We begin a multipart series on training for war by retired Army lieutenant colonel Tom Kratman, creator of the popular Carrera military science fiction series, with latest entry Come and Take Them. Does it seem as if the United States land armed forces have lately been training to be cadres of world policemen and social workers rather than soldiers prepared to win a war? Here Kratman distills lessons from years as a commanding officer in the U.S. Army, where he retired a colonel. Kratman’s argument: an army is for winning wars. And to win wars, you have to train men (and some women) to be warriors.

by Tom Kratman

Dedication: For Lieutenants Bill White, Lee van Arsdale, Mike Smith, Terry Jones, Jorge Garcia, Ken Carter, Steve Reynolds, Rich Hayes, Tom Dubois, Phil Helbling, Steve Natschke, Jaime Bonano, Scott Fitzenreiter, Mike Cook, Scott Brown, Chad Snyder, and Tom Matte

It’s hard to serve two masters, or two audiences, with a single paper. I’m going to give it a try, anyway, because the subject matters to most of the things I care about, in this case my army (and her sister services), hence my country, and (this being the other master) my current job, which is writing science fiction, hence my family. Interestingly enough, while one might normally think of military training in science fiction as totally at odds with military training in life – and it often is – I’ve seen at least as much fantasy and wish fulfillment in Army training as I have in some science fiction.

Then, too, I’ve been with an army that had just come out of a losing counter-insurgency campaign. Leaving aside the racial tensions, which were, at the private soldier level, amazingly ferocious, what was perhaps still worse was the company grade leaderships’ almost complete lack of understanding of our primary mission, which was how to train for the next war, or any conventional war. I can’t fault them for their devotion to duty, nor for their character, which was properly hard and harsh. But, when the Army and Marine Corps outside of Vietnam had become little but replacement depots for Vietnam, when that same leadership had been given nearly back to back tours there, interrupted only by short tours in dysfunctional units, when large chunks of the NCO Corps, which was even more put upon than the Officer Corps, left en masse, the ones remaining could hardly be criticized for not learning something the Army and Corps either just weren’t teaching or had spent a decade teaching the opposite of.

We trained hard, to be sure, miles on thousands of miles of marching with heavy packs (where “heavy” could and often did mean more than body weight), and still more awkward loads, alternatively freezing and roasting, bleeding and blistering. And doing not very much, really. As a character development tool the program had much to recommend it. As a training regimen, it left something to be desired.

“Left something to be desired?” Ummm…Kratman, old boy, just what exactly?

And awayyyy we go! But ere we do…

Caveat One: Most of what follows is non-doctrinal; it’s either just me, my approach, or the approaches of some other good military trainers from whom I learned a great deal. Some of this will be presented as axioms, some as vignettes, and some as illustration or speculation. Rather than say, “I did this,” or “Carter did that,” or “Smith thought this was a good idea,” or “White used to push this” or “van Arsdale suggested that,” the vignettes will be presented in the person of Private, Corporal, Sergeant, Lieutenant, Captain, Major, and Colonel Hamilton. Why him? Easy; Hamilton was one of my more likeable characters in my books. There’s a little of all of those in Hamilton, anyway, plus quite a few others.

Caveat Two: It would be nice to be able to say that everything here will apply as much to women as to men. Sadly, I’d be lying if I said I believed that. I don’t. I do believe that it might, if we approached the subject of women in combat with half a grain of sense (see, e.g., my previous article for Baen, The Amazon’s Right Breast, as well as my novel, The Amazon Legion). But c’mon, that’s not going to happen, not with the PC lunatics having control of the keys to the asylum. What I rather expect to happen, though, is that woman are going to volunteer to stay away from combat arms in huge and overwhelming numbers, that most of those very few who do go combat arms will be – shall we say, charitably – a bit on the masculine side, and that they might well become just one of the guys, with as much interest in, say, chasing girls are any male grunt, ever.

Caveat Three: Eventually, Inshallah, I intend to turn this into a book. I retain the right to change the number and numbers of the axioms, vignettes, and rules, or any other thing I damned well feel like, at that time, and said book will be the definitive edition. Until then, this will have to do.

I

Axiom One: The functions of training, the reasons we train, and all training can do for us, boil down to five things: Skill Training, Conditioning, Development, Selection, and Testing of Doctrine and Equipment.

The armed forces have a serious doctrinal lack when it comes to explaining why we train and how we do. Since they can’t articulate things like, “No, Doctor, Ranger School sucks in the way it does because we are conditioning and selecting, not merely teaching skills,” we get changes demanded from unqualified amd ignorant people, with credentials that bear no particular relationship to train for war.

I’ve spent, by the way, a number of decades since I first floated this axiom around, looking for a valid argument against it from anyone entitled to an opinion. I still haven’t gotten one, beyond the merest quibble. Every practicing trainer would probably recognize these as valid, even if they wouldn’t necessarily articulate them in exactly the same way.

The five functions should not be looked at as things that can be added up, to come to an approximation of a unit’s or individual’s training status. To even hope to do that you would have to be able to measure some immeasurables. Forget it; all the really important things can’t be measured, while all the really measurable things aren’t very important.

But if you could measure everything, trying to add their values together would still be the wrong way to look at it. After all, a soldier or a battalion, be they ever so skilled, are still worthless if they lack the courage to stand in line of battle, or to press the assault home. Instead, the proper way to look at them would be as things that must be multiplied by each other, with any factor being a zero causing the total to be worth zero, even if one approached infinity. Of course, again, since most of these are anywhere from difficult to impossible to measure, you’re not going to get a true value. The important thing to remember is that a zero in one is a zero overall, and even a serious weakness is one means weakness overall.

It’s also worth remembering that there is crossover. Better shooting ability, a skill, requires a degree of physical conditioning, but also conditions greater confidence, for example. Greater confidence develops greater trust and unit cohesion. I will treat these functions as distinct, for the most part, the better to illustrate them. But they are actually much fuzzier, with much more crossover, than that. They also apply in different ways at different levels, while some are appropriate to leaders, not so key to followers, and still others are collective, applying not just to everyone but to everyone in a unit together.

Axiom Two: Skill Training is the easiest.

Skill training is pretty obvious stuff: shoot, move, communicate, repair, account for, manage, request, fill out the form, clean it…there are thousands of tasks, but under a thousand for any given MOS (Military Occupational Specialty, that’s “job” for you non-cognoscenti). If in doubt, there are manuals to tell one how to do everything. A man or woman of average intelligence could learn to do most of them, and some could probably be done by a docile chimpanzee. Even fairly poor armies can do a fair job at skill training. They may not, of course, but they can, if only by sending people off to better armies to be trained. Of the five functions, skill training is the easiest, hence not necessarily the most important, for any given set of skills.

Among the reasons skill training is the easiest is that almost all skills are pretty measurable: hit the target, prepare and send the proper call for fire to the mortars or artillery, do the recon, write the operations order, analyze the map with regard to the enemy, camouflage the position so it cannot be seen from in front, drive the track without wrecking it, blow up X. Etc. Etc. Etc. You usually know when your troops have a skill down as good enough. You can tell when you’ve reached the point of diminishing returns, the point at which trying to get the task which must be done in thirty seconds done in twenty-nine just isn’t worth it, given how much else there is to do.

Axiom Three: Conditioning refers to the molding of non-conscious, instinctive, or non-intellectual characteristics, and the body. It is hard, not least because the mental and emotional aspects of it are nearly impossible to measure, objectively.

Science fiction often touches on conditioning, and sometimes with a certain amount of insight, albeit generally of the negative kind or by omission. Think here, Warren Peace in the late Bob Shaw’s book, Who Goes Here. Or Keith Laumer’s Boloverse. What do those two have in common? That the minds of the combatants can be directly programmed, or obedience unto death can be directly programed, easily and reliably, thus obviating the time consuming and incredibly iffy task of conditioning the combatants directly. Somewhat similarly, John Scalzi’s Old Man’s War provides artificial bodies tuned to perfection, thus eliminating the need to train those bodies.

In other words, no, we can’t do any of those things, now, and must rely on more traditional methods which are, again, iffy. They will remain iffy, too, for the foreseeable future. The trainer has to do the best he can, even knowing that he’ll never know for certain if that best was good enough.

So what do we condition for? We condition for group solidarity and for an innate sense of right and wrong or, maybe better said, to uphold the innate sense of right and wrong the troops bring to the colors. We condition for courage (even though we also develop courage) for, as Aristotle observed, we become brave by performing brave acts. In practice, that means that by overcoming fear once, and then again and yet again, we acquire the habit of overcoming fear and we acquire the non-conscious presumption that we can overcome fear without necessarily having to think about it very much. You might say that, since fear is an emotion, we combat it emotionally.

There are also physical skills that fall under conditioning. For example, shooting a rifle; we drill getting into firing position, the (formerly eight, last I checked three) steady hold factors, so they are done automatically, without thought.

That short list hardly touches on the subject of positive conditioning. Suffice to say that if something desirable in human character is non-intellectual or emotional or physical, we will for the most part work on conditioning it. And, if we have two brain cells to run together, we’ll realize how uncertain is our success, and how likely it may be that the troops, being human, are simply faking it, for anything non-physical and possibly even for the physical. Conditioned responses – conditioned in peace – to do things dangerous or unpleasant in war, will always be problematic.

Another area of conditioning, one highly pervasive in most western armies and in the Russian Army, involves battle drill. This, however, is a subject worthy of its own entry, below.

Conditioning is not only conditioning for something, it is also conditioning against something. For example, modern Outward Bound began life when it was noticed that young British sailors, with their ships torpedoed and sunk from beneath them, would very often simply give up and die in circumstances where they could have saved their own lives fairly easily. Why? Because they’d never been exposed to hardship and took even fairly mild hardship as too much to deal with. Outward Bound, among other things, conditioned sailors against giving up to hardship so easily, by exposing them to hardship. It saved lives, for a certainty. And, if it cannot be said that Outward Bound won the war, it can be said that it helped.

Vignette One: Even a goddamned horse knows enough to come in out of the rain.

Fort Campbell, Kentucky, late 1975.

The troops – they were a mortar section, rather badly understrength – staggered along the ochre-hued firebreak under painful, exhausting, and demoralizing loads. The least burdened of them was still humping well over a hundred pounds, and some of the more heavily laden bore half again more than that. They were soaked from the outside by rain, from the inside by sweat. There were no vehicles; this was the middle of the gas crunch when enough gasoline was simply not to be had. Worse, it was raining, that miserable Fort Campbell rain that came down lightly but steadily all day, then turned freezing at night. Worse than that, the mortars were last in order of march, meaning that a hundred and fifty-odd grunts had tenderized the dirt of the firebreak for them, turning it into a knee deep morass.

“Even a goddamned horse,” says Spec-4 Shipley, who, like the rest, has been transformed into a two legged pack mule, “has sense enough to come in out of the rain.” Shipley’s voice carries and is met by a chorus of approving grunts, spiced with a few poignant curses at the idiots in charge who don’t have sense enough to get them in out of the rain.

Private Hamilton isn’t so sure. He’s at least as miserable as anyone else. But the question in his mind is Kipling’s, “Knowledge unto occasion, at the first far view of death?” In other words, Ship, do you really think we’d do this in war, without just falling apart, if we hadn’t gotten used to it in peace? I have my doubts. And we’re not, loads notwithstanding, horses.

Axiom Four: We develop more intellectual faculties – or moral faculties that require thought – needed by the soldiers and their leaders.

Development is probably not as hard or iffy as conditioning, in the sense that, at least, the truth can be known, success can be, to some degree, validly measured. Still, it remains harder than skill training, and it is time consuming. It is mostly about leadership, yet not entirely, except insofar as every man under fire must often lead himself, make himself do some things he’d really rather not. That, and insofar as the moral echo of troops who have been well developed can sometimes reverberate in their leaders, giving those leaders a little more support in doing their jobs.

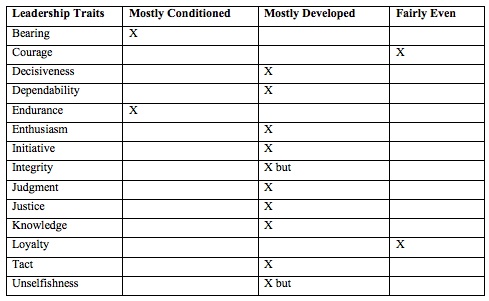

All the services share the same fourteen leadership traits. For the most part, we try to develop these in all the troops, at all ranks. Some we condition. And some partake of both. Feel free to argue with the categorization of the list below; I toss it up more for illustration than as prescription.

But how do you know how you’re doing? It’s a toughie, but something hard training can do is give you some hints.

Axiom Five: We subject the troops to hard, dirty, and dangerous training to select from among them.

What are we selecting for? We’re selecting leaders. We’re looking for people who might do well with special training or in particular jobs. (Sometimes that’s negative: “Schmidlap has proven worthless as a rifleman and machine gunner; let’s try him out as a driver.”) We want to identify and eliminate from service the stupid, the selfish, the treacherous, the unethical, the cowardly. If we’re from a culture like most of those in the Middle East (more on this later), we might try to select for people who can overcome their cultural conditioning and accept non-blood relations as quasi family.

Ranger School would be an excellent course for selection, though we really don’t use it for that. Especially valuable would be the peer evaluations which, unlike OERs and NCOERs, tend not to be inflated. The big thing though is that traditional Ranger School provides warlike levels of hardship and stress, which allows us to evaluate who does, and who does not, have what it takes to command in war.

Axiom Six: Without subjecting our equipment, and at least as importantly, our doctrine, to realistic testing, we can never identify our intellectual-doctrinal, moral, and materiel weaknesses, nor fix those.

That seems to me so self-evident that I’m loathe to add to it. That said, I probably have to. Why? Because that need to test doctrine and equipment to the point of failure comes with a price tag. Men die. Still, the adding can be done later, in a better place. Read on.

Copyright © 2013 by Tom Kratman

This series continues with “Training Part for War, Part Two.” Tom Kratman is a retired U.S. Army colonel and the author of many science fiction and military adventure novels including Carrera series entry Come and Take Them.