"That is the most perverse use of the law that I have ever heard of," Samuel Krapp exclaimed.

Thomas Price Riddle closed the law textbook he had been balancing on his lap and looked at his "student body." If a man could call it that. A dozen young men and women. At first, the only students who had come to him had been girls, like Laurie Koudsi and his granddaughter Mary Kat. And Ricky McCabe, with the police force. Most of the young men had already been called into the army, or busy on technical projects, before it had occurred to anyone in town that they might, possibly, if they survived, need a few more lawyers. Then the government of the New United States—now the State of Thuringia-Franconia—had thought that some of its civil servants and bureaucrats could benefit from an introduction to legal principles. So he had added a few up-time young men who came when they could and, if they survived their postings elsewhere, would come back if they could. Those were doing most of their course work by mail.

The new lawyers, "baby lawyers," like Laurie and Mary Kat still came to class. He hadn't managed to cover everything when he pushed them through his first version of a law course. Luckily, they knew it. If they hadn't known it when they passed the bar exam he and his son Chuck designed, they had found out during their first year or so of active practice.

A couple of years later, even the military had recalled that there was only one person in town who had any experience with administering the Uniform Code of Military Justice, and that person was not precisely youthful. His "student body" had increased in size to include young officers taking law courses in what counted as their spare time.

Now he had a few down-timers as well, some students from the University of Jena putting in a semester in Grantville, but mostly associates from the German law firms that had opened branches in town—men who already had their degrees and, in most cases, a few years of practice, but who realized the need to build bridges between the up-time and down-time codes. Or like young Samuel Krapp, a cousin of the friend and rival his granddaughter Mary Kat addressed as "Georgie," who had just finished law school in Jena last year and was adding the practice of up-time law to his licentiate before starting graduate work in pursuit of the Dr. utriusque jur.—an advanced degree that would allow him to rise to a professorship or judgeship someday.

So he looked at Sam. "What I just explained to you is far, far, from the most perverse use of the law that I ever encountered in my practice. And, probably, far from the most perverse that you may encounter in yours. There is a reason for the quotation, 'The law, sir, is an ass.' Maybe," Riddle said, "the time has come that I should talk about something other than the law in the strictest sense of the word." He placed the textbook on the lamp table next to the arm of the sofa. "Let me tell you a story. Speaking of my Uncle Abner . . ."

He closed his eyes. "Abner Patton was actually my uncle by marriage." He smiled at Sam. "He was married to my mother's sister—Ann Price was her maiden name. Aunt Ann. I think that I prefer the down-time terminology for these things. When you bring me a document on probate that refers to Mutterschwestersmann or Vaterschwestersmann, I know that it's an in-law who is probably involved in the case as an adult male who has potential to serve as an executor or a guardian—not a blood relative uncle with possible inheritance claims. Muttersbruder tells me directly that a specific 'uncle' has concern for the child of a marriage, but no claim to the farm in which the child's late father held a quarter-share. That can be very useful data." He ran his fingers through his thin white hair. "But perhaps I am digressing from the point."

Not one of the students shifted with impatience. They had learned, some more quickly than others, that even when Tom Riddle appeared to digress from the topic, there was usually a connection—if they waited long enough, without interrupting his train of thought.

Johann Georg Hardegg, seated next to his cousin, wondered idly why it was a "train" of thought in English rather than a "chain" of thought. True, railroad cars were coupled together with hitches, but the links of a chain were fastened even more firmly.

"Abner Patton was a foreman at the ceramic plumbing fixtures factory. My father, Theodore Riddle, was a manager there. Pa was born in 1898—Spanish American War, that year—and named for Theodore Roosevelt. Though nobody ever called him Teddy, as far as I recall. Abner was a few years younger than Pa. But the man his name reminded me of was older than TR. And only lived in the pages of magazines and books."

Riddle turned his head, looking at the bookshelves on the wall behind the sofa. He grasped his walker and started to pull himself up.

Mary Kat jumped first. "What do you want, Grandpa?"

"Um. To the left of the fireplace. Second shelf, I think, about a foot in from the left side. A black-and-gray dust jacket with a small tear at the bottom. Melville Davisson Post. The Complete Uncle Abner."

The book was right where he said it would be.

Riddle took it and flipped it open, without even bothering to glance at the table of contents. "Post's 'Uncle Abner' stories are set in West Virginia—one of the reasons I like them, but not the main one—in the years before the Civil War. Back before the state seceded from Virginia, so, I suppose, they were really set in a remote region of Virginia, if one feels impelled to be precise. Which a lawyer should. Always. Naturally.

"Now, Post's Uncle Abner was a defender of the innocent." He looked at Sam Krapp. "You might want to read it. You can borrow the book after class tonight."

He closed his eyes. "The story I was thinking about, 'The Strange Schemes of Randolph Mason,' isn't in here, though, because it wasn't an 'Uncle Abner' story. It came out in a magazine. I don't think I have a copy of it here. Well, I might have photocopies of the Randolph Mason stories in one of my filing cabinets, but it would take a lot of looking to dig them out.

"Post's father was a lawyer. So was Post, himself. I suppose that might be relevant. Randolph Mason is a lawyer. A smart lawyer and a perverse lawyer. A cynical lawyer. One who uses his skills and undoubted mastery of the legal system to set criminals—genuine criminals, embezzlers, thieves, a crooked sheriff who abused the power of his office; not the unjustly accused—free. And considers himself to be a defender of the weak and powerless all the while he does it. I sure wish I could find that series of stories."

Hardegg looked up. "Why? What do they show that is important, specifically?"

"What were we just talking about, Georg?" Riddle smiled. "Before young Sam became morally indignant and I went off on this tangent, that is?"

"You were discussing 'legal technicalities,' and the abilities of lawyers to get men off in American courts under the up-time law by using procedural improprieties, such as lacunae in the chain of custody for evidence or . . ."

"Improper police procedure," Krapp interrupted, receiving a cousinly glare for his trouble.

"Precisely. Thank you, both of you. However, in Post's stories, Mason did not use this approach. Rather he had the defendants admit precisely what they had done—that they had in fact committed the acts of which they were accused. These acts were—necessarily, if the stories were to succeed as literary devices—not common or ordinary crimes such as assault, but devious and, well, extraordinary. Mason would then proceed to demonstrate to the court that the laws, as they stood on the books, simply did not cover the action committed by the defendant and could not be stretched to cover the action committed by the defendant. Mason's point was always that while his client freely admitted that he had done something manifestly unfair, unjust, and morally wrong, it was nonetheless not illegal and did not fall within the purview of the current statutes."

Hardegg nodded. "He, then, undertook, ah, adventures, or explorations, perhaps . . ." He shook his head. "I am not sure of the precisely correct word in English. But . . . this practitioner applied the pure logic of the law. As legal scholars are accustomed to do, often to the point of absurdity. But Mason used logic to display the law's shortcomings. It's inadequacies. Thus the stories would have been designed to show—as in last summer's unfortunate matrimonial tangle of Patricia Fitzgerald—the inability of human reason to predict, and thus to cover within the pages of a legal textbook, all of the things that human beings may do."

"Especially all of the deep troubles from which Randolph Mason specialized in extricating his clients," Riddle said. "Long before the techniques of television's 'cop shows' of the later twentieth century, Post's Mason, in the story called 'The Corpus Delicti,' spent much time on such topics as the legal difficulty of prosecuting murder charges in the absence of a corpse—and the then-modern advances in scientific knowledge, at the turn of the nineteenth into the twentieth century, that contributed so helpfully when a miscreant found himself in need of making a corpse disappear."

Sam Krapp nodded. "Possibly, then, being of relevance when our theologians question whether all of the advanced technology that the up-timers urge us to adopt, so very strongly urge us to adopt, is really beneficial."

Mary Kat cocked her head sideways. "That too, though . . ." She had been introduced to the literary Uncle Abner long before, when she was in high school. "Post showed good things about the use of physical evidence, too. Horse tracks. Things like that. Even if he didn't always explain to the reader exactly what it was that Abner was seeing when he looked at a crime scene. That's not considered exactly fair in the classical detective story."

"Possibly both of you are correct," Tom Riddle said. "Even probably, both of you are correct, more or less to the extent that each of the six blind men observing the elephant was correct, given that his other writings—" He held up The Complete Uncle Abner again. "—are full of exposition on religion. Perhaps the best known of all of Post's stories—" He nodded toward the book in his hand. "—has the title 'Naboth's Vineyard.' He certainly expected his readers to grasp the reference. Philosophy and morality, also, but certainly religion. And democracy and the meaning of democracy in practice."

His eyes becoming shrewd, he looked at his students again. "Which of you, if called upon, would feel prepared to summarize the underlying moral of 'Naboth's Vineyard' for me without first going to look up the phrase?"

All of the down-timers raised their hands. Of the up-timers, only two of the seven.

Riddle muttered something about rampant cultural illiteracy. Nodding at the five, he said, "Be prepared to summarize it and explain the point of the passage, in the legal context of the historical period in which it occurred, by Thursday. If you manage to figure out where to find it, that is."

They looked back at him, expressions blank.

"Since we are discussing detective stories, perhaps I should give you a clue. Another of the 'Uncle Abner' stories, which revolves almost entirely about matters of the law and various types of legal swindles, has the title, 'The Tenth Commandment.' If my wife Veleda is feeling charitable, she may be willing to introduce you to the existence of a type of reference book usually called a 'concordance.'"

Mary Kat looked down, hiding a smile. Her grandfather was rarely acerbic. Even when he was, he did not follow the model of the law professor in Paper Chase, the icon of up-time law students for decades. That his sarcasm was presented gently did not make it any less acid, if a person knew what she was hearing. Grandpa knew perfectly well that Grandma would leap at the chance to introduce anybody at all to the use of a concordance, with a few well-chosen sentences about the need for one.

"Not just detective stories, although the puzzles are fascinating. Democracy," Tom Riddle said. "And the place of the law within a democracy."

He looked at Samuel Krapp. "So read it, young man. And when you're done . . ." He looked at five children of Grantville who could not identify Naboth's vineyard. "The rest of you read it, too. Take notes. Annotate your notes. With special reference to ambiguities."

Mary Kat raised her eyebrows.

"Think, child," her grandfather said. "What position does Uncle Abner hold in his community? Is he a policeman?"

"No."

"An officer of the court? A judge?"

She shook her head in the negative.

"Who is the righteous and honorable justice of the peace whose efforts Uncle Abner assists in righting wrongs and administering justice?"

Mary Kat opened her mouth; then closed it; opened it again. "Squire . . . Randolph."

"The two sides of the law in society. Always, the two sides of the law in society. Do not forget them." He handed the book to Samuel Krapp as the door to the living room opened. "And, now, I believe that Veleda has prepared some refreshments."

"Professor Arumaeus has published really a lot of books," was the way that Georgie Hardegg put it to Mary Kat, "which in due time led to his becoming dean of the Faculty of Law at the University of Jena."

She nodded. "Publish or perish; a well-known principle in academic careers."

"His major area of interest is public law, but he wrote one rather interesting diversion on the topic of the legal definition of stipends, mercantile income, and wages, which has led to any number of academic disputations on the topic of whether or not such social groups as entertainers, fortune tellers, gypsies, and faith healers can truly, from a philosophical perspective, be said to earn income."

"Oh."

"He's not bad at public relations, either," Hardegg summed up.

"You might as well come with us," Sam Krapp said. "You're going to have to meet him some day—you and Laurie Koudsi both—if you intend to do anything with your law practices beyond the limits of West Virginia County. You'll need to get your regular licentiates; not just the 'bar exam' that your people invented after the Ring of Fire.

"Is my German really good enough to get through a meeting with a dean? Much less my Latin?"

"His English is fine if it comes to a pinch," Hardegg said absently. "He studied at Oxford before he got his doctorate. Anyway, he's curious to meet you, given that the dean of the Faculty of Arts has hired the famous Ms. Mailey to teach up-time political science. Which is quite a coup, since she's possibly the only person in the world today qualified to teach the subject. The best-qualified, at least. Or the most famous, anyhow. It should bring in a lot of students, which, of course, means a lot of income and prestige for Jena."

"Well, Jena had an advantage in the bidding wars, considering that Dr. Nichols is already on the medical school faculty there. I sort of doubt that, once she got out of England, Ms. Mailey was interested in taking a job outside of his sphere of influence. If she travels any more, she says, it's going to be with him, like the Prague trip. She didn't even wait in the Netherlands for the wedding—just came on home. I was honestly surprised, though, that they hired a woman."

"Who else could they hire?" Hardegg asked. "It's not as if she had any competition for the job. It's sort of like a ruler sending his sister or daughter as a negotiator instead of some faceless bureaucrat." He thought a moment, then grinned. "The bureaucrat, as a noble male of the human species, can always save what face he does have by thinking that if the ruler had a brother or son available, he'd have priority over the females in the family."

"Ms. Mailey is coming in as an extraordinary professor," Krapp pointed out. "If they'd hired her instead of a down-time academic with all the proper degrees as an ordinary professor, the faculty members would have made a lot more fuss, I'm sure."

"I get it," Mary Kat said suddenly. "She's an 'in addition to' rather than an 'instead of.' Or 'untenured adjunct' rather than 'tenured regular' professor."

"The university is paying her more than they pay most of the ordinary professors, though. They really do expect her to be an attraction." Hardegg turned to Krapp. "Who's doing the Latin translations for her handouts?"

"Cunz Kastenmayer. At least, I think I heard someone say so. Because of the Dreeson tour this fall, he has a sort of 'in' with the up-timers now."

"Odd sort of guy. But he does make the most of his chances. For someone who's never had a chance to make the grand tour, he's compensated by making friends with every single foreign student who shows up in Jena and talking to him in whatever his native language is. Somebody ought to fix him up with a plummy tutoring job, so he can travel around with some rich kid."

* * *

Mary Kat just listened almost all the way to Jena. That was one thing she had learned. She could often find out a lot more about what was going on in the down-timer community by listening to her colleagues talk to one another than by talking with any of them herself.

Until, near the end of the trip, she asked, "If you find the premises of Post's stories, the 'crucial' ones that you've hand-copied and we're taking for him to look at, to be so very 'Calvinist,' aren't you worried that this Professor Arumaeus will be offended by them? It's a Lutheran university, after all."

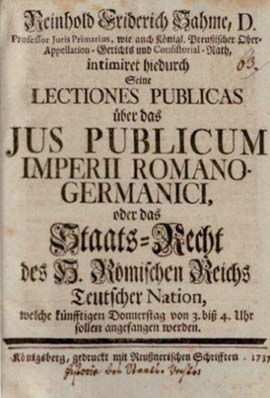

"The university is Lutheran," Hardegg agreed. "So the professors have to be Lutheran, of course. But Arumaeus isn't. Or, at least, he wasn't. He was born in Leeuwarden in the Netherlands. Dominik van Arum, Latinized into Domenicus Arumaeus. He was a Calvinist until he took a job at Jena—that must be close to thirty years ago, now. He's the one who introduced Staatsrecht, the law governing such things as sovereignty, as an independent subdiscipline here."

"Well, all of them are," Krapp said. "Almost all, at least. Althusius, for example. The professors at Herborn and Leiden. And Hoen."

"All what?"

"The scholars and professors with a serious interest in public law. Constitutional law, perhaps, would be a better term in English, except that it can be confusing, since no political entity in Europe has a constitution in the sense of your American written constitution."

Hardegg nodded. "Ever since Lipsius. Maybe because of Lipsius—his Politica is still very influential, nearly thirty years after his death. The people who are developing the theory of the law of government. Men like Arumaeus. And Grotius. A lot of them, as Sam says, are Calvinists from the Netherlands. Though I have to say that the Jesuits are also publishing on the topic. If Ms. Mailey were going to teach down-time political theory, she would have had plenty of competition. I wouldn't be surprised if the university hires a down-timer, now, in the Arts Faculty, to complement her courses. At present the field is taught only in the Faculty of Law, except in so far as it can be addressed in rhetoric courses through the Greek and Latin classics. That would bring in even more tuition-paying students."

"I have news for you," Mary Kat said.

"What?"

"If they think that Ms. Mailey is going to turn into a Lutheran because they hired her, they'd better think again."

"Ms. Unruh is Lutheran," Krapp said. "The extraordinary professor for statistics. I know—I've seen her in church in Jena on weekends she doesn't return to Grantville."

"That's different. She was Lutheran already. She's a member at St. Martin's in the Fields."

"What about Ms. McDonald in the medical faculty?"

Mary Kat frowned. "Presbyterian, I think. Most of the McDonalds are. And Mary Pat Flanagan is Catholic. Maybe they're making exception for the adjuncts."

Krapp frowned. "Lipsius taught for a while at Jena, too—ethics, logic, and history, in the Faculty of Arts. He never became a Lutheran, so maybe they are. Have. Do. Make exceptions, I mean."

Hardegg shook his head. "No, he was a Catholic from the Spanish Netherlands and had to convert to Lutheranism to be hired. The faculty was skeptical of his sincerity. That's why he had to leave again after only two years and go to Cologne. I've heard people talking about it. He only became a Calvinist, later, when the University of Leiden hired him. They say that's why he eventually applied for the job at Louvain—so he could go back to being Catholic. Though he was really a Stoic all along, no matter which confession he belonged to at the moment."

"I read the book," Mary Kat said. "All six sections. Grandpa said I had to. He ordered the English translation from a used book store here in Jena, because my Latin wasn't up to it the first couple of years after the Ring of Fire. The title page is burned upon my brain. Justus Lipsius, Sixe Bookes of Politickes or Civil Doctrine, Done into English by William Jones (London: Richard Field, 1594). I didn't like it at all and didn't agree with a word of it."

Krapp laughed. "I never expected that you would. Anything that Richelieu likes, anything that Maximilian of Bavaria admires, anything that Count-Duke Olivares considers a model of statesmanship . . ."

"Just doesn't do it for an old hillbilly girl. 'You have a choice between a virtuous authoritarian prince or anarchy and civil chaos.' That about sums it up for Justus Lipsius. No faith at all in ordinary people and their ability to govern themselves. As if we don't have any more sense of justice than a herd of pigs. Talk about a proto-Hobbes!"

"You'll probably like Arumaeus' ideas better, if you read his book. It's actually an anthology that he edited: Discursus academici de jure publico. It came out in five volumes several years ago, but I think it's still in print. As far as the Holy Roman Empire is concerned, he's pretty much in favor of the rights of the individual territories. Federalism, I suppose, except that it's not exactly the same thing the up-timers define as federalism."

* * *

"My daughter wanted to meet you," Dean Arumaeus said, thus explaining the presence of a severely dressed young woman in her mid-twenties in the room. "She feels somewhat deprived because she is only the daughter and wife of lawyers, without being one herself."

Mary Kat suspected that he was repeating a joke he had made many times before.

His daughter's face—her name was Dorothea Susanne and her husband, Ortholphus Fomann, was also present—indicated that it was a joke she was tired of.

Very tired of.

She'd clearly heard it much too often.

"Ortholphus' father was born in Schleusingen," Arumaeus continued. "He was a prominent member of the law faculty here at Jena until ill health forced him to retire; I'm sad to say that he died earlier this year. His mother is still alive—one of Georg Mylius' daughters."

He clearly expected Mary Kat to be impressed by his son-in-law's genealogy. She made a mental note to find out who Georg Mylius was. Or had been, since the implication was that he also was deceased.

* * *

"While you are in town," Professor Arumaeus said, "your escorts really should introduce you to Professor Ungepauer. And to Johannes Limnaeus, since he is in town with Margrave Christian of Bayreuth. Both of them are already acquainted with your father, Chief Justice Riddle, of course." He picked up the "crucial stories" from The Complete Uncle Abner that Hardegg and Krapp had copied for him. It was a dismissal—a polite one, but clearly a dismissal.

The dean was imposing, Mary Kat thought. Not just heavy, though he was, um, somewhat overweight. Also impressive and certainly an effective speaker. It was scarcely surprising that the former dukes of Saxe-Weimar had used him as a diplomat in addition to his other duties. He could probably talk a hen into laying her egg right into his hand.

* * *

His daughter escorted them to the door, where she stopped and looked at Hardegg and Krapp, nodding toward the steps.

Sam grabbed Georgie's arm and pulled him outside.

"What?"

"I just thought. Margrave Christian of Bayreuth. Cunz Kastenmayer. He's got two sons—the margrave, not Limnaeus. Rich kids, really rich kids, and just the age to be starting on a grand tour. Run and find Cunz—he's bound to be in the library. Get him here while we have an absolute order to go introduce Mary Kat to his most important councillor. SoTF Chief Justice's daughter. Mayor Dreeson's tour. Recommendations. We've got to take Cunz along when we talk to Limnaeus."

* * *

Mary Kat stayed where she was.

"I am tired of the joke," the young woman said. "I was sixteen when my father decided I should marry. Ortholphus' first wife had just died—she was Professor Hilliger's widow. She left him with a stepdaughter and daughter to care for, both under five years old, so he needed another wife right away. He was also a law professor at Jena—Oswald Hilliger, that is. I do not resent the marriage; I love my daughters—those two and my own. She is three, now. But I am tired of the joke. So tired of the . . ."

"Condescension," Mary Kat suggested.

"That will do."

"What do you need from me?"

"Give me your grandfather's address, please. I have lived among jurists all my life and I am not stupid. My mother's father was a law professor here at Jena, too—it's not as if I've never seen a law book in my life. I've done more than just dust them like a good little Hausfrau. I want information on what more I need to learn, specifically, to take this 'bar exam' that exists in West Virginia County." Dorothea Susanne smiled. "I couldn't practice, there, of course—not living in Jena. It wouldn't be practical. But perhaps, if I pass an examination that proves I know these things, he will stop it."

* * *

"You'll probably find Limnaeus' work on the constitution of the Holy Roman Empire of even more use than the one Arumaeus compiled," Sam said on the way home. "It's more systematic. Ius publicum imperii romano-germanici. Only three volumes, too. They came out in Strassburg between 1629 and 1632, so you won't have to bother with the used book trade—you can just order them from the publisher."

Mary Kat sighed. "I don't suppose there's an English translation. How can you possibly be so enthusiastic about three more volumes of Latin?"

"Well, I do want to become a law professor." Sam grinned. "Some day, I'll make a great reputation for myself by writing a definitive treatise on comparative up-time and down-time constitutions. If you ask the professors right now, 'Who are the upcoming lights of the legal profession?' they'll name Conring and von Chemnitz, or the younger Carpzov over in Saxony. They're all five or six years older than I am, though. Just wait."

Hardegg laughed. "Whatever else you may lack for, Samuel, it is not self-confidence."

"Just wait," Sam said. "Just you wait."

"Well," Tom Riddle asked the class the next week. "What do you know about Naboth's Vineyard."

"I looked it up," was the offering of Jon Villareal, back from Würzburg at Wes Jenkins' behest to take over duties as deputy director of the SoTF Consular Service—a job reputed to require some minimal legal knowledge—offered cheerfully.

"What did you find?"

"Jezebel." He hummed a couple of musical phrases.

"That's all?"

"Hey, Mr. Riddle, I hardly had time for deep analysis this week. The new boss will be arriving any day now and we have to get the office up and running the way he wants it."

"That is the story of this seminar, I sometimes think. At least we are testing all of you on the basis of what you have learned by the end, rather than on how fast you learn it. Anyone else?" He looked at the other four culprits who had professed themselves to be ignorant of the existence of Naboth's vineyard.

"Elijah came along and made a prophecy that the dogs would lick up Ahab's blood," Paige Clinter contributed.

"True enough. Why?"

"Because Ahab coveted the vineyard and that's against one of the Ten Commandments?" Catrina Dion Kennedy suggested a little dubiously.

Lawrence Quinn, who had only recently joined the seminar, shook his head. "That's only part of it." Then he looked a little anxiously at Riddle and added, "I think."

"Go ahead."

"Well, I was talking to Babette about it when Joe was down from Erfurt this week." He waved at Babette Salerno, who was married to one of the Goss brothers. "Joe sat in on our study group and said that what connected it to the story was that the king and queen, who were supposed to use their authority for the good of the people they ruled, instead used it for their own advantage. And that Jezebel ordered it, but Ahab was just as guilty, because he took advantage of what she did. And the officials and leading citizens were guilty because they obeyed Jezebel's order. Even if the queen tells you to do something, if it's an illegal order, you aren't supposed to obey it."

Riddle heaved a dramatic sigh. "A potentially great legal mind, lost forever to the cause of improved radio communications, I fear."

Babette giggled.

Samuel Krapp shook his head. "It's what the passage is about—1 Kings 21. But it isn't what Melville Davisson Post's story is about. You're all a little right, but you're all also a little wrong."

"Like the six blind men and the elephant?" Mary Kat asked.

The seminar digressed once more, the digression ending only when she promised to make enough copies of the poem to distribute to everyone the next week.

Riddle nodded to Sam again.

"The parallel that links the two is the person in authority who covets something owned by another. But the story, Post's real story, is about where sovereignty resides under a republican constitution. For which insight I thank Mary Kat."

"But . . . I hadn't figured that out myself. I didn't ever say anything of the sort," she protested.

"You didn't have to," Georgie Hardegg said. "It became perfectly clear to both of us the moment you explained exactly why you hated reading Lipsius so much."

"You can't get through everything in those filing cabinets in one day," Veleda Riddle protested.

"I'm not going to do it by myself, Grandma. Catrina Dion and Babette are coming, too. We'll each take one cabinet today; start on the top drawer and work down. Make an inventory of everything Grandpa has. Finding the rest of the stories by Melville Davisson Post that he maybe did and maybe didn't photocopy once upon a time will just be a side benefit. Who knows how much more useful stuff he has stashed away in there. Nobody's ever had time to look. We'll make duplicate cards, one set for you to keep here on top of the cabinets and the other one for the state library. Elaine Bolender gave us a supply of their cards and I dug a hole punch out of Mom's desk. Babette and I can sprawl on the floor, but Catrina Dion needs a chair with a pretty high seat. At seven months along, she can hardly heave herself up once she's down. I predict the kid's going to be as big as Brendan Murphy."

"Do your friends really want to give up their Sunday afternoon? Afternoons, if you don't finish today. I don't think you will."

"We're the three musketeers. We stick together. All for one and one for all. Babette sees more of Joe than I do of Derek or Catrina Dion does of Brendan. The honest truth is, though, we'd all be as lonely as sin if we didn't have each other."

Her grandmother nodded. "I had friends like that, back when Tom was in the military." Then, tentatively, "How is Catrina Dion doing right now? Because of her father, you know."

"The skunk. The absolute, utter skunk. Defecting to Austria for money. The Masaniellos are just . . . livid."

"I can imagine."

"Her mom's divorcing him. Even though they're Catholic. She filed this week."

"That didn't take long."

"Tim Kennedy's not going to be any skunkier next month than this month. She'll stay here in Grantville until the divorce goes through—Lisa Masaniello, that is, Catrina Dion's mom. After that's over, the Leeks have asked her to come up to Magdeburg and join the staff of the Magdeburg Memorial Hospital that they're funding. Since Brendan's already up there, and plans to stay—which I would, too, if I was Keenan Murphy's cousin—I expect that Catrina Dion will go, too. Not till next summer, though. She'll wait till her mother's ready and the baby's a bit older.

"Today, though, we're indexing Grandpa's filing cabinets."

Veleda nodded. "Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof. Matthew 6:34. I'll see to the refreshments."

* * *

"The ideas of Philipp Heinrich Hoen—he works for the counts of Nassau-Dillenburg and Nassau-Dietz, who are relatives of Stadholder Frederik Henrik in the Netherlands—in regard to federalism, especially since . . ." Sam interrupted.

Tom Riddle frowned at him. "In due course, young man."

Krapp subsided.

"Now. As I was saying in regard to the development of the covenant tradition in law, as it pertains to the relationship between the government and the governed . . ."

* * *

"Ah," Arumaeus said appreciatively. "My dear Mrs. Riddle. The hot chocolate was delicious. The berry tortes are superb. The whipped cream . . ."

Veleda beamed with pleasure. Nobody else in the world was going to equal her whipped cream in her lifetime, she was sure. At the time of the Ring of Fire, she had five pounds of confectioners' sugar in the second freezer, the one in the basement. A pound had come out for Marty's wedding, a pound for Chuck's appointment as chief justice, a pound for Mary Kat's wedding. She was glad she hadn't broken into it when Marty's children were christened—she thought something more important was likely to happen—and if nothing else, she would save it until the children themselves were able to enjoy a taste.

For this occasion, however, she had doled out a few ounces.

"In return for your generous hospitality and your husband's agreement to loan me this book, The Complete Uncle Abner, with permission to have it reprinted with distribution to every law faculty on the continent, and at no cost—is there any favor that I could possibly perform for you?"

She smiled beatifically. "I understand that many foreign students come to the university of Jena.'

"Yes."

"If you should identify one who is already ordained as a clergyman in the Church of England—would you ask him to visit us in Grantville, please? My prior efforts to acquire a minister for the church we are reopening . . . I will not say that the tree has definitely proved to be barren, but it has not yet produced a ripe fruit."

"Why, of course. I should be delighted. I will have my colleague Ungepauer notify the registrar to be alert the minute I get home."

"Would you care for another piece of torte? There's still some whipped cream left."

Arumaeus beamed. "How kind of you, Mrs. Riddle. Why, yes."

Mary Kat started jumping up and down in front of the store window. "There it is. It's perfect. Perfect, I tell you. Here I've been stewing about what I was going to get him for Christmas and there it is, right in front of me. Perfect."

Babette laughed. "You're not even a little bit excited that you're going to see Derek again, are you?"

Mary Kat glared. "No, of course not. How many jackpots can a girl expect to hit in a lifetime, after all? I got nearly six feet of guy with curly rust-red hair, hazel eyes, lots of freckles, and an infectious sense of humor—and he's smart, too. No, I think I'll just wander around being blasé about the whole thing. Like hell I will—I never dreamed that any marriage of mine could actually be fun until I met him and I'm not going to miss a minute of it."

"You didn't expect marriage to be fun?" Catrina Dion frowned.

"Well—maybe it's just that my parents sure don't seem to have any fun being married to each other. It's not that they aren't fond of each other, I think. I'm sure they're both a hundred percent faithful and loyal. But they never laugh with each other or tease one another the way Grandpa and Grandma still do. And I've sure never caught them sneaking a kiss on the sly the way Grandma and Grandpa still do."

"They do?" Babette asked, a blank expression on her face. This was a new insight on the life of her law professor. Who had to be eighty years old, at least.

"Oh, they sure do. As for Mom and Dad, sometimes I just think that a time came when they were the right age to get married, and each of them was the kind of person that the other one expected to marry, so they did and then just made their minds up that they'd enlisted for the duration."

"That's sad."

"Maybe they did enjoy one another at first. There are some snapshots in Grandma's album right after they were married when they didn't look so dutiful. Maybe parenthood took it out of them. Marty and I've talked about it sometimes. He's three years older than I am, but he doesn't remember either that they ever had fun together. That would be sad—if having us come along made them feel so . . . responsible . . . that nothing else was left. Having to set what they considered to be a good example absolutely all the time. Things like that."

Mary Kat reached for the handle on the door. "Just let me go in and buy this before somebody else snatches it out from under my nose. Then we can go to Sternbock's and grab a cup of coffee."

* * *

"No coffee for me, Theo," Catrina Dion said. "I'm going down to the train station to wait until Brendan gets in and they don't have a bathroom. What with Junior here . . ." She looked at her stomach. "Well, anyway, no coffee. Thanks, but no thanks."

"Coffee for both the other lovely ladies, though?"

The other two lovely ladies agreed.

"Brendan's here for how long?"

"He's staying for a week or until after the baby shows up. If the baby shows up sooner, for a week. If not, longer. He wangled something with his supervisor. What's your schedule, Babette?"

"Up to Erfurt two days before Christmas, and staying until after New Year's."

"And Derek will be here just any day now, depending on the roads from Fulda. So." Catrina Dion raised an imaginary toast. "Happy holidays to one and all." She shifted in her seat and knocked over Mary Kat's tote bag full of packages. "Damn, I'm sorry. Where did you meet Derek, anyway? He didn't go to high school here, did he?"

Mary Kat shook her head. "He's from Fairmont. The brother of Lisa Dailey, at the high school. He grew up in Fairmont, went to college in Fairmont, worked for the county parks department there, he and Rhonda had Hannah Rose there. Except for when he was in the army—that's when he met Rhonda and married her—he was a Fairmont boy all his life. He was over here to go to the sports shop, to listen to Allan Dailey debate with himself about some new fishing gear, the afternoon of the Ring of Fire and lost all that. Everything. All at once. So he joined the army right away. Like the next day after the Emergency Committee called for volunteers. April 2000 or May 1631, depending on how you look at it, and just buried himself in it. I didn't run into him until the fall of 1632—late fall, just a couple of weeks before Stearns and Jackson sent him over to Fulda to be the NUS military administrator there. Well, really, Wes Jenkins picked him for his team—they knew one another through the Marion County Parks Department, back before. That's why he was at the diplomatic party at all—Wes and Scott Blackwell made him go."

"You ran into him where?"

"At a blasted social event. You know the kind. It involved Dad and the NUS supreme court on the one hand—a big meeting about how the new court was going to interact with the existing Schöppenstuhl and Saxe-Weimar Hofgericht in Jena. And all the administrators who were being sent to Franconia—I suppose Ed Piazza decided to spare the budget by having two receptions in one. It was in the big hall at the middle school—which is actually pretty impressive architecture, when you go back and look at it as an adult. Mom said I had to go. Formal." She leaned back. "I am just not the formal-wearing type."

"You had a formal?" Babette asked with some disbelief.

"I had a bridesmaid's dress. For my college roommate's wedding. Undergraduate roommate—she got married my first year in law school." She grimaced at them. "A sort of bright pink with blue undertones, butterfly sleeves, a little back bustle with a bow on it, taffeta, and just to make the general effect worse, cocktail length with a crinoline under the skirt."

"Oh," Babette said. "Oh, no."

"So I was standing there, feeling miserable and looking as wretched as I'd ever looked in my life except at the wedding when I wore that same stupid dress, when this guy standing behind me laughed at something. I turned around. He crinkled up his eyes and said, 'I'm not Ogden Nash, but I'll write a poem for you.

Let me guess.

Bridesmaid's dress."

"I could have spit. Here was a guy, a real, live, nice-looking human male somewhere near my age. Apparently unattached, which was as rare as hen's teeth in Grantville that winter. A man who didn't go to school with me and therefore wasn't likely to know that Voss Gordon gifted me with the nickname 'Stumpy Widebottom' when we were in seventh grade and it stuck all the way through high school. I was looking so bad that I figured I might as well make a defensive play, so I said, 'I know, I look like a lampshade in a brothel.'"

"And?"

"He laughed again and said, 'I'm not personally familiar with brothel decor, but I think the effect is closer to a peony in full bloom. Except that with the legs sticking down, the poor blossom has two stems instead of one.' Then we talked some—" Mary Kat started acting out the dialogue with two speakers.

"'You should have seen the bridesmaids' dresses at my sister Lisa's wedding.'

"'They couldn't have been worse.'

"'They could have been. They were. Someone told me the color's called chartreuse, but it looked like . . .'

"'Never mind. I know.'

"'Would you like to dance?'

"So we danced. And saw one another for two weeks. Then he went off to Fulda; we wrote letters until February 1634, when he came back and we got married as soon as we could get a license. Mary Ellen Jones did the honors in the parlor of the Methodist rectory, much to Grandma's disgust. She really wants to get an Episcopalian minister into this town."

"Now that we know about. We were there, after all. The straight skirt and cable-knit turtleneck sweater in winter white looked really good on you. And Doria managed to miss out on having to get a bridesmaid's dress, considering that she was eight and a half months pregnant."

"I'd have loved to have both of you stand up with me, too. But all Derek's friends were in the army. It was hard enough to pry Allan Dailey loose to be the best man and one of the witnesses, without trying for two more. Marty had to hold Chuckie—he was going through a stage where no one but his parents would do at all. Anyway, if my brother had been a groomsman, then I'd have had to ask Lisa to be a bridesmaid, and we'd still have been short two men."

"We were happy to be guests, honestly. Don't worry about it. It was a very nice wedding," Babette said. "Followed by the famous three-day honeymoon, during which the two of you never emerged from your suite at the Higgins Hotel."

"We knew he had to go right back, what with the Franconian election on tap and the Ram Rebellion heating up. Why waste any of our time by traveling? They have room service."

"You just collapsed," Erasmus Ungepauer said to Domenicus Arumaeus. "With no warning at all. Right in the middle of a faculty meeting."

"Which is why I am in the hospital rather than in my office?" Arumaeus looked from his fellow professor to his wife.

"The law school should count itself lucky that it was all-faculty rather than just jurists. There were enough medical types there to get your heart going again in a hurry." Anna Pinzingerin verh. Arumaea frowned. "I know that I am thanking God with every breath. It would be good if more people knew how to do that."

"Anna?" Arumaeus said.

"People like me. Well, it is true. As soon as you are well enough, I am going to visit these 'Red Cross' people and learn. What would have happened if you had been at home when you fell? It would have taken far too long for one of the servants to summon a physician."

* * *

"They tell me that the condition is not immediately threatening," Arumaeus said. "My interpretation of this, Erasmus, is that while I am not in danger of dying tomorrow, neither am I likely to make my allotted four score and ten—or more, if I should have the strength. Which means that it is time for me to take thought for the future. I want an obvious successor in place when my time comes to die. You are already carrying far too many administrative burdens for the university as a whole—president of the faculty senate, among others. So, I have been thinking..." He gestured toward an engraved portrait hanging on the wall of his study. "We need his mind, Erasmus. We need his mind."

"Hugo has always refused to convert to Lutheranism, Dominik."

"True. Nor will that change. But. Other things are changing. One of those things, I am quite certain, is that we are no longer the university of the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar, but one of the universities of the State of Thuringia-Franconia. So, clearly, while the members of the theological faculty, certainly, must be Lutheran—why do the members of the other faculties still need to be Lutheran?"

"And I, having such heavy administrative burdens for the university as a whole, am expected to . . . ?"

"Push the change through. President Piazza will back you."

Ungepauer nodded.

"As rapidly as possible. As for me, I will write Hugo today."

"He's still in Oldenburg, isn't he?"

"Count Anton Guenther has made him welcome. But, given the ages of his sons, it can scarcely come amiss for him to take a faculty position at a good university. The perquisite of free tuition for them alone . . ."

Ungepauer laughed. "For his sons? What if, the way the world is changing, what if he wants free tuition for his daughters as well? I have heard that Cornelia is a great 'fan' of Ms. Melissa Mailey. There are women students in the medical school already. How fast do you want me to create miracles in the faculty senate?"

Arumaeus looked startled. Then . . . "Piazza would back you on that change, as well. As unsettling as it may seem to us. In Prague . . . and, Erasmus . . ."

"Yes."

"Anna insists that I must eat vegetables. Without butter."

"Oh, dear," Veleda Riddle said. "Are you certain you should have come, Dean Arumaeus? In this weather and so soon after your heart attack."

"The train is a very comfortable mode of transportation. Warm and dry. I assure you, gracious lady, that I am feeling entirely well again."

"And, to ensure that you continue to do so, I confess, Sam Krapp brought me a note from your wife last week that I am not to feed you whipped cream any more. The hot chocolate, I think, is still fine." She paused and poured the cups full of the aromatic brown beverage. "Otherwise, though." She pulled the napkin off the refreshment tray. "Edna and Irma brought them to me especially for you, from their greenhouse."

Dean Arumaeus tried to feel suitably thankful to God for a small dish of fresh cherry tomatoes in a world that contained whipped cream.

"I take it that the registrar at Jena hasn't identified a clergyman for us, yet. However, it's no longer so pressing. Master Massinger, the playwright, has persuaded someone to come for a few months at least. A poet, he says, as well as a clergyman, interested in exploring the future course of English literature. Leopold Cavriani says he knew the man's brother when he was in the Levant—another merchant. The family name is Herrick. I don't suppose you would have met them when you were at Oxford, for this young man was barely ten years old when you were in England, and later attended St. John's College at Cambridge in any case. He's going to take a detour on his way, see Archbishop Laud, and obtain the appropriate authorization. So if, within the next half year, you should hear of someone more permanent, I will be most grateful, but we should have a temporary solution for our little parish by May.

"Now if you would excuse me, if you and Tom are all set? I have a League of Women Voters meeting this afternoon."

Her husband sighed as she bustled out. "Veleda is very energetic."

Arumaeus nodded. "Most women are. I am becoming more sure, the longer I live, that the 'weaker vessel' concept must be purely theological, since it does not appear to apply in practice. So. What is on your mind, Tom?"

"Do you know a man named Friedrich Hortleder? Well, I'm sure you know him, but do you know him well?"

"I was the adviser for his doctoral thesis. Yes, I think I know him well."

"Gary Lambert, the business manager over at Leahy Medical Center, has gotten engaged to his daughter. Nice girl, as far as I can tell. But Hortleder has drawn up a pre-nup . . ."

Arumaeus frowned.

"A marriage contract. We called them 'pre-nuptial agreements.'"

"Oh, of course. Obvious, now that I think about it. I have met Herr Lambert, since Leahy is in cooperation with the medical school in Jena."

"Gary had Laurie Koudsi look it over for him. It has more clauses than the constitution of the United States of America did. She thinks she's in over her head. She is in over her head, and she's smart enough to know it. So if you could do me a favor and recommend someone with really extensive experience in down-time family law—someone Gary can afford, you realize . . . The hospital doesn't pay him a princely salary. Reasonable, but not lavish at all."

"That may be Hortleder's main concern. He's done well for himself—very well, considering how humble his background is."

"I want to make sure that it's fair. That Hortleder doesn't throw in some sneaky wording that could mess things up down the road."

"Oh, yes. I've seen some of those. Provisions that even if the first wife should die childless, upon the husband's death the amount he settled upon her is to go to her relatives rather than reverting to any heirs of his subsequent marriage. With interest. Don't worry. I'll see to it that he's taken care of."

"I do thank you. Very sincerely. With all the weddings coming up, next month and in May, I'm beginning to feel that we really are creating 'the ties that bind.'"

"Or, possibly, forging links in a durable chain. One by one."

"Where did I put that file? Back in the cabinet, I suppose." Thomas Price Riddle started to pull himself to his feet.

Mary Kat jumped before anyone else in the seminar could move. "I'll get it, Grandpa." She planted a kiss on the top of his head as she went past him.

"You shouldn't be serving me, child, in your condition."

"I'm pregnant, Grandpa; not an invalid."

"I'm glad," Marie van Reigersberch said. "If you ask me, with Ostfriesland joining the United Provinces, we are too close to the Dutch border for comfort. I have no desire to smuggle you out of prison in a book chest again. That was nearly fifteen years ago. I'm getting too old for that sort of thing."

Hugo de Groot, Latinized as Grotius for academic purposes, obediently said, "Yes, dear."

"What made you change your mind? Finally? It isn't as if you hadn't received other invitations from universities in the USE. Some of them, as in Hesse, Calvinist."

He reached across the table. "The book, I think. The book that Dominik sent me."

"You must have read that book fifty times since we received it right after the New Year. I read it, yes. Once. It was enjoyable. Especially the clues. I would like to read more of these 'detective stories.' But I don't see the fascination for you."

"It's seeing the fruit, Marie. Seeing the whole development from the seed to the fruit.

"The stories about this Uncle Abner are set in West Virginia. Where the Ring of Fire came from. And in them, I can see the fruit. Set in a time when this 'West Virginia' was a remote place. 'Backwoodsmen,' Dominik wrote to me, and sent an explanation of the word written by a young lawyer named Samuel Krapp. Excellent work, by the way. Outstanding explication."

He turned to his oldest daughter, so much help in dealing with the burden of his extensive correspondence. "Cornelia, take a note to Arumaeus, please. I want this Krapp for my personal assistant, please, if he can arrange it."

Then he looked back at Marie. "The ideas that are so slowly, painfully, and incompletely born from my mind—by the time Melville Davisson Post wrote about his Uncle Abner, they were ingrained in an entire culture, so much part of it that the people who held them were scarcely aware of them. They were as natural to them as the air they breathed, the earth upon which they walked.

"It is wholly improbable that people whose culture descends from the English I met on my diplomatic mission for the States General in 1613 ever absorbed such modern ideas. Rarely have I encountered such an intransigent and stubborn group—even the Counter Remonstrants scarcely equal them. One would think them totally blocked from ever accepting new ideas at all—they could not even think an occasional new thought about commercial relations in the East Indies. But, somehow, their descendants did.

"I want to see them, Marie, before it is too late for me—this people from the future who have brought the first fruits of my mind back to our troubled times. Not in completed form, perhaps. But people who assume that the foundations of my political thought are not revolutionary, not dangerous, but simply the way that things are. Not a wishful 'way they should be,' but the way they are. That I want to see."

"Not this year," Dorothea Susanne Arumaea verh. Fomann said. "I haven't passed your grandfather's 'bar exam' yet, Mary Kat. But next year. Next year I will tell my father and husband that if they let women study philosophy and medicine at Jena, then they must let them study law as well. It is only logical. I hope it doesn't give Papa another 'heart attack.' I truly do love him. But it is only reasonable that they should start with me—a respectable older married woman whose husband and father are right there to ensure her welfare and prevent any rowdy behavior by the other students. It makes much more sense than to have some young, unprotected girl bear the burden of being a pioneer."

Mary Kat looked at her. "I think you have a legal mind. Which isn't really surprising, under the circumstances. A person couldn't even get into a 'nature or nurture' argument in your case. Talk about mutual reinforcement."

Thomas Price Riddle looked at his seminar students. "Some months ago, I think, I was about to tell you a story about my uncle, Abner Patton. I was thrown off the track and somehow never got back around to it. While it's probably not relevant to anything I'm supposed to be teaching you, and certainly won't have any impact on the course of history . . ."

* * *