asha and McGloury rode a gig, a one horse, two-wheeled cart, up a slight incline on a very bumpy dirt road. McGloury halted the horse and pointed below them. “There it is, lass. My bonny wee croft.”

asha and McGloury rode a gig, a one horse, two-wheeled cart, up a slight incline on a very bumpy dirt road. McGloury halted the horse and pointed below them. “There it is, lass. My bonny wee croft.”Chapter Eleven

The McGloury Croft

asha and McGloury rode a gig, a one horse, two-wheeled cart, up a slight incline on a very bumpy dirt road. McGloury halted the horse and pointed below them. “There it is, lass. My bonny wee croft.”

asha and McGloury rode a gig, a one horse, two-wheeled cart, up a slight incline on a very bumpy dirt road. McGloury halted the horse and pointed below them. “There it is, lass. My bonny wee croft.”

To a Scot, almost everything was “wee.” I once heard a Scot call the gigantic ocean liner Queen Mary a “wee boat.” However, McGloury was being more accurate than colourful. There was a thatched roof cottage near a sheep pen clustered close to a cliff with a mean drop to the water below.

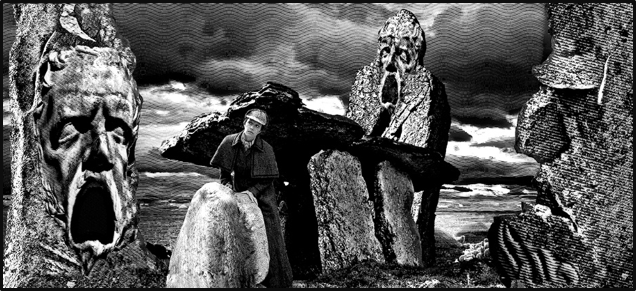

By day, the place was more picturesque than sinister, but there was something else. About fifty yards from the cottage, adding a bizarre touch, were a group of ancient pagan ruins.

They were tall, rectangular dolmens, arranged in a semi-circle around an altar, crudely carved with agonized and brutal human faces, an eerie blend of Stonehenge and Easter Island.

Tasha was pleased at this eldritch stage upon which she found herself a major player. “Lovely, Mr. McGloury. A worthy setting.”

In front of the croft, near the sheep pen, a thickset man with stiff bearing sat astride a horse. The rider was arguing with a young man in working clothes and a long wool vest, who gestured wildly. Standing beside the horse and its expensively attired rider, were two burly field hands. On a signal from the mounted man, one grabbed the young man and moved him away from the sheep pen’s gate. The other of the big men held a sheep on a rope leash.

McGloury scowled, “There’s trouble! That’s Laird MacGregor! And they’re accosting my ghillie Tom!” Tasha knew that a ghillie was Scots for a croft’s hired hand, and that Laird MacGregor would be called Lord MacGregor south of Hadrian’s Wall.

She held on as McGloury flicked the reins, sending the cart gamboling toward the croft. He pulled to an abrupt stop, jumped out, and ran toward the Laird. Tasha stayed behind in the cart, observing.

The Laird pointed his riding crop at McGloury, “You’ve been caught clear and fair, McGloury! Alec! Show him! Sean, let the lad loose!”

As the Laird turned his face, Mother got a good look at him. Tasha was not an easy mortal to surprise, but this revelation caught her genuinely unawares. It was none other than “Captain Crocker” from the Inn of Illusions. The same man who had leapt out the window of the Cunard Room when interrupted by Ramsgate. The Laird—and Mother would have to cease thinking of him as the imaginary “Captain Crocker”—hadn’t spotted Tasha, as he was signaling his men. Sean let Tom loose and Alec brought forward the sheep. Tom, the ghillie, rushed to McGloury.

“He wants to look o’wer the flock. I dinnae let him.”

“Good lad,” said McGloury, still glaring at the Laird.

The Laird merely cocked his head toward the sheep, “Look at your mark, McGloury—go on, man. Use your eyes!”

McGloury inspected the dye mark, the “brand” on the sheep. It was blue, but tinted red unevenly around the edges.

“Do you see the red, now?” demanded the Laird.

“Aye! There’s nothing wrong with my vision!”

“And do you recall that my mark is red?”

Tasha just watched, enjoying the confrontation. McGloury shoved the sheep away and spun to the Laird, towering above him on his horse. “Listen to me, Laird MacGregor. You may own the best land on Millport, but you dinnae own this croft, you dinnae own me sheep and you dinnae own me! So a good day to you!”

“You deny that this sheep is mine?”

“Man, I deny nothing! But it’s travelling overfast to accuse me of thievery!”

“Half the flock in that pen have, or had, my mark! Alec! Sean!” At his signal they moved toward the sheep pen. McGloury and Tom tried to block them but the struggle was brief as the bigger men tossed them aside. While they did that, Tasha walked to the pen’s gate, leaned against it and folded her arms, strategically lowering her head so that her wide hat hid her face. Alec and Sean approached her, but not wanting to assault a lady, gestured to their Laird for guidance.

Laird MacGregor, not recognizing Mother with her face hidden, tried to be civil. He asked her to step away from the gate. With her pugnacious visage masked by her hat, she shook her head. MacGregor altered from polite to persuasive, as he barked to the larger of the two men. “Alec, move her! Be gentle … if you can!”

Alec nodded and grasped Tasha’s arm. She spun and smashed him into the fence. He stumbled to his feet in amazement. “I slipped! You aw’ saw that!”

“Of course you did,” offered Mother as she grabbed him and flipped him into the sheep pen. Sean, the smaller of the Laird’s men, moved forward carefully. Tasha crossed her arms and grinned challengingly at him. He came close and, with hesitation, stretched out his arms to lunge at her. Mother directly eyed MacGregor, smiled and said, “Captain Crocker, I presume.”

Laird MacGregor could barely get out the word “Stop!” rapidly enough.

Sean, arms still poised to grapple, stood fast as MacGregor reached into his coat pocket and withdrew a pair of glasses, bent closer and stared at Tasha. “Eliz—” He cut himself short.

Mother cocked her head. “Stroke.”

MacGregor wheeled his horse around and shouted to his men. “Come away, lads. There’s work to attend to.”

Tasha leaned back against the fence as Alec climbed out of the sheep pen and strode wrathfully over to her. “You havenae heard the end of this.”

MacGregor cut him short, ordering him back to the manor. Alec gave Mother a final glare and stalked to the Laird. MacGregor cocked his head to get going, and his two men headed down the road.

MacGregor paused and leaned closer to Tasha. “You don’t think you could have mistaken me for someone else?

“A mistake is always possible.”

“Very possible.” He responded with a threat in his voice as he moved toward the road, passing McGloury. “I can’t stop you living here, but stay away from my flock.”

Tasha walked closer, “If you have a problem, there’s always the police.”

MacGregor laughed at that and galloped off, soon over-taking his men.

McGloury, with an air of satisfaction, shouted to Mother’s enjoyment, “And dinnae come back! Tom, fetch the lady’s things.”

Tom got Mother’s bag from the cart and hefted it to the cottage. Tasha inspected the surroundings one more time. “I take it Laird MacGregor wants your croft and you declined to sell it.”

“Aye.”

“It’s curious that you are losing sheep and he thinks you are stealing his.”

“There’s not much grazing, flocks get mixed … but you and Laird MacGregor seem to know each other.”

Tasha merely shrugged. “We might have crossed paths on holiday.”

McGloury snorted. “Aye. With a wife like his, I’ve no doubt he needed one.” He held open the door as they entered the cottage.

That night, against the sunset, the tall crumbling stones seemed even more abnormal. Tasha ran her finger over the craggy lips of one of the granite faces. Something caught her eye. There was a crescent-moon carved into one of the monoliths.

“We’ve met before … somewhere …” mused Tasha.

All around her, a thick fog started to roll in from the firth. Within the hour, one could barely make out the feeble light of the cottage from the ruins.

The cottage was a sparse, two-room affair with a stone fireplace, big iron swing kettle and up-to-date furniture. It was quite comfortable. They had finished their supper of penny potatoes and haggis. Tasha and McGloury sat—at Tasha’s insistence—in the most uncomfortable chairs McGloury owned. Her strategy was only partially successful, for although Mother was awake and alert, McGloury was snoozing.

Then Boab, McGloury’s collie (of the teeth-marks-on-the-walking-stick fame) stirred, aware of something, and started to whine. Tasha turned down the lamp as Boab barked more intently and clawed at the door.

Outside, something was agitating the sheep. They shifted back and forth in the pen, pushing against the wooden fence.

Tasha, her eyes gleaming, and McGloury, awakened by Boab’s barking, both rushed to the window. They saw that somehow the sheep pen gate was open—but the flock wasn’t stampeding. A few sheep near the gate wandered out, but most of the flock stayed in the pen.

McGloury, fearing for his livelihood, raced out the door, with Tasha directly following. Tasha ordered him back to the cottage, but he refused and dashed to the pen, slamming the gate shut, while Mother chased the few of the flock that had escaped. She had valuable assistance from Boab. The collie knew his business and ran and barked, herding the sheep.

“Look out for the cliff!” shouted McGloury as Mother ran in that direction. The warning would have been better intended for the sheep, for a few of them tumbled over the cliff to the invisible sea below. Tasha lunged for one lamb about to fall over the edge. She pulled it by the leg and dragged it to safety, then carried the bleating animal back to the pen. With Boab now quietly at his side, McGloury accounted for his sheep. Tasha let the lamb into the pen as McGloury closed the gate.

The night was suddenly deathly quiet. Tasha studied the ruins—no more than a dark vagueness in the fog.

“I cannot protect you if you disobey me!” said Mother sternly. McGloury gave her a contrite nod, and Tasha, McGloury, and Boab walked back toward the cottage when a new sound drifted across through the fog: a mournful wailing, feminine, eerie, and sad, coming from the ruins. Standing amid the stones, and hardly distinguishable in the mist, was the lone figure of a shrouded woman, seen and vanishing at the whim of the fog. The spectre’s skull-like face was barely visible, and her haunting wail beckoned.

Tasha was not easily convinced of apparitions. “That’s a lot of wind for a ghost.” She moved toward the ruins, but McGloury, terrified, grasped her arm. Tasha broke free. At that moment, the wailing ceased and there was only silence.

The ruins were empty.

Tasha scowled at McGloury for interfering with her, but as he was so shaken, she softened and said quietly, “You’d better go inside.”

He nodded, and they walked to the door, but Boab barked at something toward the ruins. Tasha stared into the mist and listened intently. An indistinct figure ran from the tall dolmens. Boab barked and growled. McGloury, sensing danger, grabbed the dog’s collar to hold him.

The figure suddenly screamed a woman’s scream and staggered. Tasha heard a muffled, hoarse cry that seemed to say “Deirdre!” Then the figure screamed in pain, lurched to the cliff and, shrieking, flung herself over the edge.

Boab broke free of McGloury and dashed into the fog. Tasha cautiously moved to the cliff and gazed over the edge, noting how it disappeared into the mist below. The crashing of the surf was markedly audible. McGloury came up behind her. “Who is Deirdre?” asked Tasha.

“I dinnae ken.”

Mother nodded and they walked back toward the light of the cottage. McGloury called for Boab, but was answered only with silence. He called again. “Now where is that dog?” They both searched the fog for him. “It’s not like him to not come,” worried McGloury.

Tasha’s eyes fell upon the ruins, grim and silent in the swirling mist. She realised how exposed they were out in the open. “Look for him in the morning,” she advised.

Her sense of danger was communicated and McGloury did not argue.

As they walked back to the cottage, they were being watched from a tiny hole atop one of the dolmens, high above unaided reach. The hole, through a series of tiny tunnels and mirrors, sent a shaft of light deep underground.