The Hymn of the Cannonball

7

The Hymn of the Cannonball

The Observatory of Cambridge in its memorable letter had treated the question from a purely astronomical point of view. The mechanical part still remained.

President Barbicane had, without loss of time, nominated a working committee of the Gun Club. The duty of this committee was to resolve the three grand questions of the cannon, the projectile, and the powder. It was composed of four members of great technical knowledge, Barbicane (with a casting vote in case of equality), General Morgan, Major Elphinstone, and J.T. Maston, to whom was confided the function of secretary. On the 8th of October the committee met at the house of President Barbicane, No. 3 Republican Street. The meeting was opened by the president himself.

“Gentlemen,” said he, “we have to resolve one of the most important problems in the whole of the noble science of gunnery. It might appear, perhaps, the most logical course to devote our first meeting to the discussion of the engine to be employed. Nevertheless, after mature consideration, it has appeared to me that the question of the projectile must take precedence of that of the cannon, and that the dimensions of the latter must necessarily depend on those of the former.”

“Suffer me to say a word,” here broke in J.T. Maston. Permission having been granted, “Gentlemen,” said he with an inspired accent, “our president is right in placing the question of the projectile above all others. The ball we are about to discharge at the Moon is our ambassador to her, and I wish to consider it from a moral point of view. The cannonball, gentlemen, to my mind, is the most magnificent manifestation of human power. If Providence has created the stars and the planets, man has called the cannonball into existence. Let Providence claim the swiftness of electricity and of light, of the stars, the comets, and the planets, of wind and sound—we claim to have invented the swiftness of the cannonball, a hundred times superior to that of the swiftest horses or railway train. How glorious will be the moment when, infinitely exceeding all hitherto attained velocities, we shall launch our new projectile with the rapidity of seven miles a second! Shall it not, gentlemen—shall it not be received up there with the honors due to a terrestrial ambassador?”

Overcome with emotion the orator sat down and applied himself to a huge plate of sandwiches before him.

“And now,” said Barbicane, “let us quit the domain of poetry and come direct to the question.”

“By all means,” replied the members, each with his mouth full of sandwich.

“The problem before us,” continued the president, “is how to communicate to a projectile a velocity of 12,000 yards per second. Let us at present examine the velocities hitherto attained. General Morgan will be able to enlighten us on this point.”

“And the more easily,” replied the general, “that during the war I was a member of the committee of experiments. I may say, then, that the 100-pounder Dahlgrens, which carried a distance of 5,000 yards, impressed upon their projectile an initial velocity of 500 yards a second. The Rodman Columbiad threw a shot weighing half a ton a distance of six miles, with a velocity of 800 yards per second—a result which Armstrong and Palisser have never obtained in England.”

“This,” replied Barbicane, “is, I believe, the maximum velocity ever attained?”

“It is so,” replied the general.

“Ah!” groaned J.T. Maston. “If my mortar had not burst—”

“Yes,” quietly replied Barbicane, “but it did burst. We must take, then, for our starting point, this velocity of 800 yards. We must increase it twenty-fold. Now, reserving for another discussion the means of producing this velocity, I will call your attention to the dimensions which it will be proper to assign to the shot. You understand that we have nothing to do here with projectiles weighing at most but half a ton.”

“Why not?” demanded the major.

“Because the shot,” quickly replied J.T. Maston, “must be big enough to attract the attention of the inhabitants of the Moon, if there are any?”

“Yes,” replied Barbicane, “and for another reason more important still.”

“What mean you?” asked the major.

“I mean that it is not enough to discharge a projectile, and then take no further notice of it; we must follow it throughout its course, up to the moment when it shall reach its goal.”

“What?” shouted the general and the major in great surprise.

“Undoubtedly,” replied Barbicane composedly, “or our experiment would produce no result.”

“But then,” replied the major, “you will have to give this projectile enormous dimensions.”

“No! Be so good as to listen. You know that optical instruments have acquired great perfection; with certain instruments we have succeeded in obtaining enlargements of 6,000 times and reducing the Moon to within forty miles’ distance. Now, at this distance, any objects sixty feet square would be perfectly visible.

“If, then, the penetrative power of telescopes has not been further increased, it is because that power detracts from their light; and the Moon, which is but a reflecting mirror, does not give back sufficient light to enable us to perceive objects of lesser magnitude.”

“Well, then, what do you propose to do?” asked the general.

“Would you give your projectile a diameter of sixty feet?”

“Not so.”

“Do you intend, then, to increase the luminous power of the Moon?”

“Exactly so. If I can succeed in diminishing the density of the atmosphere through which the Moon’s light has to travel, I shall have rendered her light more intense. To effect that object it will be enough to establish a telescope on some elevated mountain. That is what we will do.”

BARBICANE HOLDS FORTH.

“I give it up,” answered the major. “You have such a way of simplifying things. And what enlargement do you expect to obtain in this way?”

“One of 48,000 times, which should bring the Moon within an apparent distance of five miles; and, in order to be visible, objects need not have a diameter of more than nine feet.”

“So, then,” cried J.T. Maston, “our projectile need not be more than nine feet in diameter.”

“Let me observe, however,” interrupted Major Elphinstone, “this will involve a weight such as—”

“My dear major,” replied Barbicane, “before discussing its weight permit me to enumerate some of the marvels which our ancestors have achieved in this respect. I don’t mean to pretend that the science of gunnery has not advanced, but it is as well to bear in mind that during the middle ages they obtained results more surprising, I will venture to say, than ours. For instance, during the siege of Constantinople by Mohammed II., in 1453, stone shot of 1,900 pounds weight were employed. At Malta, in the time of the knights, there was a gun of the fortress of St. Elmo which threw a projectile weighing 2,500 pounds. And, now, what is the extent of what we have seen ourselves? Armstrong guns discharging shot of 500 pounds, and the Rodman guns projectiles of half a ton! It seems, then, that if projectiles have gained in range, they have lost far more in weight. Now, if we turn our efforts in that direction, we ought to arrive, with the progress on science, at ten times the weight of the shot of Mohammed II and the Knights of Malta.”

“Clearly,” replied the major; “but what metal do you calculate upon employing?”

“Simply cast-iron,” said General Morgan.

“But,” interrupted the major, “since the weight of a shot is proportionate to its volume, an iron ball of nine feet in diameter would be of tremendous weight.”

“Yes, if it were solid, not if it were hollow.”

“Hollow? Then it would be a shell?”

“Yes, a shell,” replied Barbicane; “decidedly it must be. A solid shot of 108 inches would weigh more than 200,000 pounds, a weight evidently far too great. Still, as we must reserve a certain stability for our projectile, I propose to give it a weight of 20,000 pounds.”

“What, then, will be the thickness of the sides?” asked the major.

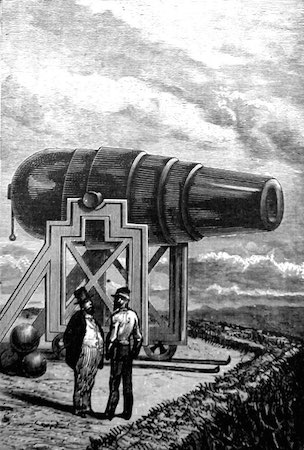

THE RODMAN COLUMBIAD

“If we follow the usual proportion,” replied Morgan, “a diameter of 108 inches would require sides of two feet thickness, or less.”

“That would be too much,” replied Barbicane; “for you will observe that the question is not that of a shot intended to pierce an iron plate; it will suffice to give it sides strong enough to resist the pressure of the gas. The problem, therefore, is this—What thickness ought a cast-iron shell to have in order not to weight more than 20,000 pounds? Our clever secretary will soon enlighten us upon this point.”

“Nothing easier,” replied the worthy secretary of the committee; and, rapidly tracing a few algebraical formulae upon paper, among which n2 and x2 frequently appeared, he presently said:

“The sides will require a thickness of less than two inches.”

“Will that be enough?” asked the major doubtfully.

“Clearly not!” replied the president.

“What is to be done, then?” said Elphinstone, with a puzzled air.

“Employ another metal instead of iron.”

“Copper?” said Morgan.

“No; that would be too heavy. I have better than that to offer.”

“What then?” asked the major.

“Aluminium!” replied Barbicane.

“Aluminium?” cried his three colleagues in chorus.

“Unquestionably, my friends. This valuable metal possesses the whiteness of silver, the indestructibility of gold, the tenacity of iron, the fusibility of copper, the lightness of glass. It is easily wrought, is very widely distributed, forming the base of most of the rocks, is three times lighter than iron, and seems to have been created for the express purpose of furnishing us with the material for our projectile.”

“But, my dear president,” said the major, “is not the cost price of aluminium extremely high?”

“It was so at its first discovery, but it has fallen now to nine dollars a pound!”

“But still, nine dollars a pound!” replied the major, who was not willing readily to give in; “even that is an enormous price.”

“Undoubtedly, my dear major; but not beyond our reach.”

“What will the projectile weigh then?” asked Morgan.

“Here is the result of my calculations,” replied Barbicane. “A shot of 108 inches in diameter, and 12 inches in thickness, would weigh, in cast-iron, 67,440 pounds; cast in aluminium, its weight will be reduced to 19,250 pounds.”

“Capital!” cried the major; “but do you know that, at nine dollars a pound, this projectile will cost—”

“One hundred and seventy-three thousand and fifty dollars ($173,050). I know it quite well. But fear not, my friends; the money will not be wanting for our enterprise. I will answer for it. Now what say you to aluminium, gentlemen?”

“Adopted!” replied the three members of the committee.

So ended the first meeting. The question of the projectile was definitely settled.