Amsterdam

September, 1633

Louis Elzevir noticed a shadow over his shoulder as he finished the last bit of goldwork on the exquisite, red-leather bound tome he had been laboring over for weeks. The twenty-nine-year-old journeyman had slaved over this volume; everything from the typesetting, to the printing of each page, to the bookbinding was by his own hand. Louis poured his soul into this order. It was designed to show the printers of Amsterdam that he was worthy to join their ranks. Louis wished to get married, set up his own shop, and start a family. He would need this book and many more like it to show that he was ready. Slowly, not sure who was casting the shadow, Louis turned around. The master of the shop, Willem Jansz Blaeui, was looking over Louis' shoulder at the newly finished book. Louis stepped aside as the book was picked up for inspection. The master turned the pages carefully examining the printing on the pages, several of the illustrations, and even tested the quality of the binding by opening the book well past flat. Blaeu's face was as inscrutable as a sphinx until he slowly and carefully set down the book and broke into a smile. "A fine work worthy of presentation to a distinguished customer, Louis. If your work continues like this, I will be happy to support your elevation to master when the time comes."

Louis practically strutted out of the shop that day. Blaeu was old and would need someone to take over the shop within the next few years. If Louis could take over Blaeu's business or even just a few of the more valuable contracts, like the one with the Athenaeum, his future was assured. He had come to Amsterdam only a few months before, lured by rumors of booming business and room for more masters. It was now all so close to his grasp. Louis caught the eye of a few of his fellow journeymen, and together they went to one of their favorite taverns to celebrate.

The next morning, Louis' head ached. Too much strong beer had passed between his lips the night before and now he had to drag himself into work. Louis struggled to get ready for the day, and then staggered out of his lodgings to visit his favorite cook shop for some breakfast to help soothe his hangover. The sun was shining far too brightly for Louis' liking and despite how pretty the day was starting out, everything seemed to pall. There were far fewer people on the streets than there should have been at this hour, and those that were on the streets were huddled in small groups. The past few days had been like this. Everyone was waiting on news of the Dutch fleet that had sailed out to meet the Spanish blockade. The Dutch fleet was unstoppable and was supported by the strong French and English fleets, but lately the world had been turned upside down by the odd new town in the Germanies. Nothing seemed to be certain anymore, including the strength of armies. An unstoppable Spanish army had been burnt to a crisp in the Wartburg, and the mighty Catholic army had suffered several defeats, including the loss of both Tilly and Wallenstein. Nothing seemed certain anymore.

Louis quickened his pace and swiftly reached the cook shop. Several of his friends were there already, looking much as Louis felt. The shop owner took one look at their table, ducked behind the counter, and pulled out an odd bluish-white box.

"Here, these are better than any other remedy I know for curing the effects of too much ale. They come from an up-time recipe using essence of willow bark and I guarantee they actually work," the shop owner wheedled.

He then opened the box and let Louis and his friends examine the contents of the box, some odd blue pellets. After some quick dickering over price, Louis bought two of the pills and his usual breakfast order.

Louis was only halfway through his meal when an acquaintance, Karel, burst into the shop carrying some barely dry broadsheets. Karel was trembling and his face was pallid.

"Karel, what's wrong? Here, come sit by me and calm down," Louis said and patted the bench beside him.

"Calm down?! The Dutch fleet has been destroyed!! Haarlem has fallen! The Spanish are at the doorsteps of The Hague and we are next! How can I be calm?! Get out of Amsterdam if you can!" Karel shrieked, throwing down the broadsheets on a table. Then Karel paused, as if struck by a horrible thought, and whimpered "Mother!" before rushing out the door.

Louis sat there frozen while one of his friends went and grabbed one of the broadsheets. It only took a quick glance at the broadsheet to confirm what Karel had said. Louis leapt up from the table, ran out the door, and beat a swift path back to his lodgings, sinking onto his bed once he entered his room. What should I do? I can go to work, but if the Spanish were coming, what is the point? The Spanish burned towns and people wholesale. They'd put everyone to the sword in Amsterdam. It would be worse than Magdeburg if I stay here, death by either starvation and disease or by a sword. I have no family in Amsterdam, no reason to stay, other than my dreams of opening a shop here. At the thought of family, Louis sprang up and started gathering up his meager possessions and cramming them into a rucksack. He would be a true journeyman once more and see what Amsterdam's fate would be.

****

Leiden

May, 1634

For almost nine months, Louis had lingered in Leiden, waiting for an opportunity to return to Amsterdam. Fortunately, his uncle and cousin had room for a journeyman in their shop, and it was interesting, for the first few months at least, to study the extensive collection of type his family owned, which covered everything from common typefaces for Latin and Greek, to exotic and rare ones like Syrian and Ethiopianii. When he wasn't assisting his cousin Abraham with the presses, he was helping his Uncle Bonaventure in the bookshop, binding the books to get them ready for sale. It was worthwhile work that increased his already extensive skill set, but there was no room for another master in Leiden. There was not enough demand for another person to set up a shop, and all of the master printers were in fairly good health or had a different successor in mind. Based on the newspapers and the occasional letter he received from friends stuck in the city, Louis thought the siege was a truly unusual one. There was no disease in either the city or the Spanish camp, goods and money were flowing into and out of the city, and the Prince of Orange was negotiating a settlement with the Spanish prince in charge of the siege. Louis was merely waiting for word that it was safe to return.

For almost nine months, Louis had lingered in Leiden, waiting for an opportunity to return to Amsterdam. Fortunately, his uncle and cousin had room for a journeyman in their shop, and it was interesting, for the first few months at least, to study the extensive collection of type his family owned, which covered everything from common typefaces for Latin and Greek, to exotic and rare ones like Syrian and Ethiopianii. When he wasn't assisting his cousin Abraham with the presses, he was helping his Uncle Bonaventure in the bookshop, binding the books to get them ready for sale. It was worthwhile work that increased his already extensive skill set, but there was no room for another master in Leiden. There was not enough demand for another person to set up a shop, and all of the master printers were in fairly good health or had a different successor in mind. Based on the newspapers and the occasional letter he received from friends stuck in the city, Louis thought the siege was a truly unusual one. There was no disease in either the city or the Spanish camp, goods and money were flowing into and out of the city, and the Prince of Orange was negotiating a settlement with the Spanish prince in charge of the siege. Louis was merely waiting for word that it was safe to return.

Louis had spent a long, hard day in the important job of beater, inking the type before it was pressed. It was a task that showed off his skills as a printer, but it felt pointless to show off when there was no room for further advancement and his kinsmen did not seem to notice when Louis produced exquisite pressings over and over, did some excellent work binding every page neat and straight, or other little things which showed off his skill, while the other journeymen seemed to show half his skill and be showered with praise. However, if the ink was fat when he was the beater, a page or two crooked either in a pressing or after binding, or he got caught playing quadratsiii, he received a harsher punishment and lecture than anyone else even if they were playing quadrats with him. He was family and was expected to be the best and set a good example. Louis couldn't wait to leave Leiden and return to Amsterdam where he would be seen as another senior journeyman, instead of "family" and held to an equal level with his peers instead of a ridiculously high standard no mortal could meet.

Finally, the long day was over. Louis and several of the other journeymen washed up and headed to their favorite tavern to grab some dinner. As soon as he entered, the publican waved him over to the bar and held out a letter. It had one of those new portraits on it to show the postage had been paid, this one in the colors of the House of Orange. It was from Karel, who had been unable to flee Amsterdam with his infirm mother and younger siblings, so he had endured the siege instead.

Full of anticipation, Louis tore open the wax seal and started reading Karel's slightly messy scrawl. The letter began promisingly; Karel was now the master of his own shop. The printers and booksellers who had stayed behind had decided to confiscate the shops of those who had fled and sold them at market price to the available journeymen. Lucky Karel, Louis thought jealously. Then there came the crushing blow, Karel wrote, "Although you are a great printer and bookmaker worthy of a shop anywhere and I would support your elevation here in Amsterdam, the rest of the guild is not ready to admit any journeyman who fled to the rank of master. I do not know if this will change eventually. You should be able to return now if you wish, but there is not a place here for you. I have heard that Grantville and Magdeburg have plenty of opportunities for journeymen to become masters. Maybe you should try there instead. They will welcome a printer and bookmaker of your skill."

Louis barely glanced at the rest of the letter. Karel prattled on about an up-time doctress treating his mother, the wonders of the Committee of Correspondence sanitation procedures, and other inanities. Louis' appetite was gone. A black depression was engulfing him. Amsterdam has no place for me anymore? That blasted whoreson! I fled when you warned me in such dire terms of the looming siege. Now you're a master and have the temerity to tell me that because I fled the siege, I am not welcome in Amsterdam? The only reason you didn't flee was because your mother couldn't travel fast enough to beat the Spanish army, otherwise you would have run from Amsterdam faster than I had. Curse you, Karel! Louis slumped onto a bench and tried to cure his woes with food, ale, and some ginever.

****

Leiden

June, 1634

Louis functioned in a fog. His dreams were dead. His work suffered from the black cloud surrounding him. Pages were crooked and smeared, bindings were poor, and Louis barely spoke and never smiled. Even his kinsmen seemed to be worried about him, barely chastising the sudden drop in the quality of his work and insisting Louis eat his breakfast and dinner with family instead of on his own. At each meal, he was subjected to an interrogation to find out what was wrong.

Sunday dinner at Abraham's residence had been the worst. The entire meal was uncomfortable, with Abraham asking prodding questions like "Louis, what is wrong with you? Your work is terrible of late and you attitude is detrimental to everyone around you. Do you want to be dismissed?"

Abraham's wife Marie made things even more painful by trying to coddle him with comments like "Now dear, don't push Louis. I'm sure Louis will tell us if anything is wrong when he is ready. He knows he can trust us, and we will do anything in our power to help him." Worst of all, Abraham's family was there including his eleven-year-old cousin Jean, drinking in the whole awkward scene.

Finally, Louis blew up at them. "Someone I once called a friend just wrote to me that I'm no longer welcome in Amsterdam because I'm a coward and should try my luck in Magdeburg or Grantville! No one wants me in Amsterdam, there's no future for me in Leiden, and I doubt there is much of a market for scholarly books in either Grantville or Magdeburg!" Louis pushed himself back from the table, stormed out of the dining room, slammed the door behind him. He stomped back to his meager lodgings. He and Abraham had barely spoken even when Louis worked in the print shop, but he was sure that Abraham had informed Bonaventure about Louis' words and behavior and that the pair were planning to dismiss him.

Louis was working for Bonaventure binding books. He tended to make fewer mistakes at this particular art. The day was bright and sunny, which felt like it was mocking him. He had been hard at work for a few hours when Bonaventure had strolled into the small, brightly-lit building in his typical cheerful mood. Then Abraham had stormed into the shop bellowing about dirty thieves and worthless kinsmen, before Bonaventure had steered him into the office to calm him down. Louis expected that he was in for a tongue-lashing at the least and would probably be dismissed from the shop. He probably deserved it. I'm useless. Everyone knows I cowardly fled, and no one wants me in Amsterdam. Karel suggested I go to Grantville or Magdeburg, but neither has a university, and I doubt there is room for a bookseller and printer with a scholarly bent. My kinsmen are surely going to dismiss me, and I have no idea of where to go to next, Louis thought dejectedly.

After what had seemed to be an eternity, his uncle and cousin staggered from the office in a better mood, but it was unclear if that was due to a productive discussion, or the relief one usually felt after making a difficult decision. Louis felt his stomach fall to the floor when his cousin looked at him, extended an accusatory finger and said, "Louis, we have business to discuss." Feeling the heat of the stares of everyone else in the shop on his back, Louis slumped into the office, struggling to look nonchalant about the expected dismissal.

As soon as he entered the office, Louis took note of the drained ginever bottles on the desk. It wasn't normal for his kinsmen to resort to liquid courage. That was usually for mourning or celebration. To his surprise, Uncle Bonaventure gestured for him to sit down, instead of keeping him standing for a dressing-down. Feeling a touch apprehensive, Louis sat down in one of the comfortable chairs that were usually reserved for clientele and looked across the room at his uncle and cousin. Everything felt off, and Louis did not trust the smiles on the faces of his uncle and cousin.

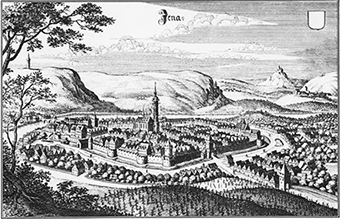

His uncle took a breath, seemingly to gather his thoughts, and began. "Louis, we know that you are upset about Amsterdam and have been trying to decide what to do next, and we have a little proposal for you. We think it would be smart for you to go to Jena to study up-time printing and publishing methods. At the Frankfurt fair, the customers only wanted up-time books. Those printers using new methods from Grantville had more copies of many different books than we could produce in five years to sell and were doing a brisk trade. We know you would like to be near a university. The one in Jena has a great reputation, and the printers there have been acquiring those new methods. With these skills, you should be able to set up a shop wherever you like."

Louis breathed out deeply as he digested his uncle's words. To give up on my dream of Amsterdam will make it official I am a failure, or will I be a failure if I just cling to my dashed dream and give up on my future? Abraham cleared his throat, looked at him and said, "If you do choose to go to Jena, there is a favor I would like to ask of you. I would like you to escort Jean to Jena to begin his apprenticeship at one of the printing or publishing houses there to learn both traditional and up-time printing methods. While you are in Jena I would appreciate it if you kept an eye on Jean and ensured that his apprenticeship and education are suitable for when he takes his place here."

Louis fought the urge to sigh. The request was one he should have expected. As a senior journeyman of almost thirty and family, Louis was the perfect person for the job of escorting Jean to find an apprenticeship. Jean was family, and Louis loved him as a kinsman, but Jean was trying at the best of times. The boy was smart, but he was already gaining a reputation for being enthusiastic, yet inconsistent. Little things like starting to sweep a floor to impress people and then getting distracted partway through, building a grand model ship to impress his uncle, Isaac, and stopping midway through, and heaps of other partially complete tasks and chores. Jean tended to dream big but then would not put in the work to make his dreams bear fruit. It was a tendency that he would hopefully grow out of or get beaten out of him by the right master. Louis could also guess that when Uncle Bonaventure's eldest son Daniel was ready, Louis would be asked to find an apprenticeship for him, too. But as much as he didn't like it, it appeared the best way forward would be to forget Amsterdam and forge a new path. So off to Jena he would go. At least it had a nice proper university so he could print for the scholarly Latin trade, although he wasn't sure if there would be room for him to become a master.

After ten days of preparation, Louis and Jean set off for Jena, bearing letters of introduction to the master printers there. Uncle Bonaventure also included a letter to Dr. Green and the Bibelgesellschaft in order to start a dialogue with a potential new client, since they had been so kind to write him about the wonderful Bibles that sadly didn't sell well.

****

Near Arnheim

July, 1634

Five days, only five days on the road, and Jean would not stop whining about how his feet were aching. True, Jean had never traveled so far in his life, but Louis was on his last nerve. Even being kind to Jean and carrying both of their rucksacks for a while didn't alleviate the complaints. Then as they came around a bend in the road, he spied a welcome sight, a slightly ramshackle inn where they could stop for a greatly needed midday meal. Sitting down and eating would hopefully stall Jean's complaints for a little while. The boy really needed to develop some stamina, endurance, and forbearance in Louis' opinion. Once he was apprenticed, Jean would have all of the worst jobs in the shop. Constant complaining would win him no friends. It was best if he were broken of the habit as soon as possible. But now it was time to get some food. They could venture on, but it would likely be another hour at least before there was another coaching inn, and Louis' stomach was rumbling. Louis started to enter the coaching inn, took one look at the dim, dank interior of the inn and instead steered Jean to a table beneath a large oak tree. Then Louis ventured inside the inn to order two steins of small beer and food for two. First came the two small beers, some bowls of stew with a bit of crusty bread, then there was a platter of stinky, runny cheese and sausage. Louis gave Jean a stern look and said, as gravely as he could, "Jean, eat the stew and bread. Don't eat the cheese and sausage."

Jean rolled his eyes at Louis and had the nerve to say, "But Louis, they both look tasty. I love cheese." Then Jean grabbed a few pieces before Louis could push the platter out of Jean's reach, and swiftly plopped them in his mouth. "Mmm, this is really good. Louis you should try some." Louis just fought the urge to sigh and pushed the platter away so Jean couldn't grab more. Hopefully, Jean wouldn't learn why Louis had avoided the platter.

Sadly, not long after they reached another coaching inn to stop for the night, Jean learned why Louis had told him not to eat the platter of cheese and sausage. They had barely entered the inn and sat down to supper when Jean broke out in sweat and his face blanched. Instead of a nice supper followed by chatting with their fellow travelers to pick up the latest news and gossip, Jean spent the evening in their room groaning over a chamber pot. The next morning, Jean was still pale and ate only bread with a bit of broth. They made very slow progress for the next two days until Jean recovered from his self-inflicted illness. After that, Jean only ate what Louis indicated was okay.

****

Jena

July, 1634

Finally, the pair reached Jena. Jean had learned to stop complaining around ten days into their journey, thank goodness, but that didn't stop Jean's constant questions about everything. Louis found lodgings at an inn that wasn't too expensive but looked reasonably clean. Then he and Jean rifled through their packs to find a precious parcel. Within were letters sealed with wax. "Louis, what are those? Why do we need them now?" Jean asked.

Finally, the pair reached Jena. Jean had learned to stop complaining around ten days into their journey, thank goodness, but that didn't stop Jean's constant questions about everything. Louis found lodgings at an inn that wasn't too expensive but looked reasonably clean. Then he and Jean rifled through their packs to find a precious parcel. Within were letters sealed with wax. "Louis, what are those? Why do we need them now?" Jean asked.

Louis patiently answered, "Jean, these are letters of introduction your father and Uncle Bonaventure wrote for us. It will be hard to find a master willing to take you without a proper letter of introduction. I need them as well to help prove my status and skills. The masters of Jena will want to know who we are and where we come from. Let's grab a quick meal and then go meet the printers here. I think Uncle Bonaventure recommended we visit Ernst Steinmanniv first." So, after some lunch to recover from their travels, they set out towards Steinmann's shop.

Ernst Steinmann had a large print shop from his father. It was located right near several of the University of Jena's important buildings, as befitted a notable shop. The shop reminded Louis of the shop founded by his grandfather in Leiden. With some trepidation, Louis entered with Jean trailing behind. The Elzevir name wasn't a bad one in printing and bookselling, and hopefully, Steinmann wouldn't mind taking on the Elzevir boys in exchange for apprenticeships and journeymen berths for his own kin with the Elzevirs in Leiden. The familiar scents of paper and ink filled the air. It was noisy and bustling. There were only the slightest of glances at the two strangers in the shop. Everyone seemed to be very intent on the task at hand or at the drama occurring at the far end of the shop near some boxes of type. A well-dressed, dark-haired man who looked only a few years older than Louis was loudly rebuking a sandy-haired man Louis' age while waving around a printed page and gesturing at several more. Finding a man slightly older than him who appeared to be supervising, or simply watching the work going on all around him, Louis asked where Meister Steinmann could be found. A finger pointed at the well-dressed man.

Louis hesitated, debating what to do. Jean looked slightly scared and anxiously tugged on his cousin's sleeve. It would have been better to wait until Steinmann was in a better mood, but there was only so much money in the purse Abraham and Bonaventure had given them for the journey. They needed to find a willing master or masters quickly. Taking a quick breath to brace himself and bringing his courage to bear, Louis and Jean approached the man identified as Steinmann. As they approached, they heard, "Just because up-timers will accept a blurry, crooked page does not excuse printing one. The scholars of Jena and Europe demand better, and so do I. If you want to continue printing sloppily and rushed, you are dismissed from this shop." Steinmann whirled around to face Louis and Jean as soon as he noticed them. "Who are you and what do you want?" Steinmann barked.

Louis bowed slightly and then held out the letters from Uncle Bonaventure and Abraham. "How do you do, Meister Steinmann, I presume? My name is Louis Elzevir, and this is my cousin Jean Elzevir. We are seeking a master printer to work under. I am a senior journeyman, and my cousin is seeking to begin an apprenticeship. The Meister Elzevir speak highly of your skill and knowledge." Louis barely kept a nervous tremor out of his voice and thankfully, his hands were not shaking. Jean, however, was trembling like a leaf.

Ernst Steinmann inspected Louis and Jean, with the glare softening. "I see Bonaventure has not lost his good taste. I run a select shop and work heavily with the scholars of the University of Jena. I am looking for a new journeyman at the moment, and I am always open to taking on an apprentice." Steinmann glared at the sandy-haired youth, who turned beet-red. "Let's discuss this more in my office, shall we?" Steinmann motioned for the pair to follow him to a door on the furthest wall.

Once inside, Louis glanced at their surroundings. In the office, there was a small desk that was well-organized with one tidy stack of papers and another of books. On the walls on either side of the desk were bookshelves lined with volumes, the cloth of the binding and the gilding still bright. Behind the desk, there were two small windows covered with oilcloth. In one corner opposite the desk, there were several well-constructed wooden chairs. In the other, there was a small stack of ornate cushions. After Steinmann closed the door behind them and gestured for the pair to bring over and take a seat on the chairs, Jean started to move towards the cushions, but Louis stopped him. Those cushions would only be added to the chairs for the comfort of important clientele, not for the likes of Louis and Jean. It was a kind gesture that they were allowed to sit in the first place, instead of stand.

Once Louis and Jean were seated, Steinmann began peppering Louis with questions designed to confirm his skill level and technical knowledge. Once Steinmann was certain what the pair already knew of the arts of printing and bookmaking, the important question was asked, "What is it you are looking to learn? I have a host of skills and techniques I am willing to teach each of you, but I find it useful to start with what you are interested in learning."

Taking a moment to gather his thoughts and quickly nudge Jean to warn him to keep quiet when he started to open his mouth, Louis began, "We are looking for a few things. One is to learn or expand our knowledge of traditional techniques. The other is to learn up-time techniques." Louis didn't bother mentioning becoming the master of his own shop. Steinmann was only a little older than Louis and had only a few years before inherited it from his father. This was not a shop Louis could take over.

Steinmann snorted at the mention of up-time techniques. "Do you want to be like my journeyman who just ruined a folio of paper? The current methods coming out of Grantville are slovenly and slothful. The only benefit is speed, while the results are smeared and crooked. I pride myself on the quality of my publishing. I will not accept anything that messy. Many of the books that came from up-time are splendidly printed, but the new techniques are wretched. If you wish to understand what I mean, go visit Barbara Weidnerv, Johann's widow, and her second husband Christoph Kuche. I will be glad to train you both if you put aside this foolishness."

After a few more minutes of idle chatter, both Louis and Jean thanked Meister Steinmann for his time, requested a few days to mull the decision over, and headed back out onto the streets of Jena. Steinmann would not be suitable if they wished to learn up-time printing techniques, and his family's instructions were to find someone or someones to train Jean in the new methods. Steinmann's offer was also of little use to Louis. Louis was looking to become a master, and there would be no room for advancement in Steinmann's shop.

So Louis decided to visit the shop Steinmann had mentioned, that of Barbara Weidner and her second husband, Christoph Kuche. Although Christoph Kuche was the master of the shop, it was owned by Barbara Weidner, who would have been a master printer if she were a man. The shop was a fairly small one and situated not as close to the university itself. However, it appeared to be quite well-built and well-maintained. After entering the building, Louis was surprised by how quiet and still it was. Most print shops were filled with the sound of the presses in operation and the small clinks as the type were set in a page. Instead, there was an odd rat-a-tat-tat sound coupled with a chime, plus odd rubbing sounds. No one was standing near the press, and all attention was on a contraption with what appeared to be cylinders on it and some trays. One person was feeding in paper and watching the trays while another cranked the handle on the large machine. At another station was a small device with a sheet of paper jutting out of it that was unlike anything Louis had ever seen. It had large coins on sticks that someone was pressing down and was the source of the odd rat-a-tat-tat and chime. A third station had someone with a razor blade carefully cutting out letters. The final station had someone coating pages with wax. Hovering over it all was a respectably dressed medium-sized woman with gray hair streaked with chestnut. "Is this a printer's shop or have we come to the wrong place?" Louis wondered aloud. Jean looked dumbfounded next to him.

The woman turned around when she heard Louis speak. "This is indeed a print shop, a very modern one. Are you looking to publish something? We can produce large runs of pamphlets and broadsheets quickly and at a reasonable rate."

"My name is Louis Elzevir and this is my cousin Jean Elzevir." Louis gestured to his cousin next to him. "We are looking for a master printer to work under. I am a senior journeyman and Jean would like to begin his apprenticeship." Once again, Louis held out the letters of recommendation that Uncle Bonaventure addressed to Meister Christoph Kuche and Barbara Weidner.

Barbara Weidner nodded to the pair and took the letters. She called over to the sallow-faced youth who was working at the cutting station. "Hans, can you go and fetch Meister Kuche? I believe he is at a meeting in the tavern down the street." As Hans went off to fetch the master of the shop, its mistress turned her focus back towards the pair of Elzevirs before her. "Let me show you around the shop. I doubt you have seen anything like it in Leiden."

First, she took them over to the large contraption with rollers and trays. "This is a Vignelli duplicator. From one waxed paper stencil, we can produce 50 copies, and when we make a waxed silk stencil for a really large order, we can produce 500 copies." She held up a piece of paper. Some letters were cut out of the top, while the rest of the page felt like it had been forcefully impressed. The whole page was lightly coated with wax. Then she ran the stencil through the duplicator and held out to Louis the resulting printed page. She then repeated the process, using the same stencil. Again, the resulting printed page was of very low quality, but it was produced far faster than Louis had heard of anyone doing so by a printing press. The shop only had a few people on hand to make stencils and operate the duplicator and typewriter, far fewer than his family needed to operate a press or set type, but was producing far more sheets than his family could produce in a week. Now some of Ernst Steinmann's complaints about up-time printing became as clear as crystal.

Next, he was shown how the stencil was made, but Louis barely paid attention to the explanation. The only piece of information he caught was that the odd small contraption with coins on sticks and paper sticking out of it was apparently called a typewriter, and it was used to create the text of the stencil. Barbara Weidner steered the pair through the other stations, but while Jean was reacting enthusiastically to each novelty, Louis was deep in thought, weighing these new methods. So fast, but Uncle Bonaventure and Abraham would dismiss any journeyman who produced a page of such low quality and severely reprimand an apprentice. None of the people who buy our family's books would want a book printed this wretchedly. Maybe a broadsheet or a pamphlet, but we focus on books, and I want to make and sell books. However, these were up-time methods, and he had been told it was important to learn up-time methods as well as find Jean a place to be trained in both up-time and traditional methods. He was starting to feel a touch of despair. Are all up-time printing methods like this? Just speed and sloppiness?! It might be what he was directed to learn, but it wasn't making Louis happy. Then a thought crossed his mind as he looked at the unused press.

Next, he was shown how the stencil was made, but Louis barely paid attention to the explanation. The only piece of information he caught was that the odd small contraption with coins on sticks and paper sticking out of it was apparently called a typewriter, and it was used to create the text of the stencil. Barbara Weidner steered the pair through the other stations, but while Jean was reacting enthusiastically to each novelty, Louis was deep in thought, weighing these new methods. So fast, but Uncle Bonaventure and Abraham would dismiss any journeyman who produced a page of such low quality and severely reprimand an apprentice. None of the people who buy our family's books would want a book printed this wretchedly. Maybe a broadsheet or a pamphlet, but we focus on books, and I want to make and sell books. However, these were up-time methods, and he had been told it was important to learn up-time methods as well as find Jean a place to be trained in both up-time and traditional methods. He was starting to feel a touch of despair. Are all up-time printing methods like this? Just speed and sloppiness?! It might be what he was directed to learn, but it wasn't making Louis happy. Then a thought crossed his mind as he looked at the unused press.

"Do you still use your printing press, or are you planning to sell it?" Louis asked hopefully. Presses were expensive, and it was always worthwhile to acquire one when you could. His own family had entered the bookselling business without presses, subcontracting to printers to produce the books they sold until his cousin Isaac had used his wife's dowry to buy some presses. Louis had dreamed of owning his own press when he finally set up his own shop, but would subcontract if he had to.

"No. We have no plans to sell the press. We still use it a few times a week to make stencils for larger runs," a deep voice replied behind Louis. Louis swiftly turned around. Christoph Kuche had arrived at last. He was a heavy-set man with strawberry-blonde hair who appeared to be slightly younger than his wife. "I see my wife has been giving you the grand tour. Follow me, and we can discuss matters."

Louis and Jean followed Christoph Kuche into a small office, and Kuche took a seat in one of the two chairs behind a long, low table. Barbara Weidner entered behind them and took a seat at the table next to her husband, giving him a small smile as she did so. Louis and Jean remained standing across the table from them. The table itself was covered in messy piles of documents. Throughout the whole office, there were piles of paper everywhere. There was likely some sort of order to the chaos, but Louis couldn't see it. As Louis looked around Kuche, glanced at the letters his wife handed to him. "So what brings you all the way from Leiden?" Christoph Kuche asked.

"Abraham and Bonaventure Elzevir requested that I escort Abraham's son Jean to Jena to find a place for an apprenticeship and learn up-time printing methods in addition to the traditional ones," Louis said and gestured towards his cousin. Jean visibly brightened at the mention of his name and nodded enthusiastically. "I am a senior journeyman, and I also wish to learn up-time printing methods that I hope to eventually use in my own shop." Louis finished.

Christoph Kuche rubbed his chin thoughtfully while his wife bit her knuckle. Then, after exchanging a quick glance with his wife, Kuche said, "We would be happy to take on Jean as an apprentice, but we do not have the funds for a journeyman at this time. The duplicator and typewriter were rather expensive, but are proving quite profitable. We are doing a brisk business in pamphlets and broadsheets. Maybe in a few months, we could afford another journeyman. However, we rarely use the old-fashioned methods here. Jean would have to go elsewhere to learn those ancient arts if he wished to do so, although I can't imagine why. This is the way of the future. If you forget this nonsense of learning the traditional methods, Jean has a place here."

Then Barbara Weidner chimed in. "Have you met with Blasius Lobensteinvi yet? He uses a mix of the old-fashioned methods and some new ones from Grantville. My son, Johann Christoph,vii could not stop talking about the techniques they have been using in the shop when he came home last weekend. He's a senior journeyman working for Lobenstein. I think you would like him; he is a good boy. He's ready for his own shop and has his heart set on inheriting this one." Louis fought the urge to sigh. Even if Barbara Weidner's shop had room for a journeyman, this was not a shop where he could become a master. Her son had the first claim.

Christoph Kuche nodded and said, "Yes, you two should go see Lobenstein. His methods are likely to be more suitable to your purpose. He has one foot in the past and one in the present. Don't bother with Steinmann, the old stick in the mud. Steinmann simply refuses to move with the times and grows crankier every day as he loses money." This was news to Louis, as Steinmann seemed to be quite busy, but then he remembered the dismissed journeyman. Louis was looking for a place he could settle in and being summarily dismissed would ruin that. The couple then stood up and escorted the pair to the door. As Louis and Jean were about to leave, Barbara Weidner held out a small package, asked them to take it to her son, and gave them directions to the shop.

Fortunately, Abraham and Bonaventure had included a letter of introduction to Blasius Lobenstein and, intrigued, the pair set off towards his shop. This was a bit of a trek because Lobenstein's shop was located near some university buildings on the opposite side of town from Steinmann's and Barbara Weidner's. The building seemed to be quaking as they approached it, something Louis had only seen when Abraham was in the process of printing the pages for a large run of books. The press was clearly in use, a good sign for it indicated a busy shop. As Louis and Jean entered, Louis noticed a young man about his age with chestnut hair like Barbara Weidner's who was peeling something that looked like papier-mâché off of a page of type. The man put the mold on a drying rack and then turned to address the pair of visitors, "Hello, what brings you here?"

Louis then introduced himself with, "I am Louis Elzevir and this is my cousin Jean Elzevir. We are looking for Blasius Lobenstein. We also have a parcel for Johann Christoph Weidner from his mother." Louis showed it to the young man.

The young man blushed. "I see you have already stopped by the shop my mother runs. She loves acting as if I am a boy just beginning my apprenticeship instead of a man ready to become the master of his father's shop." He then grabbed the parcel Louis was holding out.

Louis nodded sympathetically. "My uncle and cousin sometimes treat me similarly. They see a young child instead of a senior journeyman. However, do you know where we can find Meister Lobenstein?"

Then Jean rudely butted in. "Why are you making a papier-mâché mold of a whole page of type? If you are making new type, isn't it best to mold one piece at a time?" Louis shot a glare at Jean, who had been warned repeatedly to keep his mouth shut and let Louis do all the talking. Johann Christoph smiled at Jean indulgently.

"It's a new technique Meister Lobenstein picked up from a recent trip to Grantville. I like it a lot," Johann Christoph gushed. "Mother's techniques are only good for broadsheets and pamphlets. This stereotype printing is good for everything and produces a cleaner page more consistently than handset type. I was making one of the molds—they're called flongs by the up-timers. From that, I can make a stereotype, a solid plate of a page." Johann Christoph showed them a very thin lead sheet that was the page of a book, complete with illustrations. He led them to a stack of papier-mâché molds. "The flongs are lightweight and easily stored and shipped. You do not have to store the type for a page when you think there will be large demand or do a potentially error-laden second run if a book is more popular than expected. We can do large runs of books on demand or make flongs and ship them to other printers, and they can ship them to us. We could publish the same book jointly in Leiden and Jena for both universities. Every student can have the exact same books for their classes instead of waiting in line to read books in the library."

Then Johann Christoph showed them a stack of pages printed from a stereotype plate and let Louis examine one of the pages. It's not as good as the best works of my uncle and cousin and Steinmann, but it is on par with our average books. Most of our customers would be pleased by a book of this quality. It is certainly better than what Barbara Weidner was printing. He then rifled through the stack of pages, making sure they were the same as the page he was looking at. So many pages and all are of equal quality. I could never produce this many acceptable pages from one typeset page. The later pressings inevitably becoming messy as the type shifts in the press with each strike.

"Do you still print in a traditional manner, or just this new way?" Louis asked. "I know Jean will need to learn both sets of techniques." He knew that this method would interest his family but his uncle and cousin would not want to completely abandon the traditional printing methods, given the demands of some of their higher-end clientele for books of the finest quality. The scholars and students of Leiden and the rest of their usual clientele, however, would love the cheaper books. This method also intrigued Louis. There was a fortune to be made printing this way, and it would be a useful technique to know.

"We often do a few presses the traditional way before we make a flong," Johann Christoph quickly answered. "That way we can proofread the page and make sure it is perfect before the flong is made. We also will make a presentation version for the right book. Then we make the flong and then the stereotype plate and print the rest from the stereotype plate. We can print a lot of books that way, as well as pamphlets and broadsheets."

To Louis, this sounded exactly like what he had been looking for. The shop has an interesting technique I actually want to learn and could teach Jean the traditional printing methods and an interesting up-time method. With this method, I and the rest of my family will take the book trade by storm. However, life had made a cynic of him. There has to be a fly in the ointment, he thought. I could not have possibly stumbled into a shop that would teach me what I need to finally be back on the path to becoming a master. This seems too good to be true. He fixed his gaze on the drying pages again, trying to see what flaws or problems there could be.

"Indeed we can," a tenor voice behind the trio admiring the drying pages chimed in. All three quickly whirled around. A blond-haired gentleman with a beard and mustache in the Dutch fashion and clothes that looked quite odd to Louis had snuck up beside them. He smiled at the trio in front of him and said, "I am Blasius Lobenstein. Whose ears are you talking off, Weidner?"

Louis launched into a familiar spiel, "I am Louis Elzevir and this is my cousin Jean Elzevir. I have been sent by my uncle, Bonaventure Elzevir, and my cousin, Jean's father Abraham Elzevir, to find a suitable master to oversee Jean's apprenticeship. I am a journeyman and also looking for a master to work under." Yet again, he held out the letters of introduction from Abraham and Bonaventure.

Meister Lobenstein took a deep breath and scrutinized the pair before him. "Hmm, Elzevir. I have noticed your name and mark on many interesting books and journals in Grantville. I expect your family is interested in up-time printing methods and books to sell, with a focus on those already bearing your mark, correct?" Lobenstein said in a faraway voice.

Louis paused, knowing he had to navigate some difficult waters, and chose his next words carefully. "Yes, we would like to learn up-time printing methods and of course are seeking books that would be of interest to our usual customers to print. We seek what you seek, too, and would be happy to partner with you. There are enough books there for all the printers in Europe." He wasn't sure what stance his uncle and cousin wished to take on the books from the future. From what he heard his cousin shout to his uncle, the family had no legal claim, but it would be good to be perceived as having the first claim on the rights to reprint the new knowledge bearing their mark. He hoped his words were enough to assuage Lobenstein. He did not want to ruin this opportunity.

Lobenstein pursed his lips, clearly weighing Louis' words carefully, and pulled his hands out of the pockets in his odd blue pantaloons and thrust them behind his back and rocked slightly on his heels carefully debating what to do with the pair of Elzevirs before him. Then he glanced at Jean fidgeting next to Louis, and his face softened. "Indeed there are, and the same book can be printed in both Jena and Leiden for the respective universities." Lobenstein then gestured for the pair to follow and headed towards a long table on the other side of the building near a window and a bookcase. Weidner went back to work making a flong.

The table itself was stacked with papers and a few books, as well as quills, a penknife, and several inkwells. The nearby bookcase was filled with more volumes. Around the table were several well-constructed wooden chairs, one of which was well-worn with a prime view of the entire shop. Meister Lobenstein took a seat in that chair and gestured for Louis and Jean to sit opposite. Lobenstein peppered Louis and Jean with questions to ascertain their skill levels and appeared slightly pleased when Louis admitted that he was trained in bookbinding as well as printing. Then they reached the heart of the matter, whether Meister Lobenstein would be able to take them. "I will admit that I am looking for another journeyman and would be open to bringing on an apprentice," Lobenstein said in a slow, even tone. "I have been working on acquiring a shop within the Ring of Fire in Deborah to gain better access to the many up-time books, visiting scholars, and to have the freedom to print whatever I wish without the oversight of the University of Jena. The up-timers do not have any guilds and there is a high demand for more printers. You could build yourself a shop there whenever you want, all you need is the money to do so."

Louis couldn't suppress his expression of surprise at Lobenstein's words. Print whatever you want? Even in Leiden, we were subject to censorship and the usually benevolent oversight of the university. Uncle Bonaventure would think he had died and gone to heaven if we could print anything, no matter how controversial. Usually we had to resort to a fake name or other trick. No guilds, no more hoops to jump through before becoming a master? Louis was sure his work was worthy of a master printer, all that had been delaying him was obtaining residency and building or inheriting a shop. This was bizarre and unheard of. It had to be false.

Acknowledging the surprise on Louis' face, Lobenstein nodded and continued. "I plan on sending Johann Christoph and a few other journeymen to oversee it and I will travel back and forth between the shops. The new shop in Deborah will focus on stereotype printing while I will continue to do a mix of letterpress and stereotype printing here in Jena. I hope to be able to sell not just books but flongs as well. I should be able to maintain a suitable level of training at both locations but if it becomes a problem I plan on simply moving my business there and selling this shop to young Weidner or one of my other senior journeymen, if Weidner insists on waiting to inherit his father's shop."

Louis mused on this. It is possible to take over Lobenstein's shop here in Jena, and there is enough demand that I could build my own shop within the Ring of Fire if I chose to do so? This is what I have been waiting to hear, but what about the scholarly trade? Is it worthwhile to become a master but not run the sort of shop I always expected to? Then Louis asked the question that had been nagging his thoughts, the reason he had chosen to come to Jena instead of going straight to Grantville, "Will you be able to keep the scholarly trade if you move fully to Deborah? The up-timers do not have a university. What happens once all their books have been copied?"

Lobenstein snorted, "I doubt that their library will be exhausted in our lifetime. The number of books there is astounding. True, there is no university, but the akademie they call a high school is viewed by many around here as equal or superior to any university. Scholars flock to it and their library. I am opening a shop in Deborah to be closer to that trade."

Louis barely suppressed a broad smile and nodded at this and asked, "Would you wish for Jean and I to work here in Jena or in Deborah? I would like to work in both Deborah and Jena, but Jean should be trained in both styles of printing here in Jena." Jean, who had been alternating between fidgeting in his chair and staring off into the distance, looked slightly crestfallen and apprehensive. Louis could guess what Jean was thinking. Even in Leiden, stories were being told about the wonders of Grantville. It would be a shame to be so close to them, yet not make the trip. It was likely also slightly troubling to Jean that he might be separated from the comforting presence of Louis, but he would be lucky to have his cousin still relatively close. For Louis, the option of taking over Lobenstein's shop in Jena was a pleasant one, but he wanted to have access to the up-time books within the Ring of Fire, the potential to be free to print anything, and to set up his own shop as soon as he had sufficient funds. His uncle and cousin would also be pleased if Louis could find up-time books in his spare time to copy and send to Leiden. The bonuses he'd receive would ensure he could set up the shop of his dreams very soon.

Lobenstein rocked slightly in his chair as he considered the problem. "Jean should be trained here in Jena, maybe with the occasional trip to Deborah and Grantville." Louis glanced at Jean who was smiling so broadly his head might split in two. Lobenstein then took a deep breath and said, "Louis, it would be best if you spend a month or two here in Jena learning how to do stereotype printing, and then split your time between Jena and Deborah, maybe spending a fortnight or a month in Jena, then another in Deborah. While an additional journeyman printer will be useful here in Jena, your bookbinding skills are needed at both locations." Louis nodded at this feeling quite pleased at the offer, and Jean looked relieved too, safe in the knowledge that he would be seeing Louis frequently.

Louis, struggling to suppress the joy and butterflies in his stomach, said, "Meister Lobenstein, my cousin and I would be honored to work for you." After a little negotiating on Louis' salary and Jean's apprenticeship fee, Louis Elzevir and Blasius Lobenstein shook hands to seal their agreement, and Louis signed the apprenticeship contract for Jean on the behalf of Abraham and his own employment contract. He had succeeded in the task his family had set for him, and he was sure this stereotype printing would be of great benefit to himself and his family. His dream of setting up his own shop was so close he could taste it. Finally, after all of the setbacks he had suffered the previous year after fleeing Amsterdam, his plans for his future were back on course. The future was finally something to look forward to again. Now I just need to earn enough money to set up a shop. How hard could that be?

****

i http://viaf.org/viaf/61587424/

ii https://tinyurl.com/m4op983

iii http://www.environmentalhistory.org/revcomm/features/life-in-a-print-shop/

iv https://thesaurus.cerl.org/record/cnp00526145

v https://archive.thulb.uni-jena.de/ufb/receive/ufb_person_00001013

vi http://www.worldcat.org/identities/lccn-no2005-75671/

vii https://tinyurl.com/kjgpxql