V

In Which the Possibility That Coal Mines Surround the North Pole Is Considered

Are there coal mines at the North Pole? This was the first question suggested to intelligent people. Some asked why should there be coal mines at the North Pole? Others with equal propriety asked why should there not be? It is well known that coal mines are spread all over the world. There are many in different parts of Europe. America also possesses a great many, and it is probable that the United States mines are the richest of all. There are also many in Asia, Africa, and Australia. The more our globe becomes known the more mines are discovered. We will not be in need of coal for at least hundreds of years to come. England alone produces 160,000,000 tons every year, and over the whole world it is estimated 400,000,000 tons are yearly produced. Naturally, this coal output must grow every year in proportion with the constantly increasing industries. Even if electricity takes the place of steam, it will still be necessary to use coal to produce it. The stomach of industry requires coal, it does not eat anything else. Industry is a “carbonivore” and it should be well-nourished.

Coal is used not only as a fuel, but also as a crude substance of which science makes great use. With the transformations to which it has been submitted in the laboratory, it is possible to paint with it, perfume with it, purify, heat, light with it, and even create a diamond with it. It is as useful as iron or even more so. It is fortunate that this last-mentioned metal will never be exhausted, as really the world is composed of it. In reality, the world might be considered a vast mass of iron, as other metals, and even water and stone, stand far behind it in the composition of our sphere. But if we are sure of a continuous supply for our consumption of iron, we are not so of coal.

Far from it. People who are competent to speak, and who look into the future for hundreds of years, always allude to this coal famine. They urge that new coal mines be sought wherever farsighted Nature formed coal in geological times.

“But,” say the opposing party—and in the United States there are many people who like to contradict for the mere sake of argument, and who take pleasure in contradicting—”Why should there be coal around the North Pole?”

“Why?” answered those who took the part of President Barbicane, “because, very probably at the geological formation of the world, the Sun was such that the difference of temperature around the equator and the poles were not appreciable. Then immense forests covered this unknown polar region a long time before mankind appeared, and when our planet was submitted to the incessant action of heat and humidity.”

This theory the journals, magazines, and reviews publish in a thousand different articles either in a joking or serious way. And these large forests, which disappeared with the gigantic changes of the Earth before it had taken its present form, must certainly have changed and transformed under the lapse of time and the action of internal heat and water into coal mines. Therefore nothing seemed more admissible than this theory, and that the North Pole would open a large field to those who were able to mine it. These are facts, undeniable facts. These positive spirits, who do not want to count on simple probabilities, did not question them and were likely to authorize the search for potential coal mines in the Arctic regions.

It was on this subject that Major Donellan and his secretary were talking together one day in the most obscure corner of the “Two Friends” inn.

“Well,” said Dean Toodrink, “is there a possibility that this Barbicane—who will be hanged some day—is right?”

“It is probable,” said Major Donellan, “and I will almost admit that it is certain.”

“Then there will be fortunes made in exploring this region around the pole!

“Assuredly! If North America possesses so many coal mines and, according to the papers, new ones are discovered quite frequently, it is not at all improbable that there are many yet to be discovered. The Arctic territory appears to be an appendix of the American continent. More particularly, it is certain that Greenland belongs to America.”

“Like the head of a horse belongs to the animal,” remarked the major’s secretary.

“I may add that Prof. Nordenskiold, in his explorations of Greenland, has found many sedimentary formations, consisting of sandstones and schists with lignite intercalations which contain a great variety of fossil plants. And in the area of Disko Island, the Dane Stoënstrup recognized seventy-one layers in which vegetable fossils abound, indisputable evidence of the vast amount of vegetation that once flourished around the pole.”

“And higher up?” asked Dean Toodrink.

“Higher up, or rather further up, in a northerly direction,” answered the Major, “the presence of coal is practically established, and it seems as if you would only have to bend down to pick it up. Well, if coal is so plentiful on the surface of these countries, it is right to conclude that its beds must go all through the crust of the globe.”

He was right. Major Donellan knew the geological formations around the North Pole well, and he was not a safe person to dispute this question with. And he might have talked about it at length if other people in the inn had not listened. But he thought it better to keep quiet after asking:

“Are you not surprised at one thing?”

“About what?”

“One would expect to see engineers or at least navigators figure in this matter, while there are only gunners at the head of the North Polar Practical Association?”

It is not surprising that the newspapers of the civilized world soon began to discuss the question of coal discoveries at the North Pole.

“Strata of coal? Where?” asked the Pall Mall Gazette, inspired by the great English merchants who debated the arguments of the N.P.P.A.

“And why not,” asked the editor of the Charleston Daily News, who took the part of President Barbicane, “when it is remembered that Captain Nares, in 1875 and 1876, at the eighty-second degree of latitude, discovered large flower-beds, hazel trees, poplars, beech trees, and conifers?”

“And in 1881 and 1884,” added the New York Witness, a scientific publication, “during the expedition of Lieutenant Greely at Lady Franklin Bay, was not a layer of coal discovered by our explorers a little way from Fort Conger, near Waterhouse? And did not Dr. Pavy say, and not without reason, that these countries are certainly full of coal, perhaps placed there by Nature to some day combat the terrible cold of these sorry regions?”

Against such well-established facts brought out by American discoverers the enemies of President Barbicane did not know what to answer. And the people who asked why should there be coal mines began to surrender to the people who asked why should there be none.

Certainly there were some, and very considerable ones, too. The circumpolar ice-cap conceals precious masses of coal contained in those regions where vegetation was formerly luxuriant. But if they could no longer dispute that there were really coal mines in this Arctic region the enemies of the association tried to get revenge in another way.

“Well,” said Major Donellan during a discussion in the meeting-room of the Gun Club, during which he challenged President Barbicane face to face, “all right. I admit that there are coal mines; I even affirm it, there are coal mines in the region purchased by your company, but go and try to exploit them!”

“That is what we are going to do,” said Impey Barbicane tranquilly. “Go over the eighty-fourth degree, beyond which no explorer as yet has been able to put his foot?”

“We will pass it.”

“Reach even the North Pole?”

“We will reach it.”

And after hearing the President of the Gun Club answer with so much coolness, with so much assurance, to see his opinion so strongly, so perfectly affirmed, even the strongest opponent began to hesitate. They seemed to be in the presence of a man who had lost none of his old-time qualities, quiet, cold, and of an eminently serious mind, exact as a clock, adventurous, but carrying his practical ideas into the rashest enterprises.

Major Donellan had an ardent wish to strangle his adversary. But President Barbicane was solid, morally and physically, having a “large draught”, to employ a metaphor of Napoleon, and, consequently, able to hold against wind and tide. His enemies, his friends and people who envied him knew this only too well.

Ah! This Yankee who had affirmed that he would reach the Pole! Ah! He would put his foot where no human being had yet trod! Ah! He would plant the flag of the United States on the only point of the globe which remains eternally motionless, while the others make their daily movement!

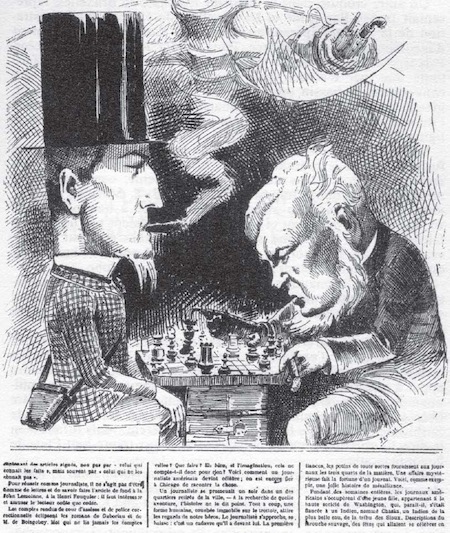

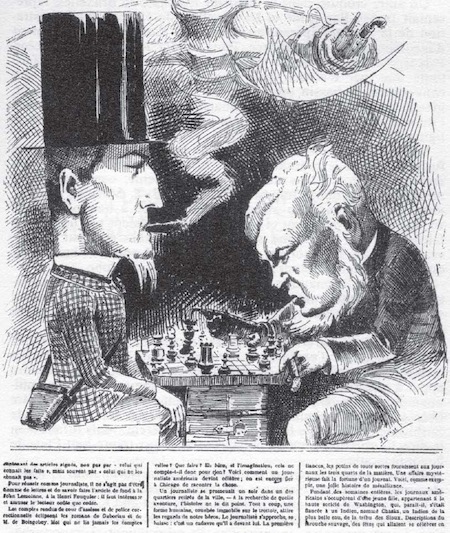

But there were many jealous people, and many jokes and funny stories went round in regard to the members of the Gun Club. Pictures and caricatures were made in Europe and particularly in England, where people could not get over the loss which they suffered in the matter of pounds sterling. Wild caricatures appeared in the different newspapers. In the large show-windows and news-depots, as well in small cities of Europe as in the large cities of America, there appeared drawings and cartoons showing President Barbicane in the funniest of positions trying to reach the North Pole. One audacious American cut had all the members of the Gun Club trying to make an underground tunnel beneath the terrible mass of immovable icebergs, to the eighty-fourth degree of northern latitude, each with an axe in his hand. In another, Impey Barbicane, accompanied by Mr. J.T. Maston and Captain Nicholl, had descended from a balloon on the much-desired point, and after many unsuccessful attempts and at the peril of their lives, had captured a piece of coal weighing about half a pound. This fragment was all they discovered of the anticipated coal-fields. Punch published a cartoon of J. T. Maston, who was as much used for such purposes as his chief. After having tried to find the magnetic attraction of the North Pole, the secretary of the Gun Club became fixed to the ground by his metal hook.

The celebrated calculator was too quick-tempered to find any pleasure in the drawings which referred to his personal conformation. He was exceedingly annoyed by them, and Mrs. Evangelina Scorbitt, it may be easily understood, was not slow to share his indignation.

Another drawing in the Magic Lantern of Brussels represented the members of the Council and the members of the Gun Club tending a large number of fires like so many salamanders. The idea was to melt the large quantities of ice by putting a whole sea of alcohol on them, which would convert the polar basin into a large quantity of punch. And exploiting the word “punch”, did the Belgian artist not increase his irreverence by representing Barbicane as a ridiculous Punchinello?

But of all these caricatures, that which had the largest success was that which was published by the French Charivari, under the signature of its designer, “Stop.” In the stomach of a whale Impey Barbicane and J. T. Maston were seated playing checkers and waiting their arrival at a good point. The new Jonah and his Secretary had got themselves swallowed by an immense whale, and using this new mode of locomotion to pass under the icebergs, that they hoped to gain access to the North Pole.

The phlegmatic President of this new Society did not care much about these pictures, and let them say and write and sing whatever they liked.

Immediately after the concession was made and the Society was absolute master of the northern region, appeal was made for a public subscription of $15,000,000. Shares were issued at $100, to be paid for at once, and the credit of Barbicane & Co. was such that the money ran in as fast as possible. The most of it came from the various States of the Union.

“So much the better,” said the people on the part of the N.P.P.A. “The undertaking will be entirely American.”

So strong, indeed, were the foundations upon which Barbicane & Co. were established that the amount necessary to be subscribed was raised in a very short time, and even thrice the amount. Everybody was interested in the matter, and the most scientific experts did not doubt its success.

The shares were reduced one-third, and on December 16 the capital of the Society was $15,000,000 in cash. This was about three times as much as the amount subscribed to the credit of the Gun Club when it was going to send a projectile from the Earth to the Moon.