The 40 Year Quest for a Game that Breaks All the Rules

by Bob Kruger

Dungeons & Dragons turns forty this week. A thorough discussion of D&D involves just about every issue that crops up in game design, so it’s great for a broad overview of the field. But D&D itself is less a game than a set of traditions, an evolving hobby rather than a finished consumer product. At its best, D&D facilitates the creation of a meaningful story that is a surprise to everyone, including the Dungeon Master, and its group dynamics, its mythic subject matter, the element of luck, and even the players’ naïve faith in the rules are instrumental to this effect. In the past week, I’ve talked to several prominent game designers, many of whom were involved with crucial stages of the game's development, to discuss its appeal and test my ideas about how it works.

The One Rule of D&D? Nobody Knows the One Rule of D&D.

In 1997 my friend Jonathan Tweet was working on a new Basic Set to go along with the D&D 3.0 edition, of which Jonathan was chief designer. Jonathan and I got to talking about the project over beers in a Seattle-area pub. We mulled over the influence of miniatures rules—that is, the use of representational figures in three dimensions, usually of metal—on the early editions of the game.

I told Jonathan that I had originally begun learning D&D from the blue-box set I got in 1980 for my eleventh birthday. The blue box was several editions removed from the original 1974 woodgrain-patterned set but still contained unexplained scraps of miniatures rules and lacked clear instructions about the play setup.

The rules I learned from were poorly written and edited, but in a way that somehow rendered the game more appealing. This wasn’t a slick product for a mere consumer; it invited you—practically begged you with its amateurish presentation—to take its ideas and build on them. First, though, you had to decipher those ideas, and boy did I get that wrong. Or did I?

The included dungeon map looked like a game board to me. The miniatures rules about character and monster movement (one inch = 10 feet), coupled with the map legend (one square = ten feet) and the advice that the game was divided in turns, suggested to me that you were supposed to redraw the map to a larger size (with one-inch squares), place miniatures representing the characters at the dungeon entrance, advance so many squares per turn, and then what? There was a Wandering Monster table and a rule that said that you checked once a turn to see if a monster appeared. Maybe at that point you introduced a monster to the board, but where did you put it? At the edge of sight, maybe? A torch illuminated to six inches, or sixty feet; elves had see-in-the-dark, or “infra-,” vision to sixty feet. So unless you were coming up on a corner, you put the monster or monsters at sixty feet. Right?

My interpretations were consistent with the rules and allowed me to play a game with friends that had the trappings of what had been described in magazine articles. Of course, anyone familiar at all with D&D knows it’s not quite this mechanical. Players don’t get to see the map; the Dungeon Master describes each area as the characters enter it, and miniatures are used to help stage encounters but aren’t really needed at all. Most players ignore the movement rules, and a “turn,” which can be divided into ten melee “rounds,” is not a discrete move in the game but a time measurement, and really only a useful concept during combat or when the party is under some kind of deadline pressure.

As I learned these more-accepted ways to play, the game became increasingly fun, and I had this naïve sense that my discoveries would go on indefinitely, leading me and my friends to some ultimate escape.

When I’d finished my reminiscence, Jonathan admitted he found it interesting as an example of how beginners gain a foothold on the game.

Jonathan and I discussed the idea of introducing D&D the way I’d misinterpreted it to be, as a kind of board game, perhaps with modular squares, and then having the players drop the board-game props as the Dungeon Master gained confidence with storytelling and the players with roleplaying. Whether our conversation directly influenced him, I don’t know and neither does he, because he doesn’t remember, but these concepts did get incorporated into Wizards of the Coast’s first Basic Dungeons & Dragons set.

At that time, it had been 17 years since my initial experiments with D&D. Now, another 17 years have passed, and two and a half editions of D&D have come and gone.

Jonathan and I recently met up with our friend 4th Edition designer Rob Heinsoo for lunch. I asked if they’d found D&D as unclear as I had, a question I had failed to ask Jonathan 17 years before. I mean, the rules couldn’t have been as bad as I remembered. How could the game have caught on? Rob and Jonathan, at least, must have understood them.

Nope, they admitted, they really didn’t. So what made them keep at it?

"D&D was hard to play, and it involved a lot of patience, arithmetic, and even tedium,” said Jonathan. “Mapping the dungeon by hand on graph paper is slow. The cool stuff is all in your head, invisible. A D&D session can be a like a six-hour bout of sensory deprivation. If you weren't committed to the quest of killing monsters and taking their treasure, it was the last thing you'd want to do.

“That said, if you wanted to fight monsters, D&D was the only game in town. In 1977, when I started playing, Space Invaders hadn't even appeared yet. We put up with every inconvenience to play that game.

“We tested my introductory D&D sets [at Wizards of the Coast] with kids, so I've watched lots of kids learn D&D cold. When it works, you sometimes see the a-ha moment where a 14-year old realizes that the action is really in your imagination, and that means you can do anything with the game.

“D&D rules don't define your game. Instead, they define the tools you'll use to build your own game."

If Rob couldn’t understand the rules, then absolutely no one should have been able to. In the early seventies while living with his family on an army base in Germany, he’d been a customer of Guidon Games, a mail-order retailer of historical lead figures and war games. Guidon also published rules, including Chainmail, a medieval miniatures game co-authored by Gary Gygax that was the progenitor of D&D. Rob bought the original D&D box set in 1974,1 the year it came out, and he could not understand its sketchy combat system at all.

“Rules problems probably started with the fact that the game wanted you to use dice with strange numbers of sides,” said Rob. “I had six-sided dice, and knew a wargame that used them. When I asked grown-ups about getting other dice, well, none of us had ever seen such a thing. My childlike understanding was that I would literally have to go to TSR in Wisconsin to get these weird dice, which the grown-ups around me said didn't even exist. So I kind of forgot about the dice and skipped a lot of other rules that my reading level wasn't up to deciphering and adjust the combat rules from the Napoleonic minis game I knew.

“Roll a d6 [that is, a regular six-sided die], add bonuses for magic items, high roll wins. Gradually I worked other elements of the Napoleonic game into the mix, like using the cannon's grapeshot template I had made from twisted coat hangers and using that as a fireball explosion, but mostly we were making it up as we went, doing what seemed fair, or at least fun. Sometimes I would kill a friend's character in a trap, and that wasn't much fun. Other times we would have fun doing things like recreating the Watcher in the Water scene from LotR on the second level of my dungeon, or imagining a school for dragons on the third level.”

So to play the game, Rob fell back on the very Napoleonic miniatures rules that inspired D&D in the first place. The dice the original rules required were polyhedral dice, those platonic solids in every nerd’s basic toolkit: the pyramidal four-sider, the standard cube, the eight sider, the twelve sider, and, king of all, the twenty-sider, icosahedron, herald of a billion virtual dooms (ah, so that’s how you’re supposed to get this number from 1 to 20!). After first trying to use plain dice and then learning better but having to wait for the real thing, he made do with chits drawn out of a cup.

“The game was clear about the type of fun you were supposed to have, just not about how to get there,” according to Rob. “By the time I re-read the rules as an 11-year-old and figured out how D&D was really supposed to work, we'd been playing for a couple years using anything I could cobble together. I may have been younger than most, but I don't think I was the only person forced to cobble their own system together, and for a lot of people that also became part of the fun.”

As a middle-schooler, Jonathan heard rumors of D&D out of Augustana College in Illinois, where his dad was an English professor. He gleaned that it involved players standing in a circle pretending to be monsters and treasure. Odd, he thought, that college students would like that kind of thing. When his dad introduced him to a group playing in the student union building, strange dice on the table, character sheets and books piled around, the game hit him with nerd lust.

“So you actually had an example of play,” I said. “Did you get it on your own after that?”

“No, my dad introduced me to a guy who taught me.”

Then Jonathan and Rob told me how another important roleplaying game designer, Ray Winninger, came to D&D by way of the Deities and Demigods pamphlet. Ray gathered that you played the gods, and he and his friends battled orcs with the impunity of exterminators clearing out basement mice.

It’s not so much that the rules were poorly written; it wasn’t just that we didn’t know what we were doing, apparently Arneson and Gygax didn’t either. What was all this crap about movement in inches anyway if redrawing the map with one-inch squares was wrong? Back in the seventies, those guys had begun to create a new thing; it was not a miniatures game, not really. But they tried to make it look like it was, throwing in shoptalk without translation.

So none of us knew what we were doing, but was that a problem? Jonathan and Rob agreed that they took the incompleteness of the game as an invitation to develop it themselves.

Playing a Game by Telling a Story

D&D has been an activity largely defined by its fans. Veteran game designer Mons Johnson told me, “D&D had a strong high concept, but was always just a structure, a Christmas tree with no ornaments you had to decorate yourself.”

The storytelling element is key. If you’ve got players pretending to be heroes in a medievalish fantasy world, if you’ve got dice, and a dungeon master to tell the story, you’ve got D&D. Of course, Gary Gygax tried to get a lot more to stick to it, but struggled to draw lines between simulation and abstraction. On the one hand, he was fond of tables for interpreting dice rolls, not just combat tables for magic-users, clerics, fighter-types, and thieves, but tables to routinely check your characters for parasites and to diagnose mental ailments brought on by trauma or sorcery. On the other hand, he said in the original Dungeon Master’s Guide that “hit points,” the measure of damage a character could sustain, represented a mix of skill, luck, and divine favor more than physical toughness. Whereas wounds like broken bones weren’t, as he put it, “the stuff of high fantasy,” both trichinosis and trichophobia apparently were.

Most players I knew dispensed with the Parasitic Infestation table.

The Rise of the Modules

Though depending on the hard work and superior judgment of its audience, D&D was sold as if it were a finished consumer item and not a hobby kit, and it sold well under that pretense. By the early eighties, D&D’s parent company, TSR, had begun to tighten control of their brand, reining in the hobbyists who had evangelized and defined it, and wresting the company from Gygax himself. In 1982, TSR pulled the license they’d granted another game company, The Judges Guild, to produce D&D supplements, especially adventure packets known as modules. Several Judges Guild modules are still regarded as early classics, but their tone, design, and even interpretation of the game were at odds with the direction of TSR’s own. Also in 1982, Mayfair Games began producing their Role-Aids line of supplements, a move that caught the baleful notice of TSR lawyers, who obliged Mayfair to sign an agreement in 1984 restricting the way they referenced Dungeons & Dragons. At this time, TSR steadily upgraded the design of their modules and rulebooks. Between the slicker presentation and the brand policing, they sent the message that amateurs weren’t welcome to contribute.

“I started playing D&D in 1974 when it first came out and never bought a module,” Rob Heinsoo observed. “By the mid-eighties many kids didn’t even know you could create your own modules. Publishing a game that people had to reinvent meant there was a lot of creativity early on. It’s like early Christianity or Islam where there’s this charismatic moment, but then it has to be codified.”

TSR did more than codify, though. To extend Rob’s analogy, they routed the heretics who made it lively. Gary Gygax’s genius wasn’t in logical game design, writing, editing, or even business. Rather, it was in fusing the trappings of popular fantasy literature, board games, and miniatures games into a storytelling procedure just coherent enough to inspire players to make it better. TSR didn’t show awareness of this fact, and despite—maybe because of—superior production values and the game’s huge influence on literature, movies, and computer games, D&D fell into steady decline, until Wizards of the Coast bought it in 1997.

The Wizards Appear

Wizards itself originally formed out of a D&D group that tried to make a business selling roleplaying game supplements generic enough to avoid TSR’s censure. TSR didn’t bother them, but they ran afoul of a roleplaying game company called Palladium that sued them for referencing their trademarks, and the settlement in 1992 almost destroyed them before Wizards hit it big with Richard Garfield’s Magic: The Gathering card game the following year.

Flush with money from Magic, Wizards purchased TSR in 1997 and gained control of D&D. The Wizards founders keenly understood D&D’s hobbyist appeal, and sympathized with the amateurs that wanted to publicly add their own contributions. Wizards president Peter Adkison worked with Jonathan Tweet, Skaff Elias, Ryan Dancey, and many others, to develop the core D&D rules as an open-source product, called D20, after the common abbreviation for a twenty-sided die. (A friend of mine from the original Wizards cohort, founder Ken McGlothlen, states in my Facebook group, “The idea for D20 [and I'm not speaking from Jonathan's perspective, as he wasn't around at the time] was floated originally by Michael Cook as ‘Envoy’ in 1990, and he did quite a bit of work on it before politics shut it down. Michael doesn't get nearly enough credit….”)

Along with the Open Gaming License that defined the terms of its public use, D20 revitalized D&D as a hobby, and the supplements and systems built on the OGL, like the Pathfinder roleplaying system and Jonathan and Rob’s own 13th Age game, have thrived. Even The Judges Guild made a comeback.

Jonathan and his team reworked D&D from a fresh and logical perspective. Miniatures rules deserved a nod and would strengthen the role of, and therefore the market for, a D&D minis line. The first two editions of D&D were littered with inconsistencies. Monsters and player characters had their abilities defined on different, incompatible scales for no clear reason. The combat tables could be boiled down to a simple formula and modifiers. The armor class scale was goofy and unintuitive: the lower your armor class in the original rules, the harder you were to hit. And so on.

Arguably, something was lost in all this housecleaning, but much more was gained. Wizards didn’t sum up D&D, but their key ideas seem vindicated: the game is a hobby, and it worked largely despite many of its rules. D&D has some powerful hooks.

Mythic Archetypes Make a Comeback

A large part of the success of D&D was simply great timing. Fantasy literature was on the rise. D&D offered fans a chance to creatively engage with settings, monsters, and characters inspired by fantasy writers. These included Fritz Leiber, Robert E. Howard, Poul Anderson, Jack Vance, and Michael Moorcock, but the single greatest influence on the themes and trapping of the game was undoubtedly Tolkien. The final book in the The Lord of the Rings series, The Return of the King, had been released in 1955, but the books didn’t reach mainstream attention until the sixties, when college students in the United States made it popular.

Gygax and Arneson released D&D at a time when The Lord of the Rings was an established but still new phenomenon, and the animated movies based it and its prequel The Hobbit were in planning but still years away. The early editions of D&D made explicit reference to hobbits, ents, and balrogs, which were wholly Tolkien’s creations, and Gygax removed them only after the Tolkien estate threatened a lawsuit. He then reinstated hobbits as “halflings,” a name Tolkien had also used for them, but with less proprietary claim. Nearly all the characteristics of elves, halflings, dwarves, and orcs were standardized according to hints in Tolkien’s work, and are central to D&D. As a rule, D&D players before 1980 arrived at the game by way of Tolkien, including me, Rob, and Jonathan.2

Tolkien’s popularity is a separate study entirely, but in his obsessive fantasy world-building, with maps, made-up languages, monsters, and a divine pantheon, he provided the template for the Dungeon Master. Moreover, Tolkien drew extensively on northern European mythology. As Rob noted, “Outside of a few preparatory schools, hardly anyone has a classical education these days. D&D has been classical education for the masses.”

D&D owed Tolkien a huge debt but went far beyond his contribution in reviving the central myths of Western Civilization for popular consumption. Western culture is rife with images and linguistic artifacts from Celtic, Norse, Roman, and Greek mythology, but before D&D few people associated them all with each other. When I was a young kid in the early seventies, I puzzled over the Mobil gas-station logo. Why did a horse have wings? Between the Monster Manual and its sequels and the Deities and Demigods book, D&D appropriated and ranked just about every hero and creature that had ever popped up in a European myth or fairytale, creating a sort of memory palace for the bits of arcana scattered all around us.

Of course, bestiaries and mythic encyclopedias existed long before D&D, but the game assigned numeric attributes to creatures and magic items. The game set a standard for talking about goblins, kobolds, elves, and dragons. D&D made farflung monsters and magic cohere.

Getting the Jung of Things

Gygax’s project to normalize the discussion of monsters like dragons and orcs; adventuring classes; magic spells; and treasures mirrored an earlier project of Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung, who had been Sigmund Freud’s main disciple until he began to question Freud’s ideas. Jung set out to make common abstractions from world myths. He hit on the idea of the collective—that is, universal—unconscious and the archetypes.

The archetypes are a slippery concept and can’t be approached with too-literal a mindset, because they are glimpsed by their contents, which are changeable. Just like a drinking glass can hold and give shape to various materials, like water, sand, or pebbles, the archetypes are filled with human experience. For example, Jung identified one archetype he called the Shadow, which contains aspects of one’s personality that are incompatible with society, either because they’re outright evil or just arbitrarily forbidden. Other archetypes include the anima, which is the feminine aspect of a man; the animus, which is the masculine aspect of a woman; and the Mana, or “Wise Old Man,” that represents the collective unconscious itself.

In Jungian psychology there is a ranking of dream symbols, from personal to universal, but interpreting the symbols isn’t as simple as looking up their stats in the psychoanalytic version of the Monster Manual. They depend on context. A horse by itself doesn’t mean much, but when that horse is in a house, it may represent the vitality of the body. (One nice thing about Jungian psych is that it recognizes a subject’s authority over his own experience. While Freud could always counter objections to his diagnoses by claiming that the patient’s unconscious had merely repressed the truth, Jung tended to defer to the patient. If the patient wasn’t satisfied that Jung’s dream interpretation was correct, then neither was he.)

A test of the antiquity and universality of a symbol for Jung was its emotional quality. If it struck a person with religious awe or dread, if it had what Jung called a “numinous” quality, it might lie close to the heart of the human condition. Underground labyrinths are a classic dream symbol representing the unconscious, with the deeper levels inhabited by the most primitive and hazardous psychic forces. It’s maybe not so curious that the dungeon goes so well with the dragon and its treasure. The idea of sprawling underground catacombs, with greater foes and greater treasures the deeper you go, is very much a Jungian motif.

Jungian analysis and D&D range the same territory. Ideally, if not always in practice, a character is a vehicle for exploring one’s hopes and fears. Parodies of D&D on shows like Community and the IT Crowd recognize its group-therapy aspect—for example, to get over feeling alienated and depressed or to come to grips with a romantic breakup. According to Jungian psych, some symbols are more universal and powerful than others. By placing them together in a game, Gygax made it possible for older symbols to give the Midas touch to arbitrary new monsters, treasures, locales, and character classes. Like Jungian psychoanalysis, the game is an exercise in relating oneself to universal myths.

Warbands of the Dining Room Table

While Jungian psych is more my thing than Jonathan’s, he and I both share an interest in evolutionary psychology, which takes the view that our ancestral hunter-gatherer environment and tribal dynamics had a big impact on how the human mind evolved. We’re not true believers, but we think interesting hypotheses have come out of it.

I asked Jonathan about group dynamics from an evo-psych view, and he brought up the idea of D&D group as warband.

Getting the Psych Right

One of our closest primate relatives is the chimpanzee, and it’s violent and xenophobic, apparently by nature. Male chimpanzees forage as individuals but organize into bands for hunting and warfare. When they find a strange male chimp in what they regard to be their territory, they’ll cooperate to hold him down and beat him to death. (“Why the animosity?” I asked. Jonathan shrugged, and said, “They’re neighbors.”)3

"Chimps spontaneously form bands of three to five males and maybe a female, and they venture into enemy territory,” said Jonathan. “There they kill males they find and take possession of females. If young men like forming into marauding squads of bad-asses, that predilection goes way back. There may also be a connection to hunting and scavenging. A million years ago, bands of us fought predators for their kills. Today, we like to pretend we're roaming around fighting monsters for their loot.”

The chimpanzee warband is a functional group, not a friendship group. Chimps have their intergroup rivalries, and they set them aside to form a band. Similarly, men join warbands, either spontaneous primitive ones in neighborhood gangs or formally trained and coordinated military units. The male warband may well be in our blood. Again, these are functional, not friendship, groups: the friends don’t form the band; the band forms the friends.

"In many tribal societies, adolescent men go through shared, painful rites of passage,” Jonathan added. “These ordeals bind them together, and the adolescents become a cohort of warriors who will fight side by side for the rest of their lives. Maybe the pain we shared by mapping every inch of the dungeon had some sort of bonding effect."

In nearly every case that Jonathan, Rob, and I could think of, a D&D group had at least one member who wouldn’t normally spend time with the others. Also, D&D games incorporated men of very different ages. A black college student played with Jonathan’s group of white middle-school kids, but he wasn’t a social outcast among his peers and certainly didn’t hang with the players outside the game. My groups brought together neighborhood kids I didn’t otherwise spend time with, and in high school I was briefly part of a group that incorporated nerds, stoners, and jocks alike who had little to do with each other outside the game.

In the ancestral environment, adolescent men would have been initiated into mixed-aged warbands to hunt animals or raid other tribes. It’s during that same age that boys first play D&D. The appeal of slaying monsters to take their treasure may correspond to chasing predators off their kill. In his book An Instinct for Dragons, anthropologist David E. Jones posits that dragons are an amalgam of the raptor, snake, and cat predators that threatened our ancestors. Jonathan thinks the idea is interesting, but doesn’t credit it much. Dragons might basically be snakes.

To say that the warband fits male psychology isn’t to say it commands a dedicated mental circuit. The warband may be a side effect of more generalized brain functions. In either case, I think Jonathan’s on to something. However, we brought this idea up to Richard Garfield, the American game designer who created Magic: The Gathering, and he wasn’t so sure.

“I think that’s a common property of games. It doesn’t apply only to D&D. You could say the same of bridge or chess clubs.”

While D&D is primarily a male activity, a lot of women play too. I asked my daughter about this. What about the idea that going into “dark and nasty places with a group in order to kill dark and nasty things,” as Jonathan puts it, is really a boy thing?

My daughter Alyx commented that she gets that, but thinks it’s a matter of degree. In babysitting young boys and girls, she sees boys’ tendency to be more aggressive and their need to channel it. On the other hand, she likes the same things about D&D that boys do, the idea of hunting monsters and gaining treasure. She especially likes the storytelling aspect and using the rules as a springboard to improvisation, having to keep on her toes when the dice produce an unexpected result. She also says that the fantasy allows her to work out her real-world anxieties by “giving them a different texturing.”

“Like my elf character is concerned about the environment; she fights those who ruin and corrupt nature,” Alyx said.

Compared to all our great-ape cousins except gibbons, humans have little sexual dimorphism, which indicates we have undergone similar selective pressures. A warband brain circuit or circuits may exist only in men, may include both men and women, or may, like physical strength, involve an overlapping but separate distribution. Alyx claims that one thing that attracts girls like her to D&D is that due to magic and special character-class powers, girls aren’t limited by strength or size. They do the same things boys do.

Who Is the Player and Who Is the Master?

About a month ago, I told Jonathan that I was interested in making a disciplined study of D&D. He pointed me to his acquaintance Jon Peterson’s Playing at the World, an exhaustive history of the early game and its influences. Meanwhile, former Wizards project manager Mike Davis pointed me to Characteristics of Games by former Wizards R&D staffers Richard Garfield, Robert Gutschera, and Skaff Elias. Peterson’s book demonstrates that both historical board and miniatures games and fantasy literature inspired D&D. The other book, Characteristics of Games, defines the mechanics of all games, including sports and computer games, and outlines the balance of luck, skill, and human factors among them. Both books are excellent, though Characteristics holds the most general interest.

Characteristics of Games collects and standardizes many terms used by expert designers. One of its key dichotomies is agential versus systemic elements. A game, as the book stresses, is much more than just its rules system. A game is an activity that takes place among players, and involves their quirks and larger goals. The rules are systemic; the human element is agential. (The book states, “One can think of ‘agential’ as a more euphonic version of ‘player-ential.’ ”) D&D is heavily agential. The group dynamics of the game within its systemic, or game-defined, roles are maybe its most important feature.

Playing at the World reveals that the role of Dungeon Master grew out the referee role in miniatures games. Due to the variability of the miniatures battlefields, often involving ad hoc three-dimensional terrain, disputes arise about how to apply rules, and a referee is called in to resolve them. A Dungeon Master began in this role. In the proto-D&D games conducted by Dave Arneson players assumed the roles of heroes on one side and monsters on the other and played against each other to win. The referee kept them honest. Eventually, Arneson conducted an odd experiment and assumed the role of both monsters and the referee at the same time, thus inventing the Dungeon Master.

The DM Breaks the Game

The Dungeon Master role is a powerful discovery. Once you set up a referee in the angsty position of representing a side and yet striving to be impartial, you have, by received wisdom, broken your game.4 But it’s really only a conflict of interest if the referee wants to win. The DM’s goal is not winning but to facilitate a story and show everyone a fun time.

When I played the DM as a kid, I had a naïve faith in the rules to create a story; I tried to submit to the dice as much as possible. Like an author friend of mine who consults the I Ching to tell his fortune, I half-convinced myself that the story produced by rolling dice and consulting tables had an objective reality. There’s a line by Gary Gygax that Wizards founder Ken McGlothlen likes to quote: “The secret we should never let the gamemasters know is that they don't need any rules.”

The no-winner side effect of the DM function is probably D&D’s most-touted feature, but who can take credit for it? From a remove, the DM idea looks pretty creative, but then so does, say, the design of a butterfly or fish. An animal, according to the theory of evolution, embodies a series of accidents that resulted in the appearance of conscious design. And that’s how things seemed to work with the Dungeon Master and other player roles in D&D, an activity more discovered than created.5

What principles of human social interaction did D&D discover, though? Is it surprising that anyone would want to lead a group in creating a story? Recall that D&D initially spread on paper as a rough concept and people had to be taught how to play. Both learning how to be a DM and fulfilling the role mirrored the ancient oral tradition. A DM is an entertainer and a transmitter of culture, epitomizing the storyteller and shaman, prestigious tribal roles that are probably as old as language itself. But what about the players? Do they fill tribal roles?

Specialists and Utility Players

As a young kid, I’d join the boys in the neighborhood in their game of army or Cowboys and Indians, which combined hide-and-seek with imaginary gunplay. Determining who got shot and therefore was out of the game could start fights, and was resolved more by intimidation and wheedling than logic, although it probably didn’t seem that way to the strongest and most popular kid. Through Cowboys and Indians, boys negotiate their place in the gang as leader, lieutenants, and spear carriers. This is taxing, especially to introverts. Wouldn't it be great if you could just slip into a comfortable role that your group would immediately acknowledge as valued? A good adventure needs a range of interesting specialties: a thief, a fighter, and a spellcaster like a priest or wizard. It doesn’t need a spear carrier, nor even a leader6, the Dungeon Master not being technically part of the group. Everyone is highly valued, at least on a systemic level. Unlike the Cowboys and Indians game, you don’t get into arguments about what you accomplished because the dice resolve those uncertainties, and in addition to dedicated powers, each character type has its own dice bonuses, like the hiding bonus for thieves and combat bonus for a fighter.

I talked to Magic: The Gathering designer Richard Garfield about this, and he said that he didn’t see the specialization as a unique feature of Dungeons & Dragons.

“I wouldn’t put D&D on a separate level from sports in this regard,” Richard said. “Anytime you have a team activity, you have a tendency to create specialized roles. I think you have a point in that D&D offers people who don’t participate in sports the opportunity to explore the sports dynamic.”

My zoologist friend Dr. Rob Furey observes that sports and D&D, beyond being games, are play activities, which many species engage in. Play activities allow animals to practice skills directly applicable to real life, and cooperation and specialization are important concerns of human beings.

Richard and I discussed the aspect of having your role handed to you and supported by the rules rather than your own ability. Richard pointed out that you do exercise skill.

“Not everyone’s equally suited to play all characters,” he said. “The guy who plays a cleric like a fighter, for instance, and is not making good use of his spells.”

Even given that a player’s character might not be a good personal fit, D&D allows players to assume a useful role with minimal negotiation. That’s a significant time and stress saver, and allows you to get on with the story. Also, after you’ve overcome initial self-consciousness, it allows you, ironically, to be more yourself, because your usual persona isn’t at stake (the Persona, or mask that you present to the world, happens to be one of the Jungian archetypes).

The Heuristics of Growing Up

From its universal symbols to the roles of characters and Dungeon Master, D&D presents a framework within which a meaningful and surprising story might grow. But it doesn’t always work. Sometimes you open the wardrobe and go into Narnia; sometimes you find the gate is closed. And just as with going to Narnia, D&D gets harder when you’re no longer a kid.

So why is this? Is it simply that you have to stop toying with the possibilities and take on a serious role in life, to contribute to society, to make money, to raise a family? D&D’s a childish pursuit with limited real strategy potential, and you outgrow it. Right?

Not necessarily. The fact you’ve stopped learning how to make it better doesn’t mean there isn’t more to learn.

D&D is a hugely ambitious project. It’s easy to parody, because it’s easy to see the level at which it becomes ridiculous, and not so easy to see its possibilities. Its core strength of being a no-winner game is also its greatest weakness in this regard. The reason that chess is widely known as a deep, intellectual game is that chess experts beat amateurs. A beginner has effectively no chance to beat an expert. You can’t argue with that. Most people think winning at chess is a matter of intelligence and being able to plan ahead. Intelligence is a factor, but the difference between a poor chess beginner and a solid player is that the solid player has climbed further up the “heuristics tree.”

A heuristic is a general strategy, or rule of thumb, for getting ahead in a game, like the opening moves in chess or the guidelines for hitting and standing in blackjack. They are not the rules; they guide you in how to exploit the rules. Characteristics of Games defines “climbing the heuristics tree” as “learning successively better and more sophisticated heuristics for a given game.”

The book distinguishes between positional and directional heuristics. Positional heuristics give you a sense of how you’re doing in the game. Directional heuristics guide you in making your move. In D&D, a positional heuristic in a fight might be your remaining hit points. A directional heuristic might be to run from the fight when your hit points are near the upper range of a monster’s damage potential. Those with no awareness of a game’s directional heuristics are out to sea; they’re playing a random game. Players perceive different heuristics at different skill levels. Those with only passing familiarity with D&D notice only its simplest mechanics, and don’t appreciate how much the players and DM can negotiate a higher level of play.

The Imprisoned Halfling's Dilemma

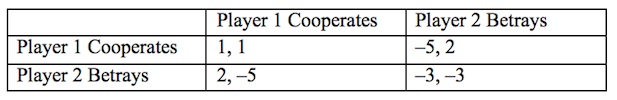

Discovering a game’s heuristics through play comprises a lot of a game’s fun. But you can define game strategies mathematically too. Game theory was invented in the forties by mathematician John von Neumann, who applied it initially to economics, and it observes that games have best-strategy positions for rational players, called equilibria. Consider the theoretical game of prisoner’s dilemma, a staple of game theory. Prisoner’s dilemma can be described in different ways, but here’s the setup from Characteristics of Games. Two people rob a bank together, hide the money, and are independently caught. The police are trying to get each to rat out the other. Each has the option of staying quiet or squealing. If both players stay quiet, they go free and split the money, a mutual win. If one betrays the other and isn’t betrayed himself, he goes free and keeps all the money while his partner gets jail for five years. If each betrays the other, they both go to jail for three years. This is what the tradeoff matrix looks like, where one unit of money is equal to the opportunity cost of a year in jail:

In the absence of any other factors, the best strategy is betrayal, because it’s the position from which it doesn’t benefit you to unilaterally change. Whether you assume the other guy will stay quiet or squeal, you stand to gain the most (against cooperation) or suffer the least (against betrayal) by betraying. This equilibrium, where neither player can improve his situation by changing sides unilaterally, was identified by mathematician John Nash, of A Beautiful Mind fame. To model a real-world scenario and possibly get a different equilibrium point, you need to broaden the picture, say by assuming communication over a series of games and introducing a small chance of spontaneous cooperation.

Prisoner’s dilemma shows mathematically that a rational solution to a strategic problem may not be the optimal solution. If the goal is to achieve the best outcome for both players, then cooperation beats betrayal. Adding up the values in each cell of the matrix, cooperation yields a 2. The other options yield no better than a –3.

A Proper Game Is Never Solved

If you’re just finding the most rational, or even optimal, strategy among a set of competing options, you’re not really playing a game but rather solving a puzzle. To make it a game, you need either an agential factor like political maneuvering or extra randomness, as supplied by dice, or both. What I’d call a “proper game” is never solved. When you’re a little kid, tic-tac-toe works as a proper game, but eventually, you solve it, and every game you play thereafter results in stalemate. Heuristics help you reliably exploit the equilibrium points in a game, but they don’t let you solve it. No human can solve chess, for instance. Heuristics just help you play at a higher level and survey the larger possibilities.

But if tic-tac-toe doesn’t qualify as a proper game when it’s solved, neither does Cowboys and Indians when no one can agree on the rules, which is most of the time. Again, we return to the role of the DM.

“You really do need a 'proper' two-sided [or more] game to have the game theory stuff or equilibrium strategy make much sense,” Skaff Elias noted to me in email. “The DM has way too much power to call him a side or player, and his 'strategy' would be to simply always win if he cared to.”

As I said before, if D&D is interpreted as DM-versus-players, it’s an unfair game. Game theory really doesn't apply. The same is true if the DM tries to take the players’ side. But unless the DM runs the adventure like a board game—like I attempted to do when I first tried it – he can’t be impartial either. Even if you wanted a DM to act like a computer, you’d have to program a rule to cover every situation, but that’s impossible. Therefore, either the DM improvises or he limits the scope of the game.

Actually, I think limiting D&D to board-game scope—as I did when I first played it—is a valid way to start out. Even if a DM is comfortable with storytelling, the group might not be. They may need to warm up with more structure. To approach D&D like a board game, a DM needs to break it down, to identify what Characteristics of Games calls the game’s atom, or basic unit of gameplay, which is just enough activity so that players “feel like they’ve really played some of the game,” like two possessions in football. A D&D atom is probably an encounter situation with a monster or trap and ends when the monster or trap is overcome. Next, he needs to identify the variables involved and not allow for much improvisation. Combat is a frequent type of conflict in the game because it’s the easiest to quantify, and most of the D&D rules concern its variables, namely armor classes, hit points, and various standard bonuses that accrue to strength and dexterity.

Improvising and the Old Reliables

Reliable encounter and combat heuristics have evolved for D&D. If you’ve got the advantage of surprise, you want to set up an ambush rather than reveal yourself. You want to use missiles if you can instead of charging in. You want to position the thief to creep in for a sneak attack. You want healers in position to heal. You want to target enemy spellcasters with a silence spell, which drastically reduces the spells they can cast back at you. You may want to spread oil on the ground that you can light to cover a retreat or injure and expose your foes.8

Beginners have fun learning these proven cooperative strategies, or solving explicit puzzles, like a sphinx’s riddle or a murder mystery from prepared clues. But at this level, D&D grows stale, and if this were all the game had to offer, it wouldn’t be as popular.

When I was in middle school playing basic-set D&D, I had a naïve belief that the advanced rules, which covered the higher character levels, would show me how to climb the game’s heuristics tree (and maybe give me the key to storytelling itself). The basic rules teased you with narrative possibilities, but the ones they actually described were limited: hitting an opponent, searching for secret doors, checking for traps, picking pockets, making saving throws, choosing spells. They listed only a few magic items and other treasures, weapon and armor types, spells, and character classes. All the most popular commercial modules needed the advanced rules, which covered the higher-level characters and monsters; and the scenarios they described seemed rich with new possibilities. Surely Advanced Dungeons & Dragons would offer more “proper-game” strategies.

But it really didn’t. Aside from a few actual game rules, like to determine when monsters would cut and run, it mostly just gave you more monsters, weapons, armor, magic, and character types. These were important to D&D’s function as classical education and to offering the community more things to talk about, but they didn’t represent an advance in gameplay potential. The new variables, like getting worms from bad inn food, didn’t really improve on just making stuff up, and proved the futility of trying to circumscribe the possibilities. In an honest if not too business-savvy move, Wizards dropped the pretense of an “advanced” set when they took over D&D.

To play D&D at a truly advanced level, that is, to tell a unique story, requires improvisation. The dungeon setting, with its constrained environment, and the rules written to it are scaffolding to get things started. D&D improves on Cowboys and Indians by setting a structure for players and the DM to create and abide by their own rules. When the players have a naïve faith that rules exist for all contingencies, they’re more likely to accept the DM’s pronouncements, which seems to me one good reason that the Dungeon Master’s Guide includes most of the game rules, and in theory if not practice, these aren’t known to the players. It’s also a reason for the DM’s screen—which hides not only dice rolls, but also the times the DM interprets them without consulting any rules.

The Stages of the Quest

In moving beyond the board game, the expert DM places encounters in a meaningful context and helps players set both wider proximate goals and ultimate goals. For instance, with the ultimate goal of defeating a powerful dragon, a party’s first larger goal might be to earn enough money and experience to leave the safety of a town—as in the old computer game Darklands, which I think is a good example of a computer game that can offer inspiration for D&D adventures.

Since the computer fills the role of Dungeon Master in Darklands, a given strategy might yield a dependable result, and therefore be a true heuristic. One heuristic in Darklands was to get ambushed by thieves and steal from them, sell their goods by day, and then purchase increasingly better armor and weapons. You needed to keep money on hand in case you ran into the watch. If you didn’t bribe them, they’d strip you of all your possessions; if you fought them, you might bring the whole town guard on you. So: hunt thieves, retreat to the inn, sell the loot, bribe the guards, repeat.

Here’s an example of a D&D adventure mirroring the Darklands starter heuristic:

- The party goes into the wilderness and is outmatched in a fight with wandering monsters. The DM gives them the chance to make a tactical retreat. They are chased to town.

- They stumble through the gates and are approached by a solicitous stranger who tells them to meet him at the docks to get healing.

- Attentive to hints, the party instead pays money they can barely afford and gets healing elsewhere, another kind of tactical retreat. They are so broke they cannot even stay in the inn.

- They make the rendezvous prepared. They meet and overcome an ambush, gaining experience and loot. Hah, an advance. They go to the inn and nurse their wounds, secure from thieves.

- At the inn, the party learns that the thieves they killed are part of a larger network, and they decide to clean it up (for altruistic reasons, of course).

- After a few interesting tactical battles, the DM introduces the crooked town guards, who confront the party on its way back to the inn and demand a bribe for breaking curfew. They’re outmatched, so they pay, which is another kind of tactical retreat. (If they choose otherwise, they may learn a hard lesson.)

- The party fights thieves and small monsters and gets enough experience, magic, and equipment to challenge the crooked watch.

- After defeating the watch, the party heads into the countryside and defeats the monsters that first defeated them.

Out of the Chaos, Magic Strikes

In a computer game, this progression would be scripted and almost inevitable, but the possibilities at each point are much more varied in D&D, or at least they should be. The general heuristic to be found would therefore be more general, say to identify safe zones, retreat from larger foes, and save enough money for bribes. At each of these points, the adventure could take a very different path from the one I described. It’s up to the DM to recognize the dramatic possibilities unfolding. A so-called sandbox adventure, as opposed to a canned-story adventure, would place the monsters in the wilderness, describe the town watch as crooked, and define a network of thieves; the possibilities from there are limitless, and the party would need to set their own goals.9

Wizards of the Coast founder Ken McGlothlen sums up the situation:

“Player characters will make unexpected choices; a good gamemaster will find that non-player characters [that is, those run by the DM] will make unexpected choices as well, just as [novel and short story] authors will occasionally find their characters doing something different than what those authors had intended. The gamemaster must plan ahead for contingencies, but accept that some contingencies will never happen, and unexpected ones will. But in a good campaign, the players will never, ever feel railroaded.”

A DM learns storytelling outside of the game, in playing computer games; in reading widely; in dreaming up his own adventures, or pondering how to merge third-party ones into his campaign. When he brings his group together to create a story, there’s a fair chance the whole exercise will devolve into chaos, that no magic will happen at all.

But sometimes it does.

Notes:

1. In the first draft of this article, I wrote that Rob Heinsoo had purchased the white-box set of original D&D. Nooo, he had the original original brown woodgrain-patterned set. I am duly chastened. I didn’t even know that there was an edition before the white-box set.

2. Ken McGlothlen: “Believe it or not, not true of Peter, myself, and a few others in the Walla Walla crowd. We were playing B1 [the first basic-set module, “Descent into the Unknown”] before we read Tolkien. (For me, it was a close call; I think I picked up The Hobbit a few weeks afterward.)”

3. Rob Furey noted that animals do not normally cross territories to kill neighbors, and this applies to chimps. It is in their fitness interest to respect territorial boundaries, and this warfare involves chimps encountering strangers, not neighbors (but that’s what Jonathan initially said, and he was making a joke with the latter comment). In her book In the Shadow of Man Jane Goodall observed that chimp gang murder is a rare occurrence. Chimps more frequently team up to hunt prey, which include other large primates, like colobus monkeys.

4. I ran this idea by Richard Garfield, but he disagreed that having a player adjudicate the rules meant that a game couldn’t be about winning. He pointed out that there are miniatures games where the player who knows the rules best interprets them for the others and strives to be impartial. Of course, the DM has rules the player doesn’t, has to make up new ones on the fly, and keeps the statistics of the monsters he represents secret from the players, so if the idea doesn’t hold generally, I think it does for D&D.

5. Evolution’s happy accidents occur within the framework of natural laws. The question of whether nature has any teleology, that is, “far logic” directed by a divine will, is a philosophical, not scientific, one. Tolkien, who, as I’ve said, provided the obsessive-fantasist template for the Dungeon Master, very much believed in divine teleology. He was a Catholic who considered himself a “demi-creator” exercising a divine faculty (or “a talent on loan from God” to quote Rush Limbaugh’s self-assessment). Tolkien found his own path to God through his work as well as his religion. The idea of Dungeon Mastering or D&D being a Satanic activity, as fundamentalist Christian preachers claimed during the eighties, probably would have struck him as odd. On the other hand, being a bit of a coot who said college students dressing up as his characters “were drunk on art,” he might also have dismissed D&D as silly. Tolkien died the year before D&D was released.

6. In the first versions of D&D there was the concept of a player leader who would report group decisions to the Dungeon Master, a role known as the caller, but Jonathan identified it as an unnecessary misstep.

7. I asked Skaff Elias, one of the authors of Characteristics of Games, how heuristics relate to game equilibria, and he said, “I don't actually think heuristics need to exploit purely rational strategies. For example a heuristic one might employ is that you know you feel uncomfortable roleplaying a murdering, thieving, bastard, so you pick a good character, or even a paladin.

“You may know that you are really good at talking around the table, so a heuristic might be to put stat puts in Charisma, pick a Charisma race [like elf], or a Charisma-based class [like a paladin or bard] so that your natural talents and inclinations and enjoyment match the stats. There isn't any mechanical benefit, so it's not 'rational' (and may even be the reverse) but your heuristic for personal and table enjoyment is one of 'irrational' benefit to you.”

8. In his online editorial for Dragon Magazine “Achieving Equilibrium” Steve Winter, addressing game theory, briefly describes various strategies for party-cooperation:

http://www.wizards.com/dnd/article.aspx?x=dnd/dred/2010November

9. Confounded by maps and combat tables and willful players, it’s very easy to lose sight of the primary storytelling goal. I’ve already explained how when TSR policed the D&D brand it ended that “charismatic moment,” as Rob Heinsoo put it. As part of their effort to bring D&D to a mass audience, it seems they hedged their bets against hit-or-miss storytelling with modules that had a foregone conclusion.

A month ago, I stumbled upon Loren Rosson’s Busybody blog and its articles “Classic D&D Modules Ranked” and “Looking Back on Dungeons and Dragons”; both identify a shift in the mid-eighties from sandbox to story-path design, and a corresponding progression from D&D’s Golden Age to a Bronze Age. The publication of adventures that encouraged DMs to behave like computers was a hallmark of D&D’s decline.

Classic D&D Modules Ranked: http://lorenrosson.blogspot.com/2013/02/classic-d-modules-ranked.html.

Looking Back on Dungeons and Dragons: http://lorenrosson.blogspot.com/2011/09/looking-back-on-dungeons-and-dragons.html.

Loren’s articles owe a debt to other articles at Grognardia, which he links to.

---

Thanks to Jonathan Tweet, Rob Heinsoo, Ken McGlothlen, Mike Davis, Mons Johnson, Skaff Elias, Rob Furey, and Richard Garfield for their discussions that informed this article. Thanks to Jim Lin for hosting the Super Bowl party where many of these conversations took place.

Dungeons & Dragons, D&D, and Wizards of the Coast are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast LLC.

Copyright © 2014 by Bob Kruger

Bob Kruger is the president of ElectricStory.com, a software-development and ebook-publishing company. He's worked as a writer and editor on tabletop and computer games for several companies, including Wizards of the Coast and Microsoft.