CHAPTER IV

THE “POPLARS”.

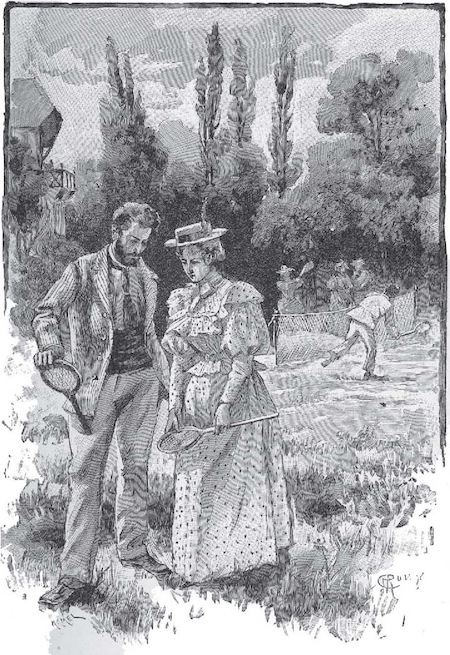

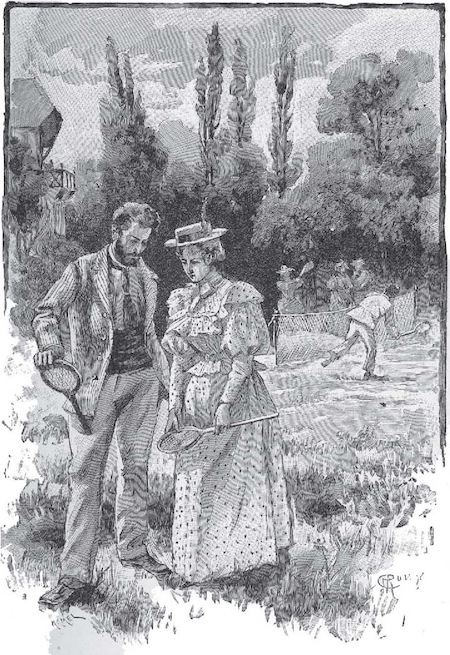

A FORTNIGHT later, on a smooth lawn in the beautiful grounds of “The Poplars,” gently sloping towards the banks of the Loire, might have been been a party of young girls in light dresses, and young men in striped flannels, engaged in a game of tennis. At a little distance in the background, near a red brick house, which had no pretension to be called a mansion, but which was of the simple and beautiful proportions of a comfortable modern dwelling, the older people were chatting round a tea-table. The mistress of the house, with her sweet face, and beautiful white hair, was occupied m paying hospitable attention to the wants of everybody. Madame Caoudal was radiant. She had her René with her, the object of her continual thoughts, her pride, her hope, the only one spared to her of all those dearest to her, By a happy chance the cruel extremes of mourning and of joy had been spared her motherly heart. No one had been in a hurry to impart to the poor widow the death of her only son; so that she heard, at the same time, of his accident and of the unexpected turn of fortune which restored him to her. Even with this happy denouements she had been much shaken, and her young favourite and counsellor, Hélène, had much difficulty in cheering and comforting her. The tearful mother had exclaimed against the cruel sea, which had robbed her of so much, and which would hardly let her keep her only son. But Hélène had hastened to point out to her that René was, after all, safe and sound, and, for that matter, to die in bed is less glorious than at sea (witness those neighbours of theirs upon whom their roof had suddenly fallen one night), and that it was all the greater pleasure to see him again after his terrible adventure. Whether her reasoning was bad or good, it succeeded in raising her aunt’s spirits; and, moreover, when she saw her René again, the best and handsomest son in the world, according to the excellent woman, she forgot her troubles. Tall, athletic, with a proud poise of the head, a martial bearing, frank and commanding eyes, his movements supple and graceful, Ren^ Caoudal was, in truth, a fine young sailor; one to satisfy the most exacting motherly pride. He returned, it is true, somewhat thin and pale, but that did not make him the less interesting to the young folks assembled to do him honour. On the contrary, among the tennis players, there was a remarkably increased assiduity in according him a gracious welcome. But apart from the ordinary courtesy due from him to all the guests as son of the house, not one of them could natter herself that she received particular attention from him. In vain the freshest of toilets had been put in requisition; in vain the most nattering words and. rippling laughter had been discharged at him; they read in his preoccupied look, his voice, his gestures, in his manner altogether, a sort of absent-mindedness.

“He isn’t like the René that he used to be,” said little Félicie Arglade, between two blows of her racquet. “He is changed somehow on the voyage! He has no eyes or ears for any one but Hélène.”

“After such terrible dangers,” put in Doctor Patrice, quietly, “with whom should he wish to talk but his cousin, his old playmate?”

“For my part, I have never believed in these marriages between cousins,” said Félicie, in a still quieter voice.

“But why are you in such a hurry to marry them?” inquired Mademoiselle Luzan, a tall, fair; sweet looking girl with a grave expression. “If I know Hélène, M. Caoudal is the last person in the world it would enter her head to marry.”

“Why are they always whispering in corners:hen?” retorted Félicie, somewhat softened.

“They are not whispering!” protested Mademoielle Luzan; “they are chatting confidentially.And what is there remarkable in

The cousins.

that? Do you not know that M. Caoudal has just narrowly escaped death? Wouldn’t you, if you were Hélène, be anxious to know every detail of his adventure?”

In reality, without any one being able to accuse them of whispering, as Félicie said, it was evident that Hélène and René had plenty to say to each other; and it was not, in truth, surprising that those who were not in their confidence should infer something strange. And how came it that Madame Caoudal, who had heard the whole story from him, and Stephen Patrice, who had heard it first, were neither of them recipients of these later confidences? Why was Madame Caoudal so radiant and Doctor Patrice so doleful? Was it that one of them saw the realization of her hopes, and the other, that which he had so long feared?

“This accident has touched their hearts and drawn them together,” said the good lady, “Sometimes good comes out of evil.”

“Undine will have to give way to Hélène,” thought the doctor, sighing. “Well, so much the better! It wouldn’t do to play the part of the dog in the manger, and one ought to rejoice in one’s friends’ happiness.” They were both a little hasty in their conclusions. The subject of these confidences between the cousins, which they pursued in the woods, at the river bank, in the drawing-room, and at tennis, was the inexhaustible discussion of the details of René’s adventures. On his return home, in the midst of the excitement, and the tearful joy of his mother, he had not been able to restrain himself from telling the whole story to her and to his cousin. For the subject had been tacitly ignored between him and the doctor, Caoudal having felt that his friend, if not hostile or sceptical, showed at least marked repugnance to encouraging him to speak of it.

As time went on, he became more and more animated and possessed by it, and, as the need of speaking and acting became more imperious, he showed that his heart was filled with thoughts of his mysterious acquaintances. Madame Caoudal appeared not incredulous, but displeased, cold, and even severe; she begged him seriously never to mention the subject in her presence again. Hélène never said a word, but her sparkling eyes spoke volumes; and when René, disappointed and perplexed, sought support and sympathy from her, she made him a sign to change the subject. “ Later, when they were seated under the great poplars which gave the name to their home, she explained her attitude:

“No need to torment auntie with the account of this wonderful adventure, or to let her brood over the projects that I understand,” said she. “You know what a grudge she bears to the sea; it is like a personal hatred between her and the liquid element. I believe she really thinks it a cursed power for evil. After the great sacrifice which she made in allowing you to enter the navy, we ought not to distress her any more than can be helped. If she believed, if it were possible for her to realize, that the depths of the sea, as well as its immensity, attract and claim you, that you feel called to the perilous honour of exploring unknown, mysterious, it may be deceptive regions, she, poor, dear soul, could not live. Spare her that distress.

“She has forbidden you to speak to her of such things. Obey her implicitly. As for me, I enter henceforth into all your plans; you know I have always shared your ambitions. Sometimes, nay often, I dream that I, too, pursue the glorious career of a sailor; I feel through my hair the vivifying air of the vast expanse; I fancy myself commanding a vessel; I see myself facing, with our brave seamen, the fury of the gale, landing on unknown islands, discovering new plants, new animals, new wonders, changing the aspect of geographical charts—and I wake—Hélène Rieux, as before!

“Do not think that I complain of my lot! But I admire and revere the glorious profession of my grandfather, of my uncle, and of yourself, and I shall be as proud of your exploits as if they were my own. All this is enough to show you that for these projects, still unformed, still indistinct, you should not seek any confidant except myself. You cannot be too careful. One only understands perfectly what one loves; and I feel strongly, myself, that nothing but a peculiar, hereditary influence could induce me to believe unhesitatingly and with absolute certainty in your veracity. Like other people, I see much that is incredible in your adventure, and yet I believe in it- That which convinces me is not, as with Stephen, my confidence in your good faith, the conviction of your clearheadedness, or even the proof of the ring. No, it is ‘the eye of faith’ voilà tout. It seems to me that it must be; because when one is a born explorer, one goes straight at the discovery; because you have been called to see that which others could not see. In short, I believe, because I believe!”

Nothing could be more satisfactory than a confidant of this sort, and René was not less anxious to tell than she to listen. Away with the false conclusions of Madame Caoudal, of Dr. Patrice and of other friends! Hélène and René, like accomplices, continually felt the need of some mysterious confabulation. Either René had omitted to give in detail some one perfection of his goddess, or else Hélène had some new hypothesis to suggest, or wished to be told over again some forgotten circumstance. And, above all, there was the increasing importance of the question:

How to find the enchanting abode of these august personages again? How to find the time, the means, of attempting it? How to do all without awakening any suspicion on the part of Madame Caoudal? Hélène was firmly resolved on two points: to spare René’s mother all uneasiness, all useless anxiety; and to encourage, as far as lay in her power, that which she considered to be the fulfilment of a duty, a chosen mission.