction once they knew what the answer had to be. Species, and all the successively higher groups composed of species—genus, family, order, class, phylum—appear abruptly, fully differentiated and specialized, in sudden epochs of innovation just as the catastrophists had always said, without any intermediates leading up to them or linking them together. The most remarkable thing about them is their stability thereafter—they remain looking pretty much the same all the way down to the present day, or else they become extinct. Furthermore, the patterns seen after the appearance of a new population are not of divergence from a few ancestral types, but once again the opposite of what such a theory predicted. Diversity was most pronounced early on, becoming less, not greater with time as selection operated in the way previously maintained, weeding out the less suited. So compared to what we would expect to find, the tree is nonexistent where it should be in the greatest evidence, and what does exist is upside down.

Darwin and his supporters were well aware of this problem from the ample records compiled by their predecessors. In fact, the most formidable opponents of the theory were not clergymen but fossil experts. Even Lyell had difficulty in accepting his own ideas of gradualism applied to biology, familiar as he was with the hitherto undisputed catastrophist interpretation. But ideological fervor carried the day, and the generally agreed answer was that the fossil record as revealed at the time was incomplete. Now that the fossil collectors knew what to look for, nobody had any doubt that the required confirming evidence would quickly follow in plenitude. In other words, the view being promoted even then was a defense against the evidence that existed, driven by prior conviction that the real facts had to be other than what they seemed.

Well, the jury is now in, and the short answer is that the picture after a century and a half of assiduous searching is, if anything, worse now than it was then. Various ad hoc reasons and speculations have been put forward as to why, of course. These include the theory that most of the history of life consists of long periods of stasis during which change was too slow to be discernible, separated by bursts of change that happened too quickly to have left anything in the way of traces ("punctuated equilibrium"); that the soft parts that weren't preserved did the evolving while the hard parts stayed the same ("mosaic evolution"); that fossilization is too rare an occurrence to leave a reliable record; and a host of others. But the fact remains that if evolution means the gradual transformation of one kind of organism into another, the outstanding feature of the fossil record is its absence of evidence for evolution. Elaborate gymnastics to explain away failed predictions are almost always a sign of a theory in trouble. Luther Sunderland describes this as a carefully guarded "trade secret" of evolutionary theorists and refers to it as "Darwin's Enigma" in his book of the same name, which reports interviews conducted during the course of a year with officials of five natural history museums containing some of the largest fossil collections in the world.10

The plea of incompleteness of the fossil record is no longer tenable. Exhaustive exploration of the strata of all continents and across the ocean bottoms has uncovered formations containing hundreds of billions of fossils. The world's museums are filled with over 100 million fossils of 250,000 species. Their adequacy as a record may be judged from estimates of the percentage of known, living forms that are also found as fossils. They suggest that the story that gets preserved is much more complete than many people think. Of the 43 living orders of terrestrial vertebrates, 42, or over 97 percent are found as fossils. Of the 329 families of terrestrial vertebrates the figure is 79 percent, and when birds (which tend to fossilize poorly) are excluded, 87 percent.11 What the record shows is clustered variations around the same basic designs over and over again, already complex and specialized, with no lines of improvement before or links in between. Forms once thought to have been descended from others turn out have been already in existence at the time of the ancestors that supposedly gave rise to them. On average, a species persists fundamentally unchanged for over a million years before disappearing—which again happens largely in periodic mass extinctions rather than by the gradual replacement of the ancestral stock in the way that gradualism requires. This makes nonsense of the proposition we're given that the bat and the whale evolved from a common mammalian ancestor in a little over 10 million years, which would allow at the most ten to fifteen "chronospecies" (a segment of the fossil record judged to have changed so little as to have remained a single species) aligned end to end to effect the transitions.12

It goes without saying that the failure to find connecting lines and transitional forms hasn't been from want of trying. The effort has been sustained and intensive. Anything even remotely suggesting a candidate receives wide acclaim and publicity. One of the most well-known examples is Archaeopteryx, a mainly birdlike creature with fully developed feathers and a wishbone, but also a number of skeletal features such as toothed jaws, claws on its wings, and a bony, lizardlike tail that at first suggest kinship with a small dinosaur called Compsognathus and prompted T. H. Huxley to propose originally that birds were descended from dinosaurs. Presented to the world in 1861, two years after the publication of Origin, in Upper Jurassic limestones in Bavaria conventionally dated at 150 million years, its discovery couldn't have been better timed to encourage the acceptance of Darwinism and discredit skeptics. Harvard's Ernst Mayr, who has been referred to as the "Dean of Evolution," declared it to be "the almost perfect link between reptiles and birds," while a paleontologist is quoted as calling it a "holy relic . . . The First Bird."13

Yet the consensus among paleontologists seems to be that there are too many basic structural differences for modern birds to be descended from Archaeopteryx. At best it could be an early member of a totally extinct group of birds. On the other hand, there is far from a consensus as to what might have been its ancestors. The two evolutionary theories as to how flight might have originated are "trees down," according to which it all began with exaggerated leaps leading to parachuting and gliding by four-legged climbers; and "ground up," where wings developed from the insect-catching forelimbs of two-legged runners and jumpers. Four-legged reptiles appear in the fossil record well before Archaeopteryx and thus qualify as possible ancestors by the generally accepted chronology, while the two-legged types with the features that would more be expected of a line leading to birds don't show up until much later.

This might make the trees-down theory seem more plausible at first sight, but it doesn't impress followers of the relatively new school of biological classification known as "cladistics," where physical similarities and the inferred branchings from common ancestors are all that matters in deciding what gets grouped with what. (Note that this makes the fact of evolution an axiom.) Where the inferred ancestral relationships conflict with fossil sequences, the sequences are deemed to be misleading and are reinterpreted accordingly. Hence, by this scheme, the animals with the right features to be best candidates as ancestors to Archaeopteryx are birdlike dinosaurs that lived in the Cretaceous, tens of millions of years after Archaeopteryx became extinct. To the obvious objection that something can't be older than its ancestor, the cladists respond that the ancestral forms must have existed sooner than the traces that have been found so far, thus reintroducing the incompleteness-of-the-fossil-record argument but on a scale never suggested even in Darwin's day. The opponents counter that in no way could the record be that incomplete, and so the dispute continues. In reality, therefore, the subject abounds with a lot more contention than pronouncements of almost-perfection and holy relics would lead the outside world to believe.

The peculiar mix of features found in Archaeopteryx is not particularly conclusive of anything in itself. In the embryonic stage some living birds have more tail vertebrae than Archaeopteryx, which later fuse. One authority states that the only basic difference from the tail arrangement of modern swans is that the caudal vertebrae are greatly elongated, but that doesn't make a reptile.14 There are birds today such as the Venezuelan hoatzin, the South African touraco, and the ostrich that have claws. Archaeopteryx had teeth, whereas modern birds don't, but many ancient birds did. Today, some fish have teeth while others don't, some amphibians have teeth and others don't, and some mammals have teeth but others don't. It's not a convincing mark of reptilian ancestry. I doubt if many humans would accept that the possession of teeth is a throwback to a primitive, reptilian trait.

So how solid, really, is the case for Archaeopteryx being unimpeachable proof of reptile-to-bird transition, as opposed to a peculiar mixture of features from different classes that happened upon a fortunate combination that endured in the way of the duck-billed platypus, but which isn't a transition toward anything in the Darwinian sense (unless remains unearthed a million years from now are interpreted as showing that mammals evolved from ducks)? Perhaps the fairest word comes from Berkeley law professor Phillip Johnson, no champion of Darwinism, who agrees that regardless of the details, the Archaeopteryx specimens could still provide important clues as to how birds evolved. "[W]e therefore have a possible bird ancestor rather than a certain one," he grants, " . . . on the whole, a point for the Darwinists." 15 But he then goes on to comment, "Persons who come to the fossil evidence as convinced Darwinists will see a stunning confirmation, but skeptics will see only a lonely exception to a consistent pattern of fossil disconfirmation." It was Darwin himself who prophesied that incontestable examples would be "inconceivably great."

The other example that everyone will be familiar with from museum displays and textbooks is the famous "horse series," showing with what appears to be incontrovertible clarity the 65-million-year progression from a fox-sized ungulate of the lower Eocene to the modern-day horse. The increase in size is accompanied by the steady reduction of the foreleg toes from four to one, and the development of relatively plain leaf-browsing teeth into high-crowned grazing ones. Again, this turns out to be a topic on which the story that scientists affirm when closing ranks before the media and the public can be very different from that admitted off the record or behind closed doors.16

The first form of the series originated from the bone collections of Yale professor of paleontology O. C. Marsh and his rival Edward Cope, and was arranged by the director of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), Henry Fairfield Osborn, in 1874. It contained just four members, beginning with the four-toed Eohippus, or "dawn horse," and passing through a couple of three-toed specimens to the single-toed Equus of modern times, but that was sufficient for Marsh to declare that "the line of descent appears to have been direct and the remains now known supply every important form." More specimens were worked into the system and the lineage filled in to culminate in a display put on by the AMNH in 1905 that was widely photographed and reproduced to find its way as a standard inclusion in textbooks for generations afterward. By that time it was already becoming apparent to professionals that the real picture was more complicated and far from conclusive. But it was one of those things that once rooted, takes on a life of its own.

In the first place, given the wide diversity of life and the ubiquity of the phenomenon known as convergence—which evolutionists interpret as the arrival of closely similar forms from widely separated ancestral lines, for example sharks and porpoises, or marsupial and placental dogs—inferring closeness of relationships purely from skeletal remains is by no means a foolproof business. The coelancanth, an early lobe-finned fish, was once confidently thought to have been a direct ancestor of the types postulated to have invaded the land and given rise to the amphibians. And then the surprise discovery of living specimens in the 1930s and thereafter showed from examination of previously unavailable soft parts that the assumptions based on the fossil evidence alone had been incorrect, and the conclusion was no longer tenable. Hence, if the fossil record is to provide evidence for evolutionary continuity as opposed to the great divisions of nature seen by Cuvier, it is not sufficient that two groups merely resemble each other in their skeletal forms. Proof that it had actually happened would require at least to show one unambiguous continuum of transitional species possessing an incontestable progression of graduations from one type to another. Such a stipulation does, of course, invite the retort that every filling of a gap creates two more gaps, and no continuity could ever be demonstrated that would be capable of pleasing a sufficiently pedantic critic. But a Zeno-like reductio ad absurdum isn't necessary for an acceptance of the reality of continuity beyond reasonable doubt to the satisfaction of common sense and experience. As an analogy, suppose that the real numbers were scattered over the surface of the planet, and a survey of them was conducted to test the theory that they formed a continuum of infinitesimally small graduations. If the search turned up repeated instances of the same integers in great amounts but never a fraction, our knowledge of probabilities would soon cast growing suspicion that the theory was false and no intermediates between the integers existed. A more recent study of the claim of evolutionary transition of types, as opposed to the uncontroversial fact of variation within types stated: "The known fossil record fails to document a single example of phyletic (gradual) evolution accomplishing a major morphologic transition and hence offers no evidence that the gradualistic school can be valid." 17

Later finds and comparisons quickly replaced the original impressive linear progression into a tangled bushlike structure of branches from assumed common ancestors, most of which led to extinction. The validity of assigning the root genus, Eohippus, to the horse series at all had been challenged from the beginning. It looks nothing like a horse but was the name given to the North American animal forming the first of Osborn's original sequence. Subsequently, it was judged to be identical to a European genus already discovered by the British anatomist and paleontologist, Robert Owen, and named Hyracotherium on account of its similarities in morphology and habitat to the Hyrax running around alive and well in the African bush today, still equipped with four fore-toes and three hind ones, and more closely related to tapirs and rhinoceroses than anything horselike. Since Hyracotherium predated the North American discovery, then by the normally observed custom Eohippus is not the valid name. But the suggestiveness has kept it entrenched in conventional horse-series lore. Noteworthy, however, is that Hyracotherium is no longer included in the display at Chicago's Museum of Natural History.

In the profusion of side branches, the signs of relentless progress so aptly discerned by Victorians disappear in contradictions. In some lines, size increases only to reduce again. Even with living horses, the range in size from the tiny American miniature ponies to the huge English shires and Belgian warhorse breeds is as great as that collected from the fossil record. Hyracotherium has 18 pairs of ribs, the next creature shown after it has 19, then there is a jump to 15, and finally a reversion back to 18 with Equus. Nowhere in the world are fossils of the full series as constructed found in successive strata. The series charted in school books comes mainly from the New World but includes Old World specimens where the eye of those doing the arranging considered it justified. In places where successive examples do occur together, such as the John Day formation in Oregon, both the three-toed and one-toed varieties that remain if the doubtful Hyracotherium is ignored are found at the same geological levels. And even more remarkable on the question of toes, of which so much is made when presenting the conventional story, is that the corresponding succession of ungulates in South America again shows distinctive groupings of full three-toed, three-toed with reduced lateral toes, and single-toed varieties, but the trend is in the reverse direction, i.e., from older single-toed to later three-toed. Presumably this was brought about by the same forces of natural selection that produced precisely the opposite in North America.

The perfection and complexity seen in the adaptations of living things are so striking that even among the evolutionists in Darwin's day there was a strong, if not predominant belief that the process had to be directed either by supernatural guidance or the imperative of some yet-to-be identified force within the organisms themselves. (After all, if the result of evolution was to cultivate superiority and excellence, who could doubt that the ultimate goal at the end of it all was to produce eminent Victorians?)

The view that some inner force was driving the evolutionary processes toward preordained goals was known as "orthogenesis" and became popular among paleontologists because of trends in the fossil record that it seemed to explain—the horse series being one of the most notable. This didn't sit well with the commitment to materialism a priori that dominated evolutionary philosophy, however, since to many it smacked of an underlying supernatural guidance one step removed from outright creationism. To provide a purely materialist source of innovation, Darwin maintained that some random agent of variation had to exist, even though at the time he had no idea what it was. A source of variety of that kind would be expected to show a radiating pattern of trial-and-error variants with most attempts failing and dying out, rather than the linear progression of an inner directive that knew where it was going. Hence, in an ironic kind of way, it has been the efforts of the Darwinians, particularly since the 1950s, that have contributed most to replacing the old linear picture of the horse series with the tree structure in their campaign to refute notions of orthogenesis.

But even if such a tree were to be reconstructed with surety, it wouldn't prove anything one way or the other; the introduction of an element of randomness is by no means inconsistent with a process's being generally directed. The real point is that the pattern was constructed to promote acceptance of a preexisting ideology, rather than from empirical evidence. Darwin's stated desire was to place science on a foundation of materialistic philosophy; in other words, the first commitment was to the battle of ideas. Richard Dawkins, in the opening of his book The Blind Watchmaker, defines biology as "the study of complicated things that give the appearance of having been designed for a purpose."18 The possibility that the suggestion of design might be anything more, and that appearances might actually mean what they say is excluded as the starting premise: "I want to persuade the reader, not just that the Darwinian worldview happens to be true, but that it is the only known theory that could, in principle, solve the mystery of our existence." The claim of a truth that must be so "in principle" denotes argument based on a philosophical assumption. This is not science, which builds its arguments from facts. The necessary conclusions are imposed on the evidence, not inferred from it.

Left to themselves, the facts tell yet again the ubiquitous story of an initial variety of forms leading to variations about a diminishing number of lines that either disappear or persist to the present time looking much the same as they always did. And at the end of it all, even the changes that are claimed to be demonstrated through the succession are really quite trivial adjustments when seen against the background of equine architecture as a whole. Yet we are told that they took sixty-five million years to accomplish. If this is so, then what room is there for the vastly more complex transitions between forms utterly unlike one another, of which the evidence shows not a hint?