XII

The Woman of Adventure

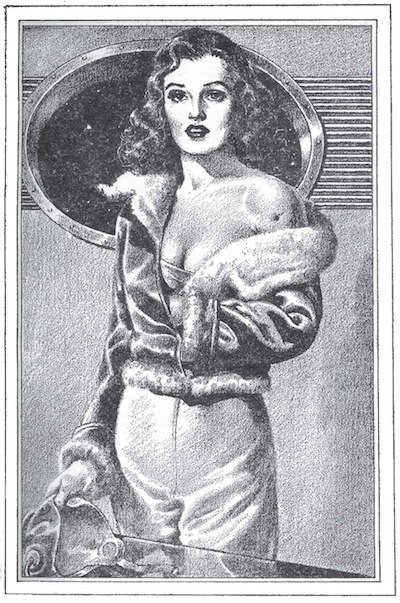

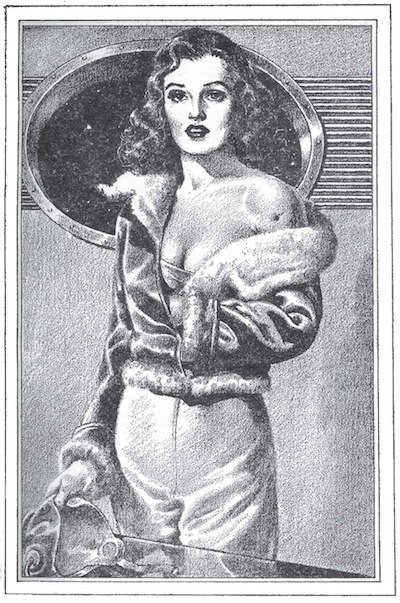

Amoment’s utter silence followed. The woman, with another gesture, drew off the aviator’s cap she had worn; she pulled away the tight-fitting toupee that had been drawn over her head and that had masked her hair under its masculine disguise. With deft fingers she shook out the masses of that hair—fine, dark masses that flowed down over her shoulders in streams of silken glory.

“Now you see me as I am!” said she, her voice low and just a little trembling, but wholly brave. “Now, perhaps, you understand!” “I—but you—” stammered the Master, for the first time in all his life completely at a loss, dazed, staggered. “Now you understand why I couldn’t—wouldn’t—let Dr. Lombardo dress my wound.” “By the power of Allah! What does all this mean?” The Master’s voice had grown hoarse, unsteady. “A woman—here—!”

“Yes, a woman! The woman your expedition needs and must have, if death and sickness happen, as happen they will The woman you would never have allowed to come—the woman who determined to come at all hazards, even death itself. The woman who—”

“But, Lord Almighty! Your papers! Your decorations!”

“Quite genuine,” she answered, smiling at him with dark eyes, unafraid. Through all his dazed astonishment he saw the wonder of those eyes, the perfect oval of that face, the warm, rich tints of her skin even though overspread with the pallor of suffering.

“Madam,” said he, trying to rally, “this is past all words No explanation can make amends for such deception. Still, the secret is yet yours—and mine. Until I decide what to do, it must be respected.”

Past her he walked, to the door, and snapped the catch. She, turning, leaned against the table and smiled. He saw the gleam of perfect teeth. A strange figure she made, with loose hair cascading over her coat, with knickers and puttees, with wounded arm slung in the breast of her jacket.

“Thank you for your consideration,” she smiled. “It is on a par with my conception of your character.”

“Pray spare me your comments,” he replied, coldly. He returned to his desk, but did not sit down there. Against it he leaned, crossed his arms, and with somewhat lowered head studied her. “Your explanation, madam?”

“My papers are en regle,” said she. “My decorations are genuine. Numbers of women went through the great war as men. I am one of them, that is all. Many were never discovered. Those who were, owed it to wounds that brought them under observation. Had I not been wounded, you would never have known. I could have exercised my skill as a nurse, without the fact of my sex becoming apparent.

“That was what I was hoping for and counting on. I wanted to serve this expedition both as a flyer and as a nurse. Fate willed otherwise. A chance bullet intervened. You know the truth. But I feel confident, already, that my secret is safe with you.”

The light on her forehead, still a little ridged and reddened by the pressure of the edge of the mask, showed it broad, high, intelligent. Her eyes were deep and eager with a kind of burning determination. The hand she had rested on the table clenched with the intensity of her appeal:

“Let me stay! Let me serve you all! I ask no more of life than that!”

The Master, knotting together the loose threads of his emotion, came a step nearer.

“Your name, madam!” he demanded.

“I cannot tell you. I am Captain Alfred Alden to you, still. Just that. Nothing more.”

“You continue insubordinate? Do you know, madam, that for this I could order you bound hand and foot, have you laid on the trap in the lower gallery, and command the trap to be sprung?”

His face grew hard, deep-lined, almost savage as he confronted her—the only being who now dared stand against his will. She smiled oddly, as she answered:

“I know all that, perfectly well. And I know the open Atlantic lies a mile or two below us, in the empty night. Nevertheless, you shall not learn my name. All I shall tell you is this—that I am really an aviator. ‘Aviatrix’ I despise. I served as ‘Captain Alden’ for eight months on the Italian front and twenty-one months on the Western. I am an ace. And—”

“Never mind about all that!” the Master interrupted, raising his hand. “You are a woman! You are here under false colors. You gained admission to this Legion by means of false statements—”

“Ah, no, pardon me! Did I ever claim to be a man?”

“The impression you gave was false, and was calculated to be so. This is mere quibbling. A lie can be acted more effectively than spoken. All things considered, your life—”

“Is forfeited, of course. I understand that perfectly well. And that means two things, as direct corollaries. First, that you lose a trained flyer and a woman with Red Cross training; a woman you may sorely need before this expedition is done. Second, you deny a human being who is just as eager as you are for life and the spice of adventure, just as hungry for excitement as you or any man here—you deny me all this, everything, just because a stupid accident of birth made me a woman!”

Her clenched right fist passionately struck the table at her side.

“A man’s world! That’s what this world is called; that’s what it is! And you—of all men—are living down to that idea! You—the Master!”

The man’s face changed color. It grew a little pale, with deepening lines. He passed a hand over his forehead, a hand that for the first time trembled with indecision. His strong teeth gnawed at his lower lip. Never before had he lacked words, but now he found none.

The woman exclaimed, her voice incisive, eager, her eyes burning:

“It is because you are a master of men, and of yourself, that I have taken this chance! It is because I have heard of your absolute sense of justice and fair play, your appreciation of unswerving loyalty and of the heart that dares! Now you understand. I have only one more thing to say.”

“And what is that?”

“If you respect my secret and let me go with you on this great enterprise, no man aboard the Eagle of the Sky will serve you any more loyally than I. No man will venture more, endure more, suffer more— if suffering has to be. I give you my word of honor on that, as a fighter and—a woman!”

“Your word of honor as—”

“A woman! Do you understand?”

Silence again. Their eyes met. The Master’s were first to lower.

“Your life is spared,” he answered. “That is a concession to your sex, madam. Had you been a man, I would inevitably have put you to death. As it is, you shall live. And you shall remain with us—”

“Thank God for that!”

“Till we reach land. There you must leave Nissr.”

“I shall not leave it alive,” the woman declared, her eyes showing dilated pupils of resentment, of anger. “I haven’t come this far to be thrown aside like a bit of worthless gear!”

“You and your machine will be cast off, over the first land we touch,” the Master repeated doggedly. “Whatever information you may give, cannot injure us, and—”

“Stop! Not another word like that, to me!”

Her eyes were blazing now; her right fist quivered in air.

“You accuse me of treason,” she cried. “Oh, what injustice, what—”

“I accuse you of nothing, save of having deceived us all, and of being very much deplacee here. The deception shall continue, as far as the others are concerned. You came to us, as a man. You shall go as one. Your secret shall be absolutely respected, by me. But, madam, understand one thing clearly.”

“What is that?” she demanded, still trembling with indignation.

“The fact that you are a woman has no weight with me, so far as your persuading me to let you remain of the party may be concerned.

Women have never counted in my life. Their wiles, arts, graces, tears, mean nothing to me. Their entreaties seem futile. Their arguments appear like trivial puerilities.

“Other men are sometimes influenced by such. I tell you now, madam, I shall not be. Your entreaties will have no weight. When the time comes for you to leave Nissr, I trust you will go quietly, with no distressing scene.”

A certain grimness showed in the woman’s face, making it sternly heroic as the face of Medea or Zenobia. She answered:

“Do you think me the type that entreats, that sheds tears, that exercises wiles?”

“We won’t discuss your personality, madam! This interview is drawing to an end. Until we reach land, nothing can be done. Nothing, but to look out for your injury. Common humanity demands that your wound be dressed. Is it a serious hurt?”

“Not compared with the hurt you are inflicting, in banishing me from the Flying Legion!”

“Come, madam, refrain from extravagant speeches! What is your wound?”

“A clean shot through the left arm, I think, a little below the shoulder.”

“I realize, of course, that to have Dr. Lombardo dress it would reveal your sex. Could you in any way manage the dressing, yourself?”

“If given antiseptics and bandages, yes.”

“They shall be furnished, also a stateroom.”

“That will excite comment.”

“It may,” the Master answered, “but there is no other way. I will manage everything privately, myself. Then I will let it transpire that there was some injury to the face, as well, and that the mask had to be removed. I can let the impression get about that you refused to allow anyone but me see your mutilated face.

“I can also hint that I have helped you with the dressing, and have ordered you to keep your stateroom for a while. When it comes time to leave Nissr, I will dispatch you as a messenger. Thus your secret will remain intact. Besides, no one will dare inquire into anything. No one ventures to discuss or question any decision of mine.”

Something of hard arrogance sounded in the Master’s voice. The woman thanked him, her eyes penetrant, keenly intelligent, even a trifle mocking. One would have said she was weighing this strange man in the balance of judgment, was finding him of sterling stuff, yet was perhaps cherishing a hope, not untinged with malice, that some day a turn of fate might humble him. The Master seemed to sense a little of this, and took a milder tone.

“I must compliment you on one thing, madam,” said he, with just the wraith of a smile. “Your acting has been perfection itself. And the fortitude with which you have borne the discomfort of that mask for more than a week, to achieve your ends, cannot be too highly praised.”

“Thank you,” she replied. “I would have stood that a year, to be one of your Legion! But now—tell me! Isn’t there any possibility of your reversing your decision?”

“None, madam.”

“Isn’t there anything I can say or do to—”

“Remember, you told me just a minute ago you were not the type of woman who entreats!”