I nudged Tumbleweed to the edge of the drop. The front tracks squealed in the mud, lost traction, dug in again. Trusting the brakes but not the terrain, I tossed a couple of anchors aft. Tumbleweed settled, motors back-hammering, ready to ride.

I closed the cockpit and opened a line to the Wishbone Outpost.

'You there, Jeke?' I said.

'Where else would I be?' Jeke had the temper of a turtle. With a powder storm brewing, he got snappier than ever. But he ran the outpost single-handed, so when I fetched up there he was all I'd got. 'You know, Tanager, you didn't finish your soup.'

'Chicken gives me wind.'

'When a person goes to a lot of trouble for another person, the least that person can do is eat the chicken soup.'

'Look, Jeke. I appreciate you putting me up. You keep the outpost nice. I like the doilies. But I'm on a schedule here. Keep the damn soup warm - I'll eat it next time. Right now I need a forecast. You got one?'

'Oh, so what am I now? Your pet weather man?' Just what I needed: a turtle in a sulk.

'I think you're the only guy can tell me it's safe to steer my payload off the edge of this world and into the jaws of twelve different hells.'

'Tanager, as usual you're misrepresenting the facts. As you very well know, the concept of hell is purely ...'

'Just give me the forecast, Jeke.'

Static choked the board. Jeke's voice turned to mush. I thumped the transmission box. The mush turned to bubbles; inside the bubbles I heard two words:

'... love you.'

After that, it was just the static. I hit the box again. The static cleared, but Jeke was gone.

My surprise hung around.

I checked the back window. The outpost was just visible through the murk: a squat column of white stone. The top quarter was all lookout glass. A tall silhouette brooded behind it.

'Timing was never your thing, Jeke,' I muttered, 'but I got to say that was a real doozie.'

The murk swallowed the outpost. A full-blown powder storm crashed in. Goodbye comms. Volts jumped from one dust particle to the next to the next, turning the sky to a brilliant cobweb.

I went to the front of the cockpit, looked down at the drop.

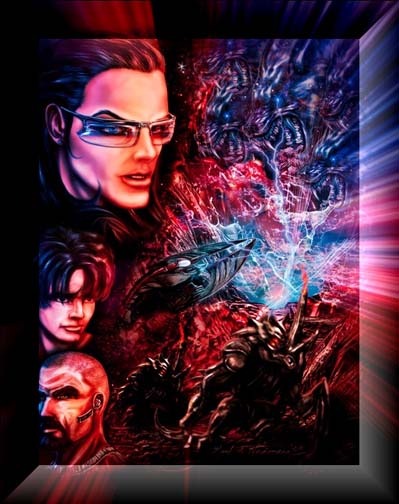

Tumbleweed was perched on the edge of a vast abyss. The abyss was a hole in just about everything. Looking down it was like looking down a well - a well big enough to swallow Jupiter. The god, not the planet. The god's bigger. I've seen him.

Whatever world you're in, the drop looks the same. Pour sulphuric acid down your throat, the drop's what your throat looks like after. There's rips in space, rips in time, the raw torn seams of over-buckled branes. Tattered lengths of cosmic string hanging limp like cat-clawed knitting. The drop's an abomination, somewhere no sane person would go.

And here I was hanging off the edge in a bruised-up dropship with only a pair of Rickenbach anchors lodged in mounds of sticky mud to stop me falling off the end of the outpost runway.

What a way to make a living.

Storm water poured past Tumbleweed's tracks, turned to foam where it hit the rips in reality. Turned to other things too, things with teeth and claws, things best not seen. I could hear them beating on the hull. But Tumbleweed's tough. She has to be. As for the rest of the runway - that was deserted. Nobody came here any more, except those crazy enough to do what I was about to do.

Crazy enough to drop.

A run of volts grounded a hundred yards away. The drop edge exploded; muddy bedrock showered into the abyss. It fizzed as it fell through slice after slice, turned to silver, to flesh, to a whip of orange light that cracked and vanished in the dark. Things change when they drop, change in ways you'd never think. Every time it's different; most times it's bad.

Lucky for me, Tumbleweed doesn't care for change.

I dumped myself in the front chair, revved the motors. Who needed a forecast? I'd only wired up to hear one last voice before I went over. Even one as snappy as Jeke's.

'... love you,' he'd said.

I popped the clutches, jerked the anchors loose, goosed the throttle. Tumbleweed's treads slithered, then bit. She tipped forward. Stale food rolled from under the pipes, across the tilting floor. The horizon climbed the window. Then the gimbal caught up and the whole cockpit was swinging like a fairground ride. There was a groan from the exoskeleton. The tracks retracted, foils deployed. Suddenly we were free of the mud, free of the edge, falling free through chasing volts and powdery light, falling into the drop.

The slices rushed past like floors in an elevator shaft, one after the other, each slice a hole in the bulk, a gateway to another place. Most were blocked with flotsam: shattered cities, mountains of soil and slops, the crammed bodies of hapless refugees. The worlds were shrinking out of the bulk and this chaos was the result. I let Tumbleweed fall, ignoring the dead, and the creatures that fed on them.

On the wall behind me, the clicker counted off the worlds at the rate of two hundred and twelve per minute.

... love you.

I kicked the throttle: time to really open her up.

There was a bang from the motor bay.

Tumbleweed shuddered, started corkscrewing. The clicker went crazy as the worlds bunched in. You start spinning in the drop, you find a whole new set of dimensions you never knew existed. I flinched as we glanced off the splintered edge of a recurved brane. Capillaries opened up all round, jabbing blacklight through the windows. The gimbal squealed once then shut down completely. The cockpit tossed me sideways. Tumbleweed creased down the middle, hit something hard, stopped.

The clicker fell silent. The cockpit rocked forward, then back. There was a thick grinding roar. The front window bulged until I was sure it would shatter. The glass straightened with a pop. Tumbleweed's foils sank inboard; out came the tracks. The hull trembled as they tried to bite down. But we were stuck between the strings. There was nothing to bite.

I was on the floor. My head felt like an egg. It was silent except for the odd clank as Tumbleweed cooled. The windows were fogged with cracks. I had no idea where we were. Limbo, or maybe Oblivion.

The cockpit floor hatch opened. The hinges creaked, fighting the warped frame. A young man - scarcely more than a boy - climbed up. He was followed by smoke and covered in oil.

'I'm sorry, miss' said the stowaway. 'But I think I might have broken your ship.'

* * *

He let me tie him to the chair. I cursed him as I tightened the knots. Over-tightened, just because I could. He didn't flinch, just took his punishment. If he hadn't, I might have killed him. I guess he knew that.

I closed the hatch, set the fans to dump the smoke. Ten minutes, I could get down there and check out the mess.

I sat on the helm and stared the stowaway in the eye.

'So spill the beans,' I said. 'Start with who the hell you are and finish with what the hell you're doing on my dropship. And I'll take a side order of where the hell you came from in the first place.'

'My name's Daniel,' he said. Long hair heavy with oil flopped over his brow. He flicked it back. 'And I'm really sorry.'

'Time for sorry's gone. It's answers I want.'

The floor dropped six inches. Tumbleweed was settling into whatever unimaginable mire she'd grounded in. I listened - I know what most things sound like against her hull. I identified teeth.

Daniel's eyes had widened with fear. 'Is it safe?'

'Nothing's safe!' I watched his lower lip tremble. He was very young. I relented. 'Okay, it's safe. For now. So talk.'

'Well, if you are going to help me I suppose it's only fair you should know all the facts.'

I didn't answer that one, just glared. It got him talking.

'I don't really know how I got here. I was following my dad and kind of got lost. My dad's been acting funny for the last few months, ever since my mum died. My mum had cancer. When it got really bad, she killed herself. She took a load of tablets and jumped in the canal. She left a note that said she did it for us, so we wouldn't have to see her suffer any more. My dad's ... well, I guess he's gone a little crazy.'

'Hold up,' I said. 'Too much, too fast. All this happening in the Wishbone?'

'What?'

'The Wishbone. That where you live?'

'I don't know what you're talking about.'

I went to the window, stared at the crazed glass. 'You know what the bulk is?'

Daniel shook his head. 'Never heard of it.'

'The bulk's everything. The ocean all the worlds swim in. Wishbone's one of those worlds. The place we just came from, the place you hitched a lift. So I'm guessing it's where you live. Savvy?'

'Why do you call it the Wishbone?'

I picked at the cracks in the glass, wishing I could see through it. 'You're the one telling a story here. Get on with it.'

* * *

'Dad always walks the dog after supper. She's a Red Setter, a real beauty. Her name's Mizzy. After mum died, the walks started taking longer and longer. Sometimes he'd be gone two or three hours. And I mean there's nowhere to go round where we live - it's just streets and skateboard parks. It didn't bother me at first - most evenings I'm busy with college work - but pretty soon I found myself watching the clock, waiting for the door. One night he was out for over four hours, didn't get back until gone midnight. When he came in he was soaking wet. Mizzy was caked in mud and all scratched down one side, as if she'd run through brambles or something. And this is in the middle of the city, in the middle of summer. There's been a drought. It hasn't rained for months.

'I asked him where he'd been but he just told me to mind my own business. He's a big man, my dad, and I've never had the courage to cross him. He put his clothes in the washer, told me to clean Mizzy up and went to bed. Later, when I went up myself, I heard him crying in his room.

'So tonight, when he went out, I followed him.'

Daniel paused, shifted in the chair. 'I'm sorry,' he said, 'but these knots are really tight. Is there any chance you could ...?'

'Keep talking,' I said.

He went on. 'I kept to the shadows. It was hard, because the streetlamps are so bright. When you live in a city, the night sky's orange. There's no stars. Anyway, I followed my dad through the underpass to the canal. I hate the canal. Not just because of mum. Nobody goes down by the canal at night. Christ, even in the day most people avoid it. People get attacked down there, but mostly it's just ... just creepy. Everything down there feels wrong, you know?'

The teeth outside had started chewing on the hull. But the boy had my attention. 'Wrong how?'

Daniel shuddered. 'I don't know. There's a smell, like toffee burned to a pan. And there's always a wind blowing, even when everywhere else it's calm. The whole place feels like ... it feels like a scab on an old cut, you know? It tingles. It feels like ... like something's getting ready to pick it off - to pick you off - and expose the new flesh growing underneath ...'

He broke off. He looked ready to cry. I felt sorry for him: a bashful boy tied to a strange woman's chair, scared she wouldn't believe his fairy tales.

'I know exactly what you mean,' I said.

He took a deep breath, said, 'I followed my dad down the towpath to the lock. Half a mile or so. When he got there, he tied Mizzy's lead to one of the bollards and started shouting at the gates.'

'Gates?'

'The lock gates, you know.'

'What did he shout?'

'My mother's name. He shouted it again and again. He was leaning right over - I thought he was going to fall in. But he didn't. Mizzy was barking her head off, pulling at the lead. Dad just kept on shouting. So I crept closer. That's when I saw it.'

The chewing sounds were getting louder. The fans were still pumping. I checked the board: five minutes before the smoke cleared. Good job the hull was tough.

Time enough for the kid to finish.

'What did you see?' I said.

'A window.'

I never knew your ears could actually prick up. They can. 'Window?' I said.

'Yes. Set into one of the lock gates. A window, like a window in a house. It was low down, half-submerged. It was only visible because the water level was so low - you remember I said there's been a drought? Anyway, suddenly my dad stopped shouting and jumped into the canal. The water only came up to his knees. He went up to the window, bent down, put his hands on the frame, started shouting again. I saw someone on the other side of the glass. That's when I knew I had to be dreaming.'

I went close to Daniel. 'That why you're so calm? Because you think all this is a dream?'

He blinked guileless eyes. 'Isn't it?'

'What happened next?'

'My dad opened the window and climbed through it.'

'Climbed through it?' I stared at my captive, intrigued. 'What did you do?'

'Nothing at first. I froze up. Then I went to where Mizzy was and untied her. As soon as I did that, she jumped off the towpath and into the canal, just like dad. Only she didn't land in the water - she landed on it, like it was concrete. The burnt toffee smell was much stronger now. The air was sort of ... crackling. I shouted to Mizzy but she didn't take any notice. So I thought, "What the hell," and jumped after her. It was a dream after all.

'The water was kind of spongy, a bit like that rubbery stuff they use on kids' playgrounds. It didn't seem to bother Mizzy that she was walking on water. It bothered the shit out of me though. I saw the lock gate had opened. Mizzy ran into the lock and out the other side. I chased after her. Eventually I caught her up. We weren't walking on water any more - we were on a wide muddy road. The city blocks were gone. I couldn't see much of anything really. The sky was dark and full of clouds. I saw a building up ahead. It looked a bit like a lighthouse. It started raining. I dragged Mizzy through the mud to the building and knocked on the door. A tall man let me in. He said his name was Jeke. He was putting on boots, getting ready to go out. When he saw me, he changed his mind. I could smell chicken soup. He took us in and fed us. The upstairs room was full of all this weird equipment, like the inside of a submarine or something. I was dazed, didn't really know where I was, or what was going on. Jeke told me I'd lost my way, but he knew how to get me home. He pointed through a window at this thing lying in the mud. It looked like a giant lobster. It was hanging off the edge of a precipice. He said it was a vehicle about to set off on an important mission. He told me if I delivered something to the pilot for him, he'd get me home.'

The kid had lost himself - a kind of total recall. Now he was coming out of it. He blinked like he'd just woken up.

'Could you free my right arm please?' he said. 'Just for a minute. Then you can tie it back up again if you like.'

He looked so sorry for himself I did what he asked. When his right hand was free he used it to pinch the flesh of his left arm. He flinched, did it again. 'I'm not dreaming, am I?'

Outside, the chewing stopped. Something hit Tumbleweed like a dozer. Nasty harmonics shook the subframe. The something bellowed. I slipped the rest of Daniel's knots, let him stand up out of the chair.

'You're letting me go?' he said.

'Right now you're the least of my worries. Plus maybe you can help.'

'If I do, can you get me home?'

'We'll see. First we got to get out of this.'

There was a double thud as a second bellowing thing ploughed into the hull. Daniel and I hit the back wall together, bounced into each other's arms. He held me tight. Convincing himself I was real.

'What's out there?' he said. Green lights flashed on the board.

'We get Tumbleweed fixed, you don't ever need to know. Now show me what you broke.'

I grabbed a toolbox, popped the hatch, followed him down the ladder. The smoke was mostly gone; it was still like plumbing a volcano.

'Oh, this is what Jeke gave me to give you,' Daniel said when we reached the bottom. He was holding a little red box. He pressed it in my hand.

I opened the box. Inside was a little velvet cushion. On the cushion was a gold ring. In the middle of the ring was half a ruby.

'Was there a message?' I said. My throat was all choked up. Probably the smoke.

'No message,' said Daniel. 'Just the ring.'

Tumbleweed screamed. Something was trying to peel her like an orange.

'Let's get to work,' I said.

* * *

I'd been wondering how the kid got aboard. I keep Tumbleweed wrapped up pretty tight, especially when she's about to go over. Not as tight as I'd thought.

'There's a sort of access panel,' Daniel said when I asked him. We were in the motor bay now. The air was like black porridge, despite the fans. The floor was slick with oil. 'Here it is.'

Coughing, he knelt. The floor was popped open. A sliver of light crept in through the break in the hull. Alarming, but I was more bothered by the shadows moving on the other side of the break.

'I tried to close it, but it wouldn't latch. I sort of forced it and I think a pipe broke. That's when everything went wrong.'

It wasn't the first time Tumbleweed had surprised me. We'd been riding together two years now and there were a hundred crannies I hadn't explored.

'Jeke tell you about the secret passage?' I said.

'No, but he did suggest I find an alternative to the front door. He thought if I just knocked you wouldn't let me in. I suppose I just got lucky.'

'Matter of opinion,' I muttered.

I put down the toolbox, picked out a spanner. The pipe wasn't broken, just pulled from its socket. I pushed it back, tightened the grubs.

'Six minutes, we're out of here,' I said. I hooked a wrench on the rogue panel, pulled it shut. Just before it latched, something crashed against it, snarling.

'That's what I've been meaning to ask you,' said Daniel. 'Where exactly is here?'

* * *

Back in the cockpit, while the motors rebooted, I gave him the short version.

'The place you live,' I said, 'isn't the only place there is. That feeling you described? The one you get down by that canal of yours?'

'What, that the whole area feels like a scab?'

'Yeah. That's not bad. World as scab - it's only when you pick it away you get to the real meat. Well, that's where we fetched up: the meat between the worlds.'

Daniel was trying to see through the crazed front window. 'I'm not sure I understand.'

'Okay, look. First off, there's more worlds than you can count. Each world's connected to the next. It's like bones in a skeleton. You know, the toe bone's connected to the ankle bone? Only this skeleton's got more legs than you've had wet dreams. And like any skeleton, it's surrounded by flesh. In this case, the flesh is called the bulk. The bulk's everything that exists outside the worlds. It keeps the worlds cushioned and fed. In return the worlds stop the bulk flopping like a custard.

'Only trouble is, the bulk got sick.'

I could see him wanting to believe me. He'd turned from the window; he was studying the patch of red skin where he'd pinched himself. Behind him the glass was starting to clear. Rejuvenation's one of Tumbleweed's neater tricks. I hoped he wouldn't look round again. Now the things outside were coming into focus, even I was getting twitchy.

'What do you mean,' he said, 'got sick?'

I checked the motors. Nearly there. Visible through the half-cleared glass was something like a sunset. Or a huge fire. Shapes like soft factories were loping through mountains of flame. Closing in.

'Let's just say things are going to pieces. There's cracks in the bulk. If it really were a body, it'd be coming apart at the joints. That puts strains on the bones trying to hold it together. Strain on the worlds. It's why you were able to punch through to the outpost, walk on water even. Places like that canal of yours - they flag the weak spots.'

One of the factory-beasts slammed its horns into Tumbleweed's flank. Fire burst from its blowhole. A vertical row of two hundred eyes blinked in a funky Mexican wave.

Daniel turned to look, and screamed.

The glass had cleared, revealing giants that were half fungus, half architecture. One looked like a power station, or a rhinoceros. It bit the head off its neighbour and tossed it towards the window. A flying horn hit the superstructure, threw Tumbleweed on her side. Alarms shrieked. We crawled over the walls, grabbed the chairs, strapped ourselves in with heads down and feet up. I stretched for the helm, punched the drop sequence. Shut my eyes.

There was a jolt as something serpentine hit the hull. A tail lashed, shedding scales like puffball spores. Tumbleweed self-righted, lunged for the drop, trailing flames. The snake-thing dropped coils on her tail, dragging us down. I deployed the anchors; they hit like scorpion stings. The snake-thing fell back, writhing. The pull on the anchors killed our momentum so I cut them loose. Tumbleweed sprang forward, took the edge like a gazelle, sliced her way into the drop and we were falling again, motors whistling, falling clean and free.

* * *

Daniel was quiet for a long time. I left him to brood. There was work to be done: cleaning up, checking Tumbleweed's criticals, replotting the Juncto trajectory.

I lost myself in the work. It was good to get dirty, work up a sweat. We'd had a close call - not as close as some, too close for comfort. It was an hour before my hands stopped shaking.

Getting too old for this, I thought.

Turned out the motors were running sweeter than ever. Looked like that pipe had been leaking a while. Maybe the kid had done me a favour.

When I'd finished degreasing the floor, I sat in the shadow of the motors. It's my favourite spot for a break. The motor housing's like a cathedral: twelve storeys of chains and crystal and crazy spinning looms. How it works I couldn't say. I just trust it to go and it does. Trust's a big part of what we do together, Tumbleweed and me. Without it, we'd be nothing.

Jeke now. He was a different fish. With Jeke, trust didn't come into it.

I looked at the ring he'd sent me. A single ruby, cut through the middle. No prizes for guessing who had the other half.

What a sap.

The ring was beautiful. Trouble was, it didn't add up. Jeke had never given me the first clue he felt this way. The opposite, actually. Whenever I turned up at the Wishbone Outpost - which was maybe six times a year, tops - he just fed me soup and gave me a hard time. Smokescreen? Hiding his true feelings? Not how love's meant to be, not in my book.

I shut the box without trying on the ring. I knew it would fit. Jeke would have got that much right.

A shaft of light swung across the motor housing. Daniel stood in the hatch.

'Now that we're safe from those ... things,' he said, 'I wanted to say I think all this is pretty cool. I mean, it's like dimensions or something, isn't it. You and your ship. You travel between worlds!'

I shrugged. 'It's a living.'

'Only, I was thinking. When I was telling you about my dad and what happened at the canal, you were only half-listening, like you'd heard it all before. Right up until I mentioned the window in the lock gate.'

'What did I do then?'

'Your ears pricked up like Mizzy's when she smells a rabbit.'

I stuffed the ring box in my pocket. 'So what?'

'So I think you really do know how to get me home. I also think you know what happened to my father.'

I said nothing, just stared up at the spinning looms of Tumbleweed's motors.

'Will you tell me what you know?' he said. 'Please?'

I stared at him, a young man both brave and scared. The best combination. He reminded me of someone I knew, a long time ago.

'Come with me,' I said. 'I want to show you something.'

* * *

Tumbleweed's built like a lobster. Looks a bit like one too, when you get past the retractable treads and foils and all the thousand and one bolt-ons that turn her from regular bulk clipper to bona fide drop-ship. All her hard parts are connected by soft tissues. The cockpit springs directly off the motor bay, but everything aft you get to through soft veins and ventricles. It's hot and damp and spongy.

To my surprise, Daniel loved it.

'It's like a living ship!' he said. We were in the dorsal artery, heading aft. The walls hugged our shoulders; the air was tropical. 'Is it alive? Does it think?'

'Tumbleweed's a capsul,' I said. 'Oldest rolling stock there is. Capsuli were built for pleasure - soft cabins and big brains. They were strictly hands-off, smart enough to run themselves, leaving the passengers to do whatever took their fancy. Trouble was, they had a knack for going crazy.'

'Crazy?'

'Building intelligence is easy. Building sanity - that's something else.'

Daniel shrank from the cloying wall. 'Are you telling me we're inside a robotic ship with the mind of a lunatic?' he whispered.

I rounded on him. 'First,' I said, 'she's no robot. She's as real as you or me, and don't you forget it. Second, she's not just a ship. She's a dropship, and more than that she's a capsul. Trust me, that's makes for a whole heap of special. Third, she's not crazy, not any more.'

'But you said ...'

'I know what I said. Only reason I took up with Tumbleweed is she's one of the few capsuli not sat in some scrapyard mumbling to herself. When she learned what was likely to happen to her intellect, she took precautions.'

'What do you mean?'

I touched the wall. It enveloped my hand, squeezing me with warmth. 'She had her mind reduced.'

Daniel watched Tumbleweed envelope my arm. He looked revolted and fascinated at the same time. 'Reduced?'

'Tumbleweed's like that big drooling kid you see at the play park,' I said. 'You know the one? She's slow. She looks funny. She does the same thing over and over - kind of like an OCD thing.' I pulled my arm free, went right up to Daniel, looked him in the eye. 'But when you trip over she's first there to pick you up. She hugs you all the way home and whatever you say to her, she tells you she loves you.'

The kid stood there a minute, not looking away. Then he smiled.

So help me, he understood.

We pushed through the artery to the far aft hatch. The kid was eager to see what was on the other side. I let my hand linger on the switch.

'World-hopping's okay,' I said, 'but it's hard work. Plus it's dangerous. Seen that for yourself. So you need good reason to do it at all.' I swung the hatch open. 'Here's mine.'

* * *

The hatch opened on Tumbleweed's hold. The hold takes up half the hull. It's full of windows. Not so's you can see out - these windows are cargo. They're stacked and tagged, like racks in a warehouse. We stood on the catwalk, overlooking them all.

'Six thousand and seven,' I said before Daniel could ask. 'They come in pairs, but I'm mid-run so right now there's an odd number. Each window marks the end of an interbrane capillary. You watch science fiction shows? Think wormhole. Each run I make, I drop a window in one world, take its twin to another. The windows are entangled, so stuff can move through the capillary, between the two worlds. The connection's made, I move on to the next job.'

Daniel's eyes were roaming the hold. I keep the windows shuttered but there's always glints of light poking through. There's all kinds of stuff behind those windows, a lot of it keen to get out. A lot of it you don't want to see.

'It's incredible,' he said. 'But what's it all for? It seems to me you're a kind of ... well, you lay roads, I suppose. Or build bridges. But why? You say things move through these capillaries - do you mean people? Is it like a giant subway system?'

'Not the way you'd think. There's folks travel the tubes, but it's not an easy ride. Messes with your mind. Mostly they use the windows to move resources. This world's got iron, that world needs it - you shift the ore through the window. Oil's a common payload, so's livestock. Ordinary commodities. The tech's exotic, but most trade just comes down to keeping warm and keeping fed.'

Daniel's gaze landed on the window at the front of the stack. It sat alone, draped in foil.

'Is that the one you're getting ready to deliver?' he said. 'Where are you taking it?'

'Place a long way south of here,' I said. 'One of the old worlds. Place called Juncto. That window under the foil - earlier today I left its twin on the Wishbone, your world. I get to Juncto, drop this one off, I get a full tank for Tumbleweed and a crate of canned meat for me.'

'Is that all they pay you? Don't you get money?'

'Like I said - you keep warm, you keep fed. What else matters?'

'This other window, the one you left on the Wish ... in my world ... it wasn't the one I saw in the canal, was it?'

'No.'

'Oh. Well, if there's lots of these windows, why don't people know about them?'

'Some do. You'd be surprised. Mostly they're hidden. The one I left today I put in high orbit. Lagrange point, halfway between the Wishbone and its moon. It's collecting sunlight. This other world, Juncto ... well, they've got no sun. Not any more. Been in the dark nearly a year. They're getting desperate. I do my job, they get to see again. Like I said - things are going to pieces. This way, at least some of the cracks get patched.'

He stood for a while. 'It's amazing,' he said at last. 'I mean, you're out here risking your life. Those monsters back there - they nearly killed us. And here's you bringing light to a dying world.' He turned to me. His young face was flushed and alive. 'It's amazing. You're amazing.'

He touched my chin, tipped my face up to his. The first kiss sent a flush from my neck to my ears. The second made me cry.

'It's been a long time,' I explained when he took his lips away. I held his waist and he held mine.

'Tumbleweed,' he said, kissing me again, and again, 'does she see what we're doing?'

'She won't mind,' I said. 'She'll look after us. I don't mind. Just don't stop. Please, don't stop.'

He pushed me gently back against the soft hold wall, which yielded, embraced me. He embraced me. We moved in the fractured light of six thousand and seven secret windows.

* * *

Afterwards, he asked me my name.

'Tanager Lee,' I said. 'Folk I like call me Tan.'

'Does that include me?'

'Call me Tan.'

'All right. Tan, will you tell me something?'

'If I can.'

'The window my father went through. Do you know where it leads?'

For a long time I said nothing. Then I said, 'Yes.'

* * *

I left him sleeping, went back to the cockpit. The worlds were clicking past, over three hundred per minute. That quick, they blurred. I pinched the throttle back to five seconds per world. Why not? I was in no hurry.

When you drop, you're in freefall. It's not gravity pulling you down though. There's bigger forces at work out here, in the cracked meat of the bulk. Heavy pullers like fate and hope. Not to mention weird shit like timelash and inverse polar linearisation. You're like a fish in a pond. Everywhere there's hooks. You keep dropping, you're fine. You just got to watch where you land.

But the view . . . that's something else.

You remember King Kong? How he fell off the Empire State? Imagine what he saw on the way down. Falling past window after window, floor after floor. Now imagine each floor a ripped-open world.

There goes half a battlefield. Troops in centipede armour grappling in a fractured swamp. A whole city in flames, walls falling on the front line.

There goes a ruptured mineshaft. Diggers like ants, crushed by hydraulics, scrabbling for lost silver even as their lungs explode.

There go fields, sunset-gold, sectioned through to expose the roots of the crop, the foundations of the farms that stood before, the lost treasure troves of the firstborn settlers, the stone bones of the giants who walked this same land when it was almost young.

The drop cuts through them all. The drop's an abomination, a gash in the meat of things, too big to stitch.

But Tumbleweed's a needle, and someone's got to try.

I cranked up the throttle. Worlds get dull after a while. I looked at Jeke's ring again. The ruby shone bright, even in the dim cockpit. Really bright.

I cut the luminaires. Now there was just the volt-glow from outside. The ruby looked brighter than ever.

I shuttered the windows.

In the darkness, the ruby beamed like a beacon. Which meant it wasn't a ruby.

I crossed to the board, fired up the deep-scanner. Tumbleweed's packed with fancy kit. All the capsuli were. The brochures said they could go anywhere, hence all the tech. You land in an unknown dimension, you want to check the air before you take a breath.

Tumbleweed ran a heap of tests. She may be slow but there's parts of her smart as hell. It's just that none of the parts join up. I guess she could use some stitching too, only she doesn't want it. She's damaged goods, and she prefers it that way.

When I got the ring back, it came with a report. The report was interesting. It explained why Jeke had given me the ring.

Love was involved. Just not the way I'd figured.

* * *

'We're going back up,' said Daniel. He'd sneaked into the cockpit, crept behind me, closed his arms round my waist. I didn't resist. 'What's going on?'

'Change of plan,' I said. 'Juncto trip's postponed.'

'Why? Where are we going, Tan?'

'It's your lucky day. I'm taking you home.'

* * *

We didn't go straight there. First I got Tumbleweed to make a detour.

'There's a place you should see,' I said. I was strapped in the front chair. Daniel was behind me. He was stroking my back. My hands were busy with the helm. 'It's on the way, more or less.'

'It's to do with my father, isn't it?'

I'd figured he was sharp. But not that sharp. 'How did you guess?'

'Will I get to see him?' he said.

I didn't answer, just yanked at the helm. Tumbleweed yawed to port. A tachyon cyclone tossed us like salad. We slipped between the strings, caught the boundary wolves on the hop, were through before they could even yip. Now we were sideways-on to the broken worlds, skimming branes like manta rays, drifting further from the possible, down reality's slope towards the vale of the never.

'This looks different,' Daniel said. He kept touching me, only now I thought it was for his benefit, not mine.

'You can cut the cosmos any way you like. Comes out different every time. We're here.'

Big foils jumped from Tumbleweed's back. They spun out and up, snagged the weave of the nearest brane, held us steady. Underneath, reality did the quickstep.

'Everything's spinning,' said Daniel. He'd unbuckled himself, left the back seat, gone to the front window. I didn't stop him. 'It's like being inside a carousel. I can see ... beams of light. God-rays. Are those cliffs? It looks like they're breathing. It's like something out of Dante. If I look down I can see a gigantic whirlpool. There are rivers flowing in from every side, thousands - no, billions of them! Christ, it's making my eyes hurt.'

'There's other things than worlds in the bulk,' I said. 'This is one. What you're seeing is the Lethe. Some say it's a river, but it's really all rivers. All the waterways in all the worlds, they end up here, one way or another.'

He pressed his face to the glass. 'There are people down there, in the water. Heads and shoulders bobbing, as if an ocean liner just sank. My god, Tan, there's too many to count!'

I let him watch. I didn't join him at the window. I'd seen it all before.

'The dead,' I said. 'Lethe water makes you forget. It's one step on the way. They stay here a while, then the current moves them on.'

'Where do they go?'

'Who knows? This is as far as I ever got.'

Daniel knelt before me, took my hands in his. 'Are they here?' he said softly. 'My parents? Is this where the window brought them?'

'Most likely. We hang around, there's a chance you'll see them. It hasn't been long. Familiar faces, they got a way of turning up.'

'Will they be together?'

I closed my eyes.

I told him what he wanted to hear.

Then I asked him if he wanted to stay. He thought about it, said no, he'd seen enough. So I cranked the helm and we left.

'How did you know about this place?' he said as we climbed the steep slope back towards the shelf of the possible.

'You look hard enough, it's amazing what you stumble over.'

'Who was it you were looking for, Tan, when you first visited the Lethe?' His eyes searched mine. 'Did you love him very much?'

Like I said, the kid was sharp.

I shut my eyes again, let Tumbleweed take the helm. 'Doesn't matter. He's gone now. Buckle up. Ride'll get rocky before it gets flat.'

* * *

I cursed the kid for making me remember. Then again, why had I made the detour, if not to jog memories?

His name was Sonny. I loved him a long time before he loved me. We crewed on a clipper, back when tourists paid to see the drop. We worked long hours, shared short breaks. Gradually I won him over. When he finally saw me, he never stopped looking away.

Those days there was cash to be had. It ran through my fingers, but Sonny kept his hands cupped. Five years later he bought me Tumbleweed.

By then the cruise business was shot. Too many accidents: clippers falling between the strings, getting chased down by boundary wolves, just lost in the bulk. Folk stopped paying, stopped travelling at all. The worlds hunkered down, lost touch with their neighbours. The only trade left was shifting windows.

So that's what we did.

The adventure lasted six months. Sonny wooed the clients, I steered the ship. Each time we hit the drop we whooped and hollered. We took risks like you wouldn't believe. Everything was fireworks and fear and blood making thunder in our veins. Tumbleweed blossomed. We felt for her like we felt for each other. Sonny said she was like the daughter he never had.

I said one day I'd give him a real child.

One day turned out to be never.

We'd delivered a window to a hick world way west of the Boondocks. They were short of oxygen. Our window would let them breathe again. After, we headed back to the Wishbone - it was always our favourite stop-off. That's when Sonny saw the wolf pack.

'Look, Tan!' he said. 'Let's race them!'

I nipped him, figuring he was joking. He wasn't.

Boundary wolves prowl the torn edges of the cosmos. They scavenge, make trouble, look mean. They work mostly in packs, huge like schools of fish. On their own, they're dumb as all hell. Packed up they move fast and sure, like company gives them a brain. Only it's not the brains you worry about. It's the teeth.

A boundary wolf opens its jaws, worlds get eclipsed. Boundary wolves don't howl at the moon - they swallow it whole. You find a wolf-bite, you measure its radius in astronomical units. Easy to hide from something that big, you'd think. Think again. Their pelts are all shaggy with hidden dimensions. They mark you as prey, you get locked together somehow. Its like the windows - you and the wolf get entangled. The dimensions reel you in, and maybe the wolf shrinks, or maybe you grow, but by the time its got your head in its jaws, you're practically made to measure.

They mark you as prey, you never get free.

That day, they marked Sonny.

I did my best. Tumbleweed did hers. We clipped the low wall at the edge of time, sprayed dark matter chaff in our wake. We shot the Dreamtime Rapids so fast we woke the Rainbow Snake. We went every place we could think and more besides.

They caught us on the peak of Olympus. There was a flurry of snow and gods. Then it was all teeth. Up close, the wolves were tiny. Damn dimensions. They squirmed through Tumbleweed's seams, poured down Sonny's throat. They ate him up from the inside.

One minute he was there, next he was gone.

For a long time I wished the wolves had marked me too. But they left me alone. Don't ask me why. I don't know.

Jeke took me in. Kept me warm, kept me fed. It was Tumbleweed got me moving again though. I knew she'd be lonely, missing Sonny as much as me. So I took her out, into the drop. We roamed a long time.

Ended up over the Lethe.

We watched him go by, Tumbleweed and me. He didn't see us. If he had, he wouldn't have known us. You take the waters, everything's washed clean.

We said our goodbyes. Went back to work.

Back to riding the drop.

* * *

A mile short of the Wishbone, we hit the powder storm again. The volts struck like cobras, spitting blue fire. I let Tumbleweed steer us through the worst. She loves to feel the wind in her hair.

Hitting the brakes, I helped her over the edge. She dropped her treads, hit the mud, skidded half a mile up the runway before skewing to a stop. Mercury boiled off the outboard heatsinks. The electric scarecrow sprang erect. The scarecrow attracts volts, grounds the juice away from the hull.

I hustled Daniel through the forward conduit. He didn't ask questions. We reached the main lock. I dogged the hatch, ran the pumps. The lock spilled us into the storm.

We ran under the rain. Volts hit the mud like electric toads, eating our footprints. Ahead, the outpost loomed. The porch light was on.

The door was open.

I went first up the stairs. My hand was in my pocket, holding the box that held the ring. The box was getting hot, almost too hot to touch. When we reached the control room, something bounded across the floor. I recoiled. The creature leaped past me, almost knocked Daniel back down the stairs. He started laughing.

'Mizzy!' he cried. 'What a sight for sore eyes! How've you been, girl?'

He fussed the dog; the dog licked his face. It was touching. Me, I was watching the tall man in the shadows.

'I wasn't expecting you back so soon,' said Jeke. His voice was shaking.

'You want to correct that?' I said.

'I'm sure I don't know what you mean.'

'I mean you weren't expecting me back at all.'

Jeke stepped into the light. His face was red, tear-stained. 'It wasn't meant to be like this.'

'I know,' I said. 'I know exactly how it was meant to be.' I held up the ring. It lit the room like a laser. Burned my fingers too. I ignored that. 'Didn't think you'd see this again, did you? Where's the other one? Is that it, hanging off that chain round your neck? It's clever, Jeke, I'll give you that. Twin rings, entangled like capillary windows. Two rubies from one. Only they're not rubies, are they? They're Planck bombs. Set to arm as soon as one of the rings hits the drop. Then to detonate when it next lands on a world.'

I thrust the ring at Jeke. My fingers were blistering. 'Well, surprise surprise! This one didn't reach Juncto like you'd planned. It's back on the Wishbone instead. I guess that means the fuse just started to burn. Twelve minute fuse, Jeke. That's what Tumbleweed told me. Long enough for you to tell me what the hell you were thinking. Then, when you're done, you can disarm them both.'

Smoke was rising from Jeke's jacket. The ring round his neck, burning the skin of his chest. He ignored it, fell to his knees.

'Forgive me, Tanager,' he said. 'I know you can never love me. I just can't go on with that knowledge.' His face hardened, the tears stopped. 'Nor can I allow you to be with another.' His eyes flicked over my shoulder.

'So that's really it?' I said. 'And I thought I was flattering myself. All this ...' I brandished the sizzling ring, '... is just a fancy way of killing yourself and making sure I don't make out at your wake?'

'It's not like that,' Jeke said. 'I love you. This way we'll be together forever. The Planck value of the twinned bombs ... the long-range capillary entanglement ... when they detonate, we become entangled. Our souls. Forever.' He was sweating. 'But at short range it all falls apart. The capillary effects are negligible. We'll die together, but we'll drift apart. That's why the bombs had to be on different worlds. Tanager, don't you see? Before we could come together, we had to be apart. But by coming back here you've ruined everything!'

I crossed the room, thrust the ring into Jeke's hand. The skin of his palm turned black.

'You're a crazy man, Jeke! Stop the countdown! Get it over with!'

He closed his fist over the ring. Smoke rose through his fingers. There was a smell like a barbecue. I wondered how long we had left. Fifty yard blast radius, Tumbleweed had said.

Jeke drew back his fist and socked me on the jaw.

I dropped like a plank. I couldn't believe I hadn't seen it coming. My jaw felt like crockery. Blood pooled in the back of my throat. Then Jeke was over me, grabbing my collar, baring his teeth.

Mizzy hit him like a train. Jeke flew back against the wall, screaming curses. Daniel lifted me, carried me to the couch. Mizzy snarled and snapped, driving Jeke towards the window. His fist was still clenched. As I watched, it caught fire. The dog, smelling the flames, backed down, hackles high.

Jeke stood in the window. His hand burned like a candle. He watched Daniel cradle my head. He cried.

Then he hurled himself through the glass.

The storm poured in. Volts snapped through the broken window. Rain flooded the floor. Soon Jeke appeared, running, fifty yards out on the runway, black with the mud he'd landed in, hand ablaze. Powder-clouds rolled over him. Thunder roared.

Then the rubies exploded, and Jeke was gone.

* * *

The storm passed. Daniel patched the window, mopped the floor. I nursed my jaw, grumbled. Later, we drank chicken soup, Mizzy too.

'What will you do?' said Daniel.

I winced. The soup made my mouth hurt. 'Finish the job,' I said. 'There's folk on Juncto still waiting for the sun to come up.' I put down my mug. 'How about you?'

He stroked Mizzy's ears. 'I don't know. I don't know if I can go home.'

'It's easy,' I said. 'Back along the runway. Just keep walking. This whole area, the dimensions are thin. You'll come out near the canal. Walking on water, most like.'

'No, I mean I don't know if I want to go.'

'It's where you belong.'

'Is it?' He stood, paced the floor. 'I was thinking - if you gave this place a lick of paint, it'd be quite cosy. And I'd be, you know, here, ready for next time you're passing through.'

'Outposts get lonely.'

'I've got Mizzy.'

'Don't know when I'll next be back.'

'But you will be? Back I mean?'

'I guess.'

Later he tried to kiss me. It hurt, so I told him no. Didn't stop him. He was gentle. After a time the pain went away. Having Mizzy watch was comforting. I couldn't work out why.

'Time for me to go,' I said afterwards.

'So soon?'

'There's folk waiting. Imagine being in the dark nearly a year.'

'In some ways I think I have.'

I fussed Mizzy. She licked me. I was glad he had her for company.

'Before you go,' he said, 'tell me something.'

'What?'

'Why do you call it the Wishbone?'

I started down the stairs, stopped, said, 'Remember what I said? How every world's a bone? Some bones ... they're more fragile than others. Special. You pull them too hard, they break. They need a special touch. Need looking after.' I tapped the outpost wall. 'Do it up nice. See you next time.'

* * *

Back in the cockpit, I ran Tumbleweed's pre-drop checks. I knew she'd missed me, so I didn't rush her. Once she was set, I eased her up to the edge. The storm was over and the view was clear. The drop looked almost inviting.

I closed the cockpit and opened a line to the Wishbone Outpost.

'You there?' I said.

'Is this the right button?' said Daniel's voice through the speaker.

'I hear you, so I guess it must be. You got a forecast for me?'

'Uh, I don't know about that. There's a lot here to learn. But from what I can see through the window, everything looks clear and fine.'

'Clear and fine. Sounds good. Dropship out.'

I fired up the board, held my breath. Eased her over the edge.

Together we rode into the drop, Tumbleweed and me.