CHAPTER VII

THE FIRST DAY OF THE VOYAGE

Just at this moment, 12 o’clock noon, on the day of our departure, Capt. Ewald resisted the ship’s eastward motion due to the earth’s rotation until it was completely overcome, and then the sun ceased his westward flight across the sky and the earth went spinning upon her axis. He then chose the direction of a star with which the moon was at that moment almost in direct line, gauged the ship to this course, and turned on the power. On our craft went day after day through the boundless and dread immensity of space at a speed that must have been equivalent to that of a cannon ball. He held steadily to and bore down upon this course for a period of a little more than twenty-nine days, and in the meantime covered a distance of almost two hundred and forty thousand miles.

After the final start, or our departure proper, even though we were in every way well and thoroughly equipped, I truly regretted that I had ventured to take this trans-ethereal flight, because I thought then that I realized it was not possible for us to get by the dangers that would beset us on every hand. The ship had ne tremors and was running in a somewhat jerky manner. Capt. Ewald and Prof. Purnell were at the running gear trying to adjust properly some of the machinery that did not seem to be working fitly. Prof Rider, who was the only man in the company other than the captain, who could steer the ship, was standing quietly near the center of the sitting room and looking anxiously toward the helm. The rest of the company were seated in the chairs looking wonderingly about at one another. I do not know what others thought nor how they felt; but, as for myself, I entertained the fear that Capt. Ewald and Prof. Rider did not feel themselves masters of the situation. I tried to discern in their actions and in the expressions of their faces a sufficient amount of self-confidence to allay within me the painful emotion of fear excited by the apprehension of impending danger.

Presently the ship righted itself and sped smoothly onward. Everybody appeared greatly relieved, and there opened up at once an all-round conversation. Capt. Ewald left the helm, walked straightway to Prof. Rider, and with a broad and pleasing smile on his face spoke as follows:

“We are now gone; there will be no stopping along the way to let off and to take on passengers; the next landing will be the moon.”

Prof. Rider returned the smile, and in reply said:

“And high she shoots through glorious light,

Above all low delay,

Where nothing earthly bounds her flight,

Nor shadows dim her way.”

Immediately after the ship had been set free from the earth’s rotary motion and the excitement had partially subsided, I prostrated myself upon the floor to peer through one of a number of rectangular panes of glass which had been placed in the floor and arranged so as to form a decagon around a central, upright shaft, to get a view of the earth. I shall never forget the impression this scene made upon me. I saw the earth’s surface plainly–even more so than when we were within her atmosphere; and by the aid of one of the small telescopes I saw distinctly all the beautiful silvery yearns of the great Mississippi system threading their courses through the country and readily discerned the relief in the elevations of every character, and by them easily followed with my eyes the trend of the ranges of hills. I had also a fine survey of most of the Great Lakes and an excellent view of all the large cities within a radius of five hundred miles, including St. Paul, Minn.; Lincoln, Nebr.; Little Rock, Ark.; Birmingham, Ala.; Atlanta, Ga.; Columbia, S. C., and Pittsburgh, Pa.

But it was not the mere fact that I could see the familiar objects enumerated above, at distances so immense, that interested me most; rather, it was the sublimity of the scene that startled me. Although we were moving onward at the almost incredible speed of three hundred and sixty miles an hour, our ship seemed to be standing perfectly still in free space and the earth appeared to be falling from under us as if destined for some great and powerful center of attraction, or even for the uttermost bounds of space; but this was an optical illusion–it was the craft that was moving. I could plainly see the earth, a great, hazy, murky mass, going on her rapid heavy swing upon her axis. The first impression made upon me was that the law of universal gravitation had failed and that as a result the universe was wrecking or going into disorder.

For perhaps fifteen minutes after the final start the ship had been running steadily, when we all slowly and cautiously distributed ourselves around the walls of the sitting room and for the first time gazed with unobstructed view and profound interest through the panes into the infinite realm of God’s dominion. Not a smile played over any one’s lips, scarcely a word was spoken for more than an hour, and I saw clearly depicted in every countenance an expression of the intermingled feelings of fear, awe, and reverence.

The last vestige of my fears occasioned by the perils of the situation departed as I stood gazing into the trackless and shoreless ocean of space at the sublime and awful beauty that from every direction in which I turned my eyes met my anxious gaze. This general view of the heavens was the most appalling and sublime spectacle that I ever beheld or ever expect to behold this side the Judgment Day. No human language as a vehicle for thought is competent even to begin to approach a description of a thing on a scale so stupendous, and the sensation produced by such a panoramic view of the heavens can only be thought of and felt in the soul. (See Fig. 9.)

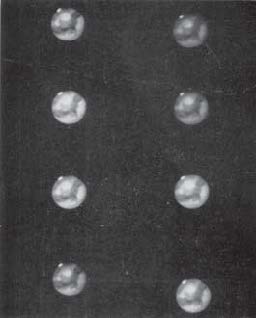

Plate 9. A Panoramic View of the Heavens

This picture gives the reader a faint idea of the view that presented itself to us when we were at a distance of two hundred miles from the earth’s surface and aids him in realizing what the mind can not grasp—the immensity of the universe and the immeasurable distances in trackless space.

If we had a means by which we could travel uniformly a mile a minute, day and night, and were to speed our course in the direction of the remotest planet known to astronomical science, it would require five thousand and fifty-five years to reach the end of the route. Traveling at this same speed it would require forty millions of years to reach the nearest fixed star.

The great concave of the celestial sphere was as black as night. The planets and their satellites, more than five hundred in number, were at once in plain view and appeared much nearer than when viewed from the earth through an atmosphere laden with moisture, dust, and gases, and all of them, even to Deimos and Phobos, the two little satellites of Mars, familiarly known as Dread and Terror, presented well-defined disks and shone with a clear, steady light as they moved on their unknown celestial rhythm of the universe. More than a hundred comets not visible from the earth through a powerful telescope were pretty evenly distributed over the concave of the sky in the vicinity of the sun and moving in every conceivable direction. The fixed stars, which had come out by hundreds of thousands, never before beheld by mortal eyes, appeared to be at, almost infinite distances and shone with a steady, white luster. (See Figs. 6 and 29.)

And the sun, by far the most conspicuous of all objects within our ken of vision, whose great corona had apparently arranged itself into a system of concentric ring’s or bands, was sending off the most luminous cones of rays and pearly streamers of light, with great intensity, for millions of miles, into the dark expanse of the heavens.

At this time Mars, which is almost the size of our own world and which is nearest to the earth of all the superior planets belonging to the major class presented a wonderful aspect. It stood out in bold relief and was, indeed, a “beautiful world on high.” With my unaided eyes I easily traced the shores of its seas and oceans, the bounding lines of the deserts and the verdant regions, and saw very distinctly the south polar “cap” due probably to ice and snow in the planet’s polar regions. By the aid of the great telescope Profs. Monahan and Galvan made a photograph of it. (See Fig. 10.)

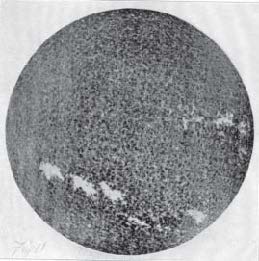

After a partial relaxation of our nervous tension due to the magnificence of the panoramic view of the heavens before us, Prof. Galvan called us to the large telescope to take a view of the sun. This is a wonderful sight. The telescope reveals that the surface of this great luminary has a peculiar mottled appearance not unlike that of an orange skin, and that it is covered also with small, intensely bright bodies irregularly distributed. The light from different parts of the solar disk, one observes, varies in color–that arising from the edges being of a chocolate hue, while that emanating from the center has a decidedly blue tint.

Plate 10. The Planet Mars, 1909

[Yerkes Observatory]

Plate 11. The Sun, Photographed with the Spectroheliograph, 1913

The white blotches are areas of intensely brilliant calcium vapor, which would be invisible on an ordinary photograph.

[Yerkes Observatory]

The sun’s distance from us is ninety-three millions of miles, a magnitude so great that if a railroad could be built from the earth to this great luminary, an express train, traveling day and night without stopping, at the rate of thirty miles an hour, would require three hundred and fifty-two years to reach its destination. Ten generations would be born and would die, and the eleventh generation would see the solar station at the end of the route.

In spite of this tremendous stretch of miles the sun, from our viewpoint, measured more than one-half a degree. This is equivalent to saying that the sun is a globe with a diameter of eight hundred and sixty-five thousand and four hundred miles, an area of two trillion and three hundred and fifty-four billions of square miles, and a volume of three hundred and forty quadrillions of cubic miles. In other words the sun is a globe of such stupendous dimensions that if it were hollow, it would contain one million and three hundred thousand worlds like our own. At first I was startled by such enormous magnitudes, which are far beyond the grasp of human comprehension; but this telescopic view closely followed up with mathematical demonstrations by Prof. Galvan led me to realize beyond the shadow of all doubt that the dimensions which are now attributed to the sun have not been exaggerated.

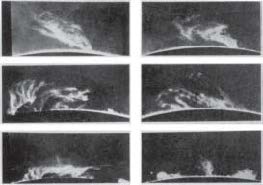

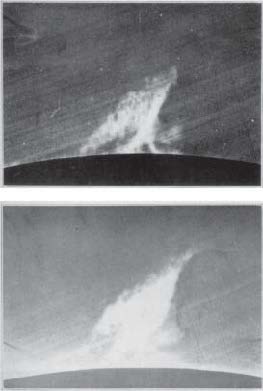

And what is still more wonderful is the fact that the entire surface of this tremendous globular mass, everywhere, is constantly overrun by sweeping floods of hot molten matter. The chromosphere composed largely of luminous, hydrogen gas is the seat of enormous protuberances and projections. Tongues of fire sometimes dart forth at the prodigous speed of one hundred and fifty miles a second to a distance of one hundred thousand miles.

These jets of hot molten matter sometimes make sharp angles with the horizontal plain, and at other times right angles; and, when the jets are vertical, the hot spray dropping back into the seething ocean of fire often takes the form of large trees and reminds the observer of a forest of Sequoia Gigantea. More often the hot descending spray of these great sun-storms, sweeping to the left and to the right, presents the appearance of stupendous prairie fires. (See Figs. 12, 13, 14, 15.)

With the exception of the meteoric bodies, the comets are by far the most numerous of all the heavenly bodies belonging to the solar system and are, without exception, the most fascinating. The suddenness with which they flame out in the sky, the enormous lengths of their trains, the swiftness of their flight, the strange and mysterious forms they assume, their unheralded advent and their departure for the profound depths of interstellar space—all seem to bid defiance to law and to partake of the marvelous. Every person on board the ship finally centered his interest on this particular class of heavenly bodies, and the sensation produced in every instant except in the cases of Capt. Ewald and Profs. Monahan, Galvan, and Rider, was the same—that of dread and loneliness. And Prof. Monahan, as if to excite the superstitious fears of all to a higher pitch, said:

“Comets have been looked upon in every age as—

‘Threatening the world with famine, plague, and war;

To all estates, inevitable losses;

To herdsmen, rot; to plowmen, hapless seasons;

To sailors, storms; to cities, civil treason; and

To us, they may be looked upon as—what?’”

(See Figs. 2, 16, 17.)

Plate 12. A Solar Prominence

This hot Jet extends vertically upward to a distance of eighty thousand miles. The spray falling back into the seething ocean of fire gives the whole the appearance of an isolated tree.

[Yerkes Observatory]

Plate 13. A Solar Prominence Showing Currents in Different Directions.

[Yerkes Observatory]

Plate 14. A Solar Prominence Showing Currents in Different Directions.

More often the hot descending spray of these great sun storms, sweeping to the left and to the right, presents the appearance of stupendous prairie fires

[Yerkes Observatory]

Plate 15. A Solar Prominence Showing Changes.

[Yerkes Observatory]

Plate 16. Giacobini’s Comet. 1908.

[Yerkes Observatory]

Plate 16. Morehouse Comet.

[Yerkes Observatory]

The visible comets farthest away from the sun were mere faint diffused spots of light upon the dark background of the sky, while those near their perihelion distances were very large, exceedingly bright, and accompanied by long fan-like trains. They reminded me of mammoth bombs exploding, and I naturally wondered what hostile hosts of warriors at the outskirts of the universe were bombarding the sun.

At half past twelve o’clock I again directed my gaze toward the earth. Away to the west the more elevated parts of the great system of the Cordilleras were heaving into view, and to the unaided eye the crests of the massive snow-capped ranges appeared as long white lines on the generally darker expanse of the continent.

At one o’clock we were five hundred and thirty miles above the surface of the earth and almost directly over Denver, Colo., which we readily located and recognized. We saw the long range of the Rocky Mountains in high relief go sweeping under us at a speed of nearly a thousand miles an hour, and by the aid of our small telescopes traced the channels of the larger western tributaries of the Mississippi river from their sources to their mouths; and at half past one o’clock we had a grand sweep of the whole Pacific coast from the Gulf of Lower California to the northern boundary of Washington.

This wonderful experience was truly the first and only one that ever brought me to so full a realization of what an immensely large object this old world is. When compared with infinite space she is, in volume, nothing more than a floating particle of dust or even a molecule; but, when viewed from an altitude of seven hundred miles, she is certainly a thing of magnitude. But when seen even from this great distance she does not yet appear as a globe in the sky, but merely as a great convex circle with a constantly expanding circumference. At that time I did not realize that we were very far away from the earth, and comparatively we were not; for on a globe eight inches in diameter our altitude would be represented by only three-fifths of an inch.

Our first lunch in celestial space was served at half past one o’clock. At the close of this meal I was so sleepy that I could scarcely compel myself to stay awake. I was also very much fatigued–as much so as if I had been steadily engaged at manual labor for a whole day on the ten-hour system. My drowsy and weary condition was due partly to the fact that I had been steadily engaged almost the whole of the previous night at getting ready for the long voyage, and in part by the exciting influences of the weird and wondrous beauty to which I had, for the past two hours, been subjected, and which had steadily engaged my willing attention. I then prostrated myself upon one of the couches for sleep and repose.