I'd gotten a decent night's sleep after the hard ride back from Eisenach. Much of Grantville had stayed up late celebrating their victory over the Croats, but I'd slept through most of it. After breaking my fast, I wandered over to the police station to see how the Grantville police were dealing with the aftermath of the raid two days before.

"Sergeant Leslie," Angela called, smiling. "Am I glad to see you!"

Before I could reply, the phone rang and she picked it up. "Grantville Police," she said, and then paused. I listened to half a conversation while she took notes. Angela Baker is a sweet young woman, but I'd seen her handle some tough situations in the months that I'd served as Mackay's man with the Grantville police.

She picked up her radio microphone as soon as she hung up the phone and transmitted a terse message full of the ten-codes that the American police seem to love. The message was acknowledged by what seemed more a squawk of static than words, but she seemed satisfied.

"Where is everyone," I asked, after she finished with the radio.

"Out," she said. "While everyone else celebrates, we work. That call was about a wounded Croat cavalryman who crawled out of the woods east of town. We've had some cases where they're still armed and dangerous, but some died before we got to them. Add to that the fact that the king is in town with his cavalry, and we're busy. What I was going to say is . . ."

The phone rang again, so again I waited while she took notes. When I first began working with the Grantville police, I thought girls like Angela were menials, but I'd been wrong. Her job wasn't just to answer the phone and relay messages, it was to decide what mattered and what could wait. If something did matter, she had to know who to tell.

"A horse wandered into someone's back yard," she said, shaking her head as she put down the phone. She looked up at me and went on in a more serious tone. "John, we're short handed, and I have a call here that needs attention now. I know you're not officially Grantville police, but could you go out and take a look at this for us?"

"What is it?" I asked.

"The power plant phoned just before you walked in the door. They say they think they might have been attacked."

"They think?" I asked.

"Weird, isn't it. The rest of Grantville is darned sure it was attacked, but out at the power plant, they just think. Could you ride out there and see what's going on? Take notes, collect evidence."

Ten minutes later, I was on my horse on the road up Buffalo Creek. I'd hoped to spend the day helping celebrate Colonel Mackay's wedding, but I knew how much Grantville depended on electric power. In the past few months, Grantville's electric powered machine shops had become the key to supplying the king's new artillery.

It's a three mile ride to the power plant, but even before I got to the fairground on the west side of town, the whole atmosphere changed. Where the center of town was bustling with work cleaning up after the Croats, the west side was calm. I saw no broken windows and no bullet scars on buildings. If any Croats had made it west of town, they'd left scant evidence.

Not long after I crossed the railroad tracks at Murphy's run, the valley turned, giving me a view of the great cliffs south of Schwarzburg that mark the border of Grantville's land. A bit over a year before, Grantville and a round chunk of America from almost 400 years in the future had been plunged through a ring of fire into the center of Germany. The ring of cliffs around Grantville mark the mismatch between the German mountains outside and the American mountains inside. I've been in and around Grantville for most of a year now, and it's still terrifying to think about what God or the Devil did in that instant.

As the valley straightened out, the castle at Schwarzburg and the power plant below it came into view. A year ago, there was just a small cluster of houses by the power plant. Some people called it Spring Branch, after the stream that used to flow into Buffalo Creek there. Now, the Schwarza River flows into Buffalo Creek at Spring Branch, and the village has more than tripled in size. The power plant workers put up some of the new houses, a cluster of what the Americans call mobile homes, but the biggest growth started as a prisoner of war camp just west of the plant. By fall, the camp had become a refugee camp, and now that was fast becoming a permanent village, housing for workers at the power plant and at the new businesses growing up around it.

"Someone here called the police?" I asked, at the power plant's guard house.

"You not police," the guard said, looking at me through the woven steel wires of the fence around the place.

"Nein," I said, switching to German. The old man didn't look like he could guard much of anything, but he controlled the gate in the eight-foot high fence around the plant. "I'm John Leslie, cavalier with the Green Regiment. The police are a bit short handed, so they asked me to come out."

"I'll phone," he said, suspiciously, walking back into the guard house.

While I waited, I looked. I'd seen the power plant from the road many times, but I'd never been inside the fence. The place is immense and strange. Tall stacks on the east end of the building give off faint brown trails of smoke. The walls of the plant are iron in some places and brick in other places, and they must be fifty or a hundred feet high. It's not a fortress, but if it weren't for the huge windows, it would be easy to mistake it for one.

"Come in," the guard said, walking out to the gate. He pulled it just wide enough for my horse. "Tie up your horse this side of the railroad track, the grass is good there. Someone will come for you."

A man came around the corner of the plant as I took care of my horse. "Mr. Leslie?" he said, in American style. "I'm Tom McAndrew. You're here instead of the police?"

"I've been the Green Regiment's man with the Grantville police for most of a year now," I said, taking out the pad of paper Angela had made me take and writing down Tom's name. "They're a bit short handed what with the raid and the king's visit and all, so I said I'd help. What happened here?"

"Someone's been shooting at the plant," he said, leading me around the corner.

"It looks like it'd take a cannon to hurt this place," I said, looking up at the thick brick walls. "Of course, those big windows are a weak point."

The west wall of the place wasn't as high as most of the walls facing the road. Perhaps only 30 or 60 feet high, and parts looked newer. The windows began halfway up and ran almost to the top. If they'd had colored glass, they'd have belonged in a cathedral.

"They're not aiming at the windows, they've been shooting at our switchyard."

"Your what?"

Tom paused, and then pointed. "That's the switchyard," he said, pointing to the place where all the different electric wires converged on the plant. A line of tall towers carried six great wires off to the south while wooden poles carried three great wires off to the north. Smaller lines also came together at the place. There was a ring of high wire fence around the yard, and inside, a maze of strange stuff, all made of gray metal except for some parts that must have been green glass or brown glazed fine china. A faint hum seemed to fill the air as we came near.

"I'm afraid I don't get it," I said, dismayed. "I'm just a poor Scot, they should've sent an American."

Tom smiled wryly. "Don't worry, most of the folks in Grantville don't understand this stuff either, but I suppose they do their best to sound like they do around downtimers. The switchyard is where the power from the plant gets switched onto one line or the other. Those boxes with two connections each are circuit breakers to cut off power to the power line if there's a problem."

"Connections?" I asked, puzzled. "You mean those pillars of crockery coming out the top?"

"Right," he said, grinning. "Now, the big boxes with six connections each are the transformers, they change the voltage."

"Voltage?" I asked, feeling lost.

"That's a measure of how strong the electric power is," he said. "Forty volts is enough to kill a careless man, less if his skin is damp. When people turn on an electric light, that's just one hundred and fifteen volts. The bus bars are those three pipes that go across the top of everything. They run at thirty-five kilovolts, that's thirty-five thousand volts, three hundred times stronger than the power for an electric light. The three main circuits going out of the plant are one hundred and thirty five kilovolts. Of course, there's only one that still works, the one that goes over the hill to the mine."

I shook my head, lost in all this detail. "So how do you know someone was shooting at it."

Tom pointed. "Look at the insulators."

"Insulators?"

"You called them towers of crockery. They're glass or porcelain, crockery if you wish. Their job is to support the bus bars and the wires without letting the electricity leak out. Electricity only goes through metal, it can't go through insulators. The bigger insulators are for higher voltages. Anyway, take a look at the insulators holding up the bus bars."

I looked, and indeed, two of the insulators holding up one of the bus bars were shattered. Looking at the gravel below, I could see fragments of broken crockery.

"I see," I said. "Nobody seems to be in a panic, though. Why is this important."

"Because it could have shut down the plant. It should have. I wouldn't have expected the bar to hang in the air like that. The two insulators at the other end of the bus bar must be holding most of its weight, and the rest is being taken by the rigid feeders that drop down to the two newest transformers below. If the bar had sagged down just a bit more, we'd have had an electrical explosion and the power plant would probably have been dead for at least a week while we fixed the damage. As it is, we've got a problem because we only have one spare of that insulator. We've taken it to a potter so she can try to make a duplicate."

"You think it was done with a gun?" I asked, looking around. The closest the outer fence came to the switchyard was about ten rods, either from the south across the creek or from the edge of the refugee camp to the west. "It can't have been done with a common matchlock, it's too far. Whether it was German or American, it was a long rifle. If we could find a bullet, that would help."

"I have the key," Tom said, "but it's dangerous in there. Keep down, don't get tempted to climb up on anything."

"I heard you talking about thousands of volts, when what, forty are enough to kill a man."

"Right," he said, as he unlocked the gate in the switchyard fence.

I wasn't happy in that switchyard with the humming of the electricity all around me, but I did my best to ignore it. It was the broken insulator on the ground that I wanted, not anything up high. I didn't move anything, but just looked at the pieces where they'd fallen. "Do you see," I said, pointing to the shattered pieces of one insulator, and then pointing up at where they'd come from.

"What," he said.

"The pieces are scattered, but they're mostly east o' where they came from. I'd bet the shooter was over there somewhere," I said, waving at the refugee camp to the west.

The pieces of the other insulator were scattered in the same way. I wanted a bullet, so my eyes were on the gravel. Lead doesn't bounce very well. If a bullet hit an insulator head on, it would likely drop to the ground right under it.

"Look there," Tom said, pointing at the wall of the power plant.

"What?" I asked, straightening up to look where he pointed. There were fresh bullet scars on the brick wall of the power plant. It was obvious that a shooter trying to hit an insulator at 50 yards was bound to miss a few times.

"That's good," I said. "But help me find a bullet before we leave here."

We looked for another few minutes before I found a smashed bullet. "Take a look," I said, holding it in my hand.

"It was a round ball, wasn't it."

"Right," I said. Not with a flat bottom, like your rifles shoot, but it was shot from a rifle, you can see the grooves. We're looking for a downtime marksman, I think, perhaps a jäger."

"Yayger?" he asked, while I pocketed the ball and a few pieces of shattered insulator.

"Professional hunter," I said. "They usually use good rifled guns."

The area under the scars on the side of the powerplant was weedy, there was no hope of finding a bullet there, but standing under the scars on the side of the building and sighting back through the switchyard toward the refugee camp, it was obvious where the shots had come from.

"Want me to go with you?" Tom asked, as we stared at the building the shooter must have used.

"That would be nice. Back through the main gate?"

"Faster through the west gate," he said. "The railroad used to go out that way, before they pulled the track last summer. I have the key here."

When I'd first seen it, the refugee camp had been nothing but a few parallel rows of light sheds. Just about every time I'd visited, there'd been changes. What had been sheds had been closed in by winter, and with the coming of spring, the pace of construction had increased. The shooter's building had a new second story, and as we came up to it, a roofing crew was at work adding a good slate roof on top.

"Hey, who you," a German carpenter asked, as we stepped inside.

"I'm from the power plant," Tom said. "John is with the Grantville police. Who are you?"

"Johann Schneider."

While I tried to figure out what question to ask, I wrote down his name. "What happened here during the Croat raid?" was the best I could do.

"Well," the carpenter said, answering in German, "the news of the Croats came before we got to work. We decided to lock the old prison camp gates and move the women and children into the inner houses. I think we could have held off a cavalry attack for a long time."

I nodded, looking around. "You're probably right. Horses are no match for a woven wire fence with barbed wire on top. You had guns?"

"A few," he said. "Mostly matchlocks, but enough to keep an attacker from trying to cut his way through the fence, and three of us had American pistols."

"No rifles?"

"No," Schneider said. "Everyone who had a gun had it out. I didn't see any rifles."

"So what happened afterwards. When did you get back to work here?"

"When news came of the victory, we had a bit of a celebration. It was time for the noon meal, so it was afternoon when we got to work."

"Did you see anything in this house when you got back to work?"

"Like what?" he asked, and I was stumped. I didn't want to ask for evidence of someone shooting at the power plant. I'd learned from the Grantville police that it was bad to ask leading questions. "Well, any sign that something odd had happened here."

"Now that you mention it, there was something," he said, frowning. "That window was broken out, and there was a sort of sulfur stink in the air."

The window he pointed to had only a few fragments of greased paper around the edges. It faced the power plant, and someone had torn out the paper. When I walked over to the window, I could see powder burns on the sill. Someone had fired a black-powder rifle out the window from close by. "Tom? Take a look."

Fortune didn't smile on us when we asked around, nobody remembered hearing the shots fired. People told us that the power plant makes odd noises on occasion, and it seemed likely that the shooter had managed to muffle the noise of his gun by shooting from inside the house.

Around noon, Tom suggested we break for lunch and recommended a tavern out by the main road. The place had decent food, and they'd set up tables in the shade of a big tree. Halfway through our meal, when the serving maid came to ask if we wanted more beer, I thought to ask the same questions I'd been asking in the camp.

"Around the time of the Croat raid, did you happen to see anyone around here with a long rifle?"

She frowned. "There was a man here the night before who had a big flintlock rifle. He said he was visiting a friend in the camp."

"Can you describe him?"

"Weatherbeaten, thin, he had a brown horse with a white cross on its nose. By his accent, he was Franconian."

"Have you seen him before then, or since?" I asked.

She hadn't. I paused, puzzled, and then looked across the table at Tom. "A jäger, it would seem, and from Franconia. How in creation would such a man know to shoot at your, what do you call them, insulators."

"It's an obvious way to attack a power plant," he said.

"Obvious to you," I said, "But you had to spend half the morning explaining things to me enough that I could understand what he'd done. Someone here, someone working in your plant, must have taken the time to explain the same things to that man, or more likely, to whoever hired him."

"You think we have a spy in the power plant?"

I nodded.

* * *

When I got back to the Grantville police station, Angela Baker asked what I'd found. When I told her, she immediately dialed the telephone and asked for Chief Frost. "Yes," I heard her say "I know he's at the wedding banquet, but he should hear this himself." There was a pause. "Yes, I suppose it's poor form to walk out on the king, but if I can't get Chief Frost, then I need to speak with Mackay immediately."

She looked up at me with a grin. "I still can't believe we have a king here in . . ." Someone on the other end of the telephone must have spoken, because she stopped suddenly and then handed me the phone.

"John Leslie here," I said, using my best telephone manners. It was Chief Frost.

I went on to tell what I'd seen at the power plant, leading up to my guess that there was a spy in the plant to teach a German huntsman what exactly he needed to shoot at.

"Good Job," the Chief Frost said. "And thanks for helping cover for us when we're stretched thin. I'll mention your work to Colonel Mackay, and please, write up a proper report, or have Angela help you write it up. I'll forward a copy to Rebecca."

I didn't expect Chief Frost to say he'd forward a copy to Rebecca Abrabanel. To hear Grantville's policemen talk, you'd think nobody ever reads their reports. Now, my report was going to be read, not by some clerk, but by one of the most important people in Grantville.

Angela was a big help with the report, but we took frequent breaks when the telephone rang or a garbled burst of static on the radio needed action.

On one of the telephone calls, Angela put her hand over the telephone mouthpiece. "Power plant again," she said to me, and then uncovered the mouthpiece. "I think you should speak to Sergeant Leslie, he's the one who figured it out this morning."

When I took the receiver, the man on the other end introduced himself as Scott Hilton. "I'm the steam engine project shift supervisor for the power plant. Tell me why you think there's a spy in the plant," he said.

When I finished answering his question, he sighed. "I hate to say it, but I don't think this is our first attack. When I heard there might be a spy here, I didn't want to believe it, but at the same time . . ." He stopped, and there was an uncomfortable pause. "Well, I wanted to hear it from you before I go off half cocked."

I had to grin at the American expression comparing a man to a half-cocked pistol. "So are you fully cocked now?" I asked.

"I suppose so," he said, with a chuckle. "As I said, I think there were other attacks on the plant."

"Why?"

"We've had accidents," he said. "We expected some accidents, but there've been some odd ones. We're trying to build machines none of us are really prepared to build, you know."

I didn't know, but I didn't interrupt him.

"When you've got enough plain ordinary accidents, it's easy to think that everything that goes wrong is an accident. Now that we know someone's trying to attack us, I'm pretty sure that some of those accidents weren't so accidental. I just talked it over with Landon, my boss, and he agrees. There are two that we're pretty sure of, a main bearing failure and a cylinder head that burst."

"I'm afraid I don't understand. What's a main bearing, and what's a cylinder head."

He paused for a few seconds. "Tell you what. My wife and I will feed you dinner tonight, and then I'll give you a quick lesson on steam engines. That way, when you do come out to the plant, things'll make a little sense."

He gave me directions to his house before he hung up. All the while, Angela was watching me. "It sounds like you're not done with the power plant," she said.

"It seems that there might have been other attacks."

"Let's finish today's report first, before you start on tomorrow's work," she said. "Tomorrow, take better notes so this job won't be so hard!"

* * *

Scott Hilton lived up the slope on the northeast side of town, far enough from the main roads that the Croats hadn't gotten into his immediate neighborhood. The Hilton house was what the Americans call a foursquare, two stories, with bedrooms above and living area below. As I started up the steps to the large front porch, the silence was shattered by a boy's bellow.

"Ma, he's here!"

Two boys disappeared into the front doorway as I stepped onto the porch. As it developed, there were five Hilton children. Lisa, the oldest, tried to help control the younger ones. Hans and Jacob were the two who'd announced me, and there was a toddler underfoot as well as a baby. There was also a middle-aged German woman, Maria.

Dinner was noisy. Sylvia, Scott's wife, seemed to thrive on the disorder. Between interruptions, she managed to give a short history of the family. "Hans and the two babies, they were the Zimmermann family, from a little village north of here. Maria took care of them after their place was burned out. We took them in after they showed up at church."

"Mister Hilton, how long have you worked at the power plant," I asked, as the children's full stomachs began to quiet them down.

"About a year, Sergeant. Before the Ring of Fire, I worked in Fairmont, that was a town off beyond where Rudolstadt is now. When they asked if anyone knew anything about steam engines, I said yes. I've been at the power plant ever since."

Sylvia interrupted. "The one thing Scott didn't tell me when we got married was his fixation on steam. Just about every weekend, it seems, we would go traipsing off to the darndest places to take photos of greasy old pieces of junk."

He chuckled. "Right, only now, that photo collection is a gold mine and I'm working full time, and then some, trying to recreate some of that junk."

"You're not going to show him your photo collection!" she said.

"No," he said, pushing himself away from the table. "Come down to the cellar, I want to show you a little steam engine."

There was a half-cellar under the downhill side of the house, and half of that was a small workshop. After Scott turned on the light, he pulled a tray of machinery off of a shelf.

"This here's a toy steam engine," he said. "My father brought it back from Germany when I was a kid. This half is the boiler," he said, pointing to a shining round barrel a bit bigger than my fist. "It was supposed to burn a special fuel, but I ran out of that years ago, so I stuffed the burner with rags and if you soak it with alcohol, you can make it work. Let me fire it up for you."

Five minutes later, with the boiler half full of water and the burner rag saturated with gin, blue flames engulfed the boiler and a puddle of blue crept out from the copper shell around the boiler.

"Don't worry about the fire," he said. "So long as it stays on the metal base, we won't burn down the house. While we wait for the water to come to a boil, take a look at the engine itself."

There was a wheel, he called it a flywheel, and when he spun the wheel with his fingers, it cranked a pair of plungers in and out of a metal post off to the side of the flywheel. The plungers were piston rods, and the metal post held the cylinders.

"Why is this piston rod bigger than that one," I asked, only to find out that there was more to learn. There was only one cylinder and one piston rod. The smaller rod was called the valve rod.

About then, the boiler began to whistle. "That's the safety valve," Scott said. "When the boiler is up to pressure, it lets off the extra steam into a whistle. That tells us it's time to run the engine, and letting off the extra steam keeps the boiler from exploding."

As he spoke, he turned a little wheel with his fingertips. "This is the throttle valve," he said, as steam began to hiss out from around the piston rod and the valve rod. "Give the flywheel a bit of a spin with your finger."

I did, and to my surprise, the flywheel began to turn faster and faster, until the machine was humming and the spokes and other moving parts were nothing but a blur.

"Too fast," he said, turning the throttle wheel slowly back. The engine slowed, until it was chugging along at the tempo of a fast march.

"What makes it go?"

"There's a piston in the cylinder, and the steam can push it from one side or from the other. The piston pushes the piston rod, and that turns the crank. Each time the piston reaches one end or the other of the cylinder, the crank slides the valve the other way. That reverses the direction the steam is pushing the piston."

"So what use is it?" I asked, fascinated but puzzled.

"This one is no use at all," Scott said, grinning, "except as a toy for overage boys like me. What we're trying to do out at the power plant is build fourteen machines like this, except a whole lot bigger. Those machines will be able to generate all the electric power Grantville needs."

"But you already have a power plant," I said.

"Yup, but the machines in that plant need supplies we can't get from anywhere in the world, not since the Ring of Fire. We might be able to run the old machines for another year, if we're really lucky. Machines like this toy, though, we can make all the parts ourselves and we don't even need special oil. Beef tallow should work just fine to oil it, and if we can get enough whale oil or even olive oil, that'll be even better."

"Should we add more fuel to the fire?" I asked, as I noticed that the blue flames around the boiler were almost completely out.

"No, this fuel was meant to be drunk, not burned," he said, picking up the toy steam engine and blowing out the last remaining flames. "Come upstairs and we'll share a drink while I tell you something about the problems we've been having."

He put the toy steam engine back on its shelf and picked up the bottle of gin before leading me back up the stairs. "Have you ever had a Martini?" he asked, on the way up.

"A what?"

"Here, sit, I'll make you one," he said, waving me into his parlor. "I've had a bit of trouble getting Vermouth, but I think I've finally got my hands on something that works."

He disappeared into the kitchen with the bottle of gin, and in a minute, came out and handed me a glass of cold clear liquid with ice cubes and a pickled olive floating in it.

"To the king," he said, raising his glass before he took a sip.

"And to Grantville," I said, returning the toast. I'd heard enough of the American attitude toward nobility in general to understand that his toast was unusual. I imitated him, taking just a sip of my drink after the toasts.

Scott launched into the history of the power plant over his drink. "Unit Five, that's the big turbogenerator out at the power plant. It isn't likely to outlast the year. Right now, it's generating almost all our electric power, and we've got to build replacements. We knew that much as soon as we came through the Ring of Fire. The oil filter system and oil are our big problem. We've even got two guys trying to re-refine the oil, but even if they're successful, something else will probably go wrong."

I was totally lost, but one thing puzzled me more than all the rest. "Unit Five? Does that mean there's also a Unit Four?"

"I asked that too, after I started at the plant. Each new generator at the plant gets a number, in order. When they built the plant back in the 1920's, over seventy years before the Ring of Fire, it was a much smaller place, with two units, numbers one and two. They were only a few megawatts each. Then they enlarged the place in the 1930's and 1940's and put in two new units, three and four. Those two might have added up to fifty or a hundred megawatts, and once they were working, they scrapped one and two. Now, the hall that used to hold one and two is the plant machine shop. After World War II, fifty years before the Ring of Fire, they replaced Units Three and Four with Unit Five. That's about two hundred megawatts. The space where Units Three and Four used to be is where we're building our new units."

"What's a megawatt?" I asked, befuddled. "Are they like the kilovolts I heard talk of this morning?"

"Yes and no," he said, launching into a confusing description of the difference between force and power. I must have looked baffled, because he gave up halfway through, took a sip of his drink, and started over. "Think about a mill," he finally said. "You can measure the power it takes to turn the millstone in watts, or you can measure it by how many horses it takes to turn the wheel. One horsepower is about 750 watts. Anyway, two mills might need the exact same amount of power, but one could get that power from a high wheel with just a trickle of water, while the other gets it from a low wheel in a broad stream. You can think of volts as the height of the fall."

He paused to pick the olive out of his glass and pop it into his mouth. "Ah, these Italian olives are pretty good."

All I had left in my glass were two cubes of ice and an olive, so I imitated him. I don't eat olives very often, but it did seem better after soaking in my gin martini.

"Earlier, you said you'd had lots of trouble with accidents," I said, after spitting the olive pit into my glass. "And then you said you expected lots of accidents. Why?"

He sighed. "We're in way over our heads, that's why. Nobody in Grantville has ever built a steam engine bigger than a few horsepower, and now we need to build an engine with a thousand horsepower. Andy Frystack has built little engines, and he's a good machinist. The people at the power plant know steam, but not piston engines.

"Then, think about the size we need. The engines I've tracked down that put out a thousand horsepower all run over a hundred tons of iron, and we want 14 of the things. That's a lot of iron. Even if we can get the iron, who around here can cast pieces that big?

"Accidents? We've had castings break. Bad foundry work is the obvious explanation. We've had steel bolts snap. We might have made a mistake guessing the force they could handle. We've had bearings fail for lack of oil. We're used to automatic oiling systems, we probably didn't oil them enough. We've been lucky, so far. Not too many pipes have burst, and nobody's been killed, but we've come very close to catastrophe.

"Before you go inside that plant, I want to make sure you understand that it's a dangerous place."

"I got a lecture on the danger of electricity when I visited this morning." I said.

"It's more than that," Scott said. "We're working with chunks of iron that weigh a ton or more. Chunks of stone, too, for the engine foundations. Be careful what you walk under. Steam pipes are hot. We work with superheated steam at four hundred pounds of pressure per square inch. That's a high enough pressure that it is like working with gunpowder. Steam pipes can explode like bombs, and the cylinder of a steam engine can shoot a piston just as well as a cannon can shoot a cannonball."

* * *

Scott Hilton met me at the power plant the next morning and led me into the building. "This is the hall they made for Units Three and Four," he said, as I gawked at the scene. "Now, we've built Unit Six at the far end, and we're building Units Seven, Eight and Nine."

The room was huge, filling perhaps a quarter of the whole power plant. Huge windows along the south and west walls spread a soft light through the room. The place reminded me of a cathedral, except for huge machinery and construction toward the east end and a work crew digging a pit toward the middle.

Scott led me to the construction area. A crew of masons were at work there, filling a newly dug pit with stonework. Scott's explanation mostly went over my head. "This is the foundation for Unit Eight," he said. "Parts of it stand up high to hold the cylinders, but we need access to the steam and condensate pipes, and of course, there's the pit for the generator and flywheel."

While we watched the masons, a huge door at the west end opened to admit a four-horse team hauling a heavy freight wagon.

"Ah," Scott said. "They're delivering a stone for Unit Eight. Watch."

At first I didn't notice, but there was great bridge spanning the width of the room and it was moving toward the freight wagon. As a huge hook lowered from the bridge, I realized that it was a crane. When it reached the wagon, the teamsters hung their load from it, a single large stone.

"How much does the stone weigh?" I asked.

"About two tons, solid quartzite," Scott said. "It's quarried from the ring wall north of Schwarzburg, less than a mile from here, all downhill for the heavy stones. The little stones go to that new warehouse they're building in town, we keep the big ones."

As he spoke, the crane silently carried the stone toward the awaiting masons and lowered it onto a bed of fresh mortar.

"What's all that stuff," I asked, pointing to piles of ironwork stacked along the wall beyond the masons.

"Parts. We're getting parts from foundries and forges scattered all over. Some workshops are better at little castings, other can do big ones. Some forges do wrought iron, some can give us the little steel parts we need. When the parts come in, we line them up over there until we're ready to use them. Let's look at Unit Seven. There, we're starting to put things together."

He led me to the narrow space between Units Six and Seven. Six was a huge version of the machine I'd seen in Scott's basement, churning away at double-time and making a quiet pop-pop noise as it worked. About half of the big iron pieces of Seven were in place, with a group of men hard at work on one of the big pieces.

"They're turning the low-pressure cylinder right now," Scott said.

"Turning?" I asked. "Looks like it's not moving at all."

"Boring, I should say," Scott said. "See, they've run a boring bar down the middle of the cylinder, between those cast iron centers attached across each ends. There's an electric motor turning the boring bar, and there's a tool on the bar that goes round and round scraping the inside of the cylinder to be exactly thirteen and a half inches radius, as close as we can make it. It's not that different from boring a cannon, but a whole lot bigger around."

Turning to look at Unit Six, I could see similarities to the engine I'd seen the night before, but there were differences. "On your little engine, the valve and the cylinder were right together on the same side of the big wheel, but here, they're on opposite sides."

Scott looked baffled, and then chuckled. "No, my little engine at home has just one cylinder. Here, we have two cylinders, and each has its own valve system. The thirteen inch one on the far side is the high pressure cylinder, the twenty-seven inch one on the near side is the low pressure cylinder."

He must have seen the baffled look on my face. "It's a compound engine. That means we use the steam twice. The high pressure steam is four hundred pounds per square inch. We get half the work out of the steam dropping the pressure to seventy-five PSI, that's pounds per square inch. The low pressure cylinder gets the other half of the work, dropping the pressure to near zero."

I surveyed the immense thing, wondering how I could possibly be of any use. "You said you thought there'd been attacks? What kind of attacks?"

He led me over to the great crank on the high pressure cylinder side. It was whirling around and around, almost too fast to follow with my eyes. "See that thing on top of the main crankshaft bearing?" he asked, pointing to the trunnion bearing behind the crank.

On top of the heavy ironwork was a polished copper fitting a bit bigger than my fist. "That's an oil cup," he said. "It's full of oil, and the oil in it slowly drips down into the bearing. Without oil, the bearing would burn up and wreck the engine."

"Burn up?"

Scott paused before he answered. "Ever see how hot a wagon axle gets if there's no grease on the hub? This wheel is turning so fast that the metal itself will melt if it runs dry."

"So what happened here?" I asked.

"Every half hour, the engine master comes through and tops up the oil in each of the oil cups. A month and a half ago, right after we got this engine working, the bearing caught fire. Afterward, we found that the oil cup was missing, broken off. The engine master swore that the cup was there not twenty minutes before."

I looked at the cup. "But the engine wasn't wrecked?"

"It came close. The engine master was nearby, and when he saw the smoke, he killed the engine. We had to re-turn the axle and replace the brasses before we put the engine back in service."

"So we're looking for someone who knows the engine needs oil," I said. "This engine master you mentioned, I should talk to him."

"Probably," Scott said, "but Franz was badly hurt in the next accident. Come here."

He led me into the space between the two cylinders. There was a confusion of moving parts there, with the great wheel spinning madly not far in front of us. A cast-iron case as big as the great wheel gave off a hum that sounded like the electric switchyard outside.

"What's all this," I asked, and got more than I wanted. The great wheel was the flywheel, the humming case beside it was the alternator, with another wheel inside it called the forty-eight pole rotor. I'd been right about the sound. The alternator was the part of the engine that actually made electricity. The spinning shaft along the side of each cylinder was a camshaft that worked the valves, and the whirligig on the end of each camshaft was the governor that controlled the engine speed.

"My little engine at home has piston valves, but that kind of valve doesn't work very well at high speed. When we started working on this engine design, some of us wanted to use Corliss valves, but the Masaniellos convinced us to do it with balanced poppet valves. They're faster and the parts are easier to machine. The camshaft here works the poppets."

I was totally baffled, except that I could clearly see his finger pointing at the spinning shaft he called the camshaft. "What was the next accident you were talking about?" I asked, trying to bring things back to something I might be able to understand.

"That's what I was getting at," Scott said. "Right after we got this engine restarted, the head of the low-pressure cylinder blew. Steam and hot water sprayed out and it scalded Franz, the engine master I was talking about earlier."

"Blew?" I asked.

"The end of the cylinder exploded," he said.

"Like a burst cannon?" I asked, remembering a gun crew I'd once seen shredded by the final shot they fired.

"The cylinder casting held," Scott said. "This is it, but the head cracked and some of the bolts that held it on pulled out. We had to put in new bolts and use the head intended for Unit Seven to repair it."

"While we were repairing it, we found that the cam for the exhaust valve at that end of the cylinder was loose. We'd just changed the valve timing when the bearing failed, so I can't believe that the key that held it to the shaft fell out on its own. With that cam loose, some of the steam that should have come out through the valve turned to water. The water had nowhere to go and the piston was pounding on it one hundred fifty times a minute. The water had to go somewhere, and with the valve stuck closed, the end of the cylinder exploded."

I scratched my head. "So we're looking for someone who really knows how these engines work. How many of you uptimers know enough to do this kind of damage?"

"Anyone who's ever worked on cars knows how much damage you can do by letting an engine run dry," he said. "The trick with the exhaust valve, though, you really need to understand steam engines to know the damage that can cause. This engine has eight valves total, and there are only two of them, the low pressure exhaust valves, that can wreck the engine if the cams are loosened."

"So it has to be a steam engine expert," I said, frowning.

"Right. And there aren't many of us."

* * *

"How will you prevent it from happening again?" I asked, as Scott and I looked out over the machinery hall. "Some o' those accidents might really have been accidents, and even if we catch whoever did it, there might be others."

Scott scratched his head. "We learn something from each problem we have. We're working on automatic oilers, so nobody has to climb around in dangerous places to get oil into the bearings. After that cylinder head blew, we redesigned the poppets. We needed to do that anyway, balanced valves are harder to make than we thought. Each valve is really two valves on one stem, and our first ones always leaked. The new ones have a spring in them to help get a better seal, but the spring also lets the valve leak if the cylinder goes over pressure, just enough to protect the engine."

About then, a whistle blew. "Lunchtime," Scott said. "There's a lunch room in the plant, or we could go out to eat."

"A lunch room?" I asked, uncertainly.

The place, it seemed, was a room where you could buy food. American style sandwiches, the little cakes Americans call cookies, and a choice of water, milk or weak beer to drink. I've eaten worse, but I'd have preferred better.

Scott looked quizzically at me as I sat down. "You're a soldier with MacKay's regiment, right? How'd you get involved with police work?"

"When the regiment moves into a town, someone has to smooth things over with the town watch," I said. "The watch and the local militia can be our best friends, but if we hit it off wrong, well, they're armed as well as we are. I was pushed into police work, as you call it, by stopping a fight.

"What happened?" he asked, after swallowing a bit of his food.

"MacKay was new to the regiment. This was when we were in the marshes up north. He didn't know the regiment, we didn't know the land, and we set up camp outside this village. The quartermaster went to buy cattle, and suddenly, it seemed we were about to do battle with the militia. I saw it happen, just a little thing, really. MacKay had assigned John Storm to help the quartermaster. John was a wild one, God rest his soul. He pushed a militiaman aside as they walked into the market. Instead of pushing back, the guard pulled his sword."

"You did something?" Scott asked, after I'd eaten a bit of my sandwich.

"Aye, I whacked John on the rump with the flat o' my blade. That stopped it from going bad, but John complained to MacKay. Ever since, MacKay's pulled me into dealings with town watch. By Badenburg, he had me in charge of working with the watch. When we came to Grantville, MacKay asked me to work with your police even before he understood how different they are from the kind o' town guard we expected."

I took a bite, and then pulled him back to the big question. "So who knows enough about the power plant to plan the attacks you've had?"

Scott looked thoughtful as he chewed. "Uptimers mostly. You can rule out most of the power plant staff because they know the old turbines, not the new engines. It's got to be someone who really knows steam. That means me, Andy Frystack, and Andy Prickett. We're the three shift supervisors. Then, there's Vince Masaniello and his sons Lou and Charlie. They're doing lots of consulting on the project, but mostly, they're not here. Dick Shaver and Monty Szymanski have also been involved, but damn it, I can't see how any of them could do something like this."

"If we could figure out who was here when that oil thing got knocked off the trunnion bearing," I mused.

Scott looked up sharply. "We can! We keep a log. Everyone signs in and out of the building. I signed you in today. The guard at the gate keeps a log too, so we know who comes in and out the main gate."

I shook my head. The whole idea of keeping such records was foreign, but it was just like the Americans to do it. The police reports Chief Frost was always demanding were the same kind of thing.

One of the upper chambers of the power plant was almost like a library, with cabinets and shelves full of papers. We went up there after our noon meal. With a bit of help from the woman clerk who worked there, we found the papers for the weeks of the two accidents.

"The first accident happened during the night shift, midnight to eight AM, I was shift supervisor," Scott said, comparing the two sheaves of paper. "That's the least popular shift, with most of the world home in bed. You see Franz Schneider here, the engine master. He signed in and out in his own hand the day the bearing failed.

"Now, the second accident happened first thing in the morning, right after the eight AM shift change, so it could be someone on the night shift who set things up. People take turns working the night shift, and Franz was on the day shift that week. See here, he signed in in his own hand, but he couldn't sign out because he was hurt. It looks like Andy Frystack signed him out after the accident."

Scott continued mumbling over the log sheets, and then leaned back. "The way I see it, Thomas Eisfelder, Charles Martel, and Manfred Kleinschmidt are the three who matter. Those are the downtimers working on our steam engines who were there on the right shift for each accident," Scott said. "I don't think we need to worry about the masons and the common laborers working on the foundations, and the uptime steam crew are out too, since they all think in terms of turbines."

"What if it's a spy," I said, after doing my best to write down the three names. "Someone outside paying off a laborer to fix the engine the same way someone paid off that jäger to shoot at the, uh, crockery insulators in the electric yard outside."

Scott scratched his head. "How would you tell a common laborer or a mason to pull the key from the exhaust valve cam on the low-pressure cylinder of Unit Six? And if they did, wouldn't someone notice them working where they weren't supposed to be?"

"OK," I said. "So tell me why those three mechanics?"

"They're three downtimers who really seem to understand what they're doing. Some people just do what they're told and don't ask questions. Some people ask questions and never seem to learn. These three guys are curious. They're the kinds of guys who figure out how things work. They ask good questions."

I nodded. "It sounds like you want more people like that, but if they're not on your side, they can be dangerous."

"Right," Scott said. "So the next thing to do is track them down and question them, right?"

I shook my head, thinking of some of the American movies I'd seen. Dan Frost had just about forced me to see one particular movie about a policeman, Murder on the Orient Express. "We need to learn everything about them before we confront them."

"Then you need to read their personnel files," Scott said.

The plant had a folder of paperwork on each employee. I had little use for the pages showing the hours worked and dollars paid, but there was more. For each person working at the plant, there were notes written about their work. "Part of my job as shift supervisor is to keep notes on the people working for me," Scott explained. "That way, if we need someone for a special job, we can look through the papers to find who's best for that job."

I needed Scott's help understanding the notes, but the story they told was interesting. Two of the men were from the west side of the Thüringer Wald, not quite in Franconia, but close enough. I couldn't help but wonder if there was a connection with the Franconian jäger who'd shot at the electric yard. Thomas Eisfelder had worked in a mill on the Werra river downstream from Eisfeld, and Manfred Kleinschmidt had been an apprentice gunsmith in Suhl. The third man, Charles Martel, was a French locksmith, a Huguenout refugee.

"So do you want me to set up interviews with them?" Scott asked. "Manfred Kleinschmidt is here now."

"No," I said. "What I want to do is talk to their friends. You gave me their home addresses, you told me when they're supposed to work in the next week. I don't want them to know I'm interested in them."

* * *

It was drizzling when I went back to the police station that afternoon. I dreaded the report writing that Angela Baker was bound to want, and she didn't disappoint me. Angela insisted that I write up the results of my day's work immediately, and Chief Frost was there to back her up.

Angela helped set my day down on paper, and when we got to the three names, she immediately turned from the report. "Vera! I have three names, can you look them up for me? Eisfelder, Thomas. Martel, Charles. Kleinschmidt, Manfred."

Vera was an older woman who worked in the back chamber. When people cursed the reports they had to write, they swore that Vera was the only person who ever saw them. Now, while we finished writing up my day's work, Vera searched through her files for anything the police might know about the three mechanics.

"I have one arrest record," Vera said, a few minutes later. "Thomas Eisfelder, drunk and disorderly at the Thüringer Gardens back in March. Got in a fight with another drunk. Pled guilty, paid his fine. No arrest records for the others."

Chief Frost had walked out of his chamber while Vera spoke. "That's a start," he said, "but you know who might have more? The Red Cross. To get that, you'll need a warrant."

"What?" I asked, and then remembered. "You mean like an arrest warrant?" I'd been with Ralph Oferino when he'd arrested a thief. In addition to a ritual involving reading a list of rights, Ralph had read the charges of theft and sale of stolen property from the arrest warrant.

"Almost. A search warrant is an order from the court that requires the Red Cross to show you their files. Vera will type it up while you finish your report, and then we'll have to get Judge Tito's signature before you take it over to the Red Cross."

Half an hour later, I set off through the rain to find the judge. Vera had telephoned and found that the Judge was teaching a late afternoon class out at the high school. I was a bit annoyed to have to do it myself, but Chief Frost had made it clear that the Judge wouldn't authorize a search warrant unless I was there to answer questions, and he couldn't spare anyone to go with me.

Grantville's high school is almost as far east of town as the power plant is west, down Buffalo Creek past the village of Deborah. I had to hurry because the judge's class was supposed to end precisely at five o'clock.

I'd heard that the Croats had wrecked the front of the school, but I hadn't been there since the raid. Temporary wood panels filled most of the huge window openings by the entrance. As I walked into the building after tying up my horse, two carpenters were at work hanging a new wood door. Despite the damage, the business of the school continued.

I had to ask for help finding Judge Tito's law class. It was classified as adult ed, and it was being held in one of the Tech Center classrooms at the back of the school. On the way there, I passed a sign board listing a number of shops. I would have ignored it except that, among the listings for electrical, carpentry, and automotive, it listed a steam engine shop.

When I found the Judge's room, I heard laughter. Peering through the pane by the door, I saw a middle-aged uptimer in front of the class. He looked vaguely Spanish. The students, mostly young men and a few women, laughed again as I watched them pack up their notes. It seemed that he'd ended his class with a bit of humor. He didn't look like my idea of a judge, but I knew I had to be careful about looks when I dealt with uptimers. Mike Stearns didn't look like the equal of a king, but it now seemed he was.

"Sir, are you Judge Tito?" I asked, after all the students had left.

"Yes, what can I do for you?" he asked.

"Sir, I'm told I need a search warrant," I said, making a small bow as I pulled out the papers. "Chief Frost said we need your approval."

The Chief's warning about Judge Tito proved to be right. For the next five minutes, he quizzed me. He had three basic questions. First, he wanted to be sure that my relationship with the Grantville police was legitimate. Then, he wanted me to explain the crime I was investigating. Finally, he wanted to know precisely why I was interested in any records the Red Cross might have on Eisfelder, Martel, and Kleinschmidt.

After I'd explained my case, he signed the typed copies of the warrant Vera had prepared. "I keep one," he said. "You return one to the police station and take the other to the Red Cross. They'll be closed by now, so you'll want to be there bright and early tomorrow. Good luck figuring out what's going on at the power plant."

On my way out, I decided to poke my nose into the steam engine shop. When I found it, I saw that it was in space that had once been one end of the auto shop. A group of men at one end of the room had an American car hoisted into the air so they could look at its undersides. At the other end, a small group of men was clustered around a pair of middle-sized steam engines.

An old man looked up as I walked over to the engines. "Can I help you?" he asked.

He introduced himself as Dick Shaver, the teacher for the evening steam class, and then invited me to join his students. I just watched and listened for ten minutes, saying nothing. The two steam engines were huge compared to the toy machine that Scott Hilton had shown me, yet tiny compared to the monsters at the power plant. One was turning lazily, making quiet put-put noises. The other was partially disassembled.

Only after the students had been set to work on their tasks did Dick turn back to me. "Any questions?"

I looked at the engine they'd opened up. "You've got the valves opened up, right?"

"You're a downtimer," Dick said, looking a bit surprised. "You know 'bout steam engines?"

"A little," I said. "Scott Hilton showed me round the power plant."

He brightened. "Lovely monsters they're buildin' out there!"

"So what are these machines for?"

"Teachin' and experimentin'. Gotta teach kids how they work, and gotta try new setups. The one we're workin' on was the second we made. Worked OK, but we know how to do better, so we're rebuildin' the valves. Good work for the kids."

I didn't see any kids in the room. His youngest students might have been eighteen, and two of them were near my age. "What kind of students do you get here?" I asked.

"All kinds," he said. "The worst, the best, an' everythin' between. Take Hans there," he gestured at a young man. "He's the son of a miller, grew up aroun' machines. He catches on right quick. The best we get are like that. Had a guy in here last spring, Manfred from Suhl, apprentice gunsmith 'for he come here."

"Manfred Kleinschmidt?" I asked.

"Yeah, that's right. He went to the power plant, didn't he. How's he doin'?"

"Mr. Hilton says he's one of the three best men he's got," I said, wondering how I could get more information out of him. "I didn't know he was from Suhl. Why'd he leave? I thought the gunsmiths there were doing really well."

Dick Shaver scratched his head. "Well, there's two answers to that. He said he was kicked out cause he was sweet on the boss's daughter. Might even be true, but the way I figure it, he probly come here as a spy. Pretty near every master gunsmith wants to learn the secret of our uptime guns y'know."

"You really think he might be a spy?"

Dick smiled. "There's people comin' here from all over to spy on how we do things. Seemed sorta funny at first, but what the heck, we got nothin' to hide. May as well show them the answers, even if they're a mite shy 'bout comin' out ans askin' straight questions." Suddenly, Dick Shaver turned to his students. "Stop! Halt!" he said, before turning back to me. "I gotta see to my students before they wreck that valve seat."

"My pardon," I said, turning to leave. "But before I go, I wonder. You're not teaching how to make guns, you're teaching how to make steam engines."

"How are steam engines like guns?" he asked, with a smile. "Well, for one, you bore a cylinder exactly the way you bore a cannon. Thanks for the visit."

I stopped at Tip's Tavern for supper on my way back into town. That's when it struck me. What Dick Shaver meant when he called Manfred Kleinschmidt a spy applied just as well to me. I was the Green Regiment's spy trying to understand Grantville's police department.

* * *

Claudette Green was in charge of the Red Cross office. She read my warrant closely before sending a young German girl into the back closet to find the papers I needed. While the girl was at work, Claudette looked me over. The look on her face wasn't approving.

"Good woman," I said, feeling awkward. "Is there a problem?"

"What do you know of the Red Cross?" she asked.

"'Tis a Christian charity," I said. "You help those wounded in battle, you help those seeking refuge," I drew breath to say more, but then realized that I'd said all I knew.

"Close enough," she said. "Do you understand that refugees might be less willing to seek our help if they know that our records might be turned over to the government?"

"No," I said, before I realized that admitting so might not have been wise.

"Think about it," she said. "If I could, I would demand an oath that you disclose nothing of what you learn here. Certainly nothing about any man who turns out to be innocent."

"On my honor," I said. "I will try to keep to your wish."

"Bitte? Die papieren," the girl said, from behind me.

"Danke. Let's see what we've got," Claudette said, sitting down to look at the papers. "Here," she said. "We have a folder for Thomas Eisfelder, nothing on the others."

In the next few minutes, I learned that Thomas Eisfelder had arrived in Grantville penniless a few weeks after the Imperial army and half of the king's army had swept south on the road to Coburg last fall. His home village somewhere not far from Eisfeld had been looted and burned by one army or the other.

Eisfeld has one foot in the Saxon Dutchies of Thurungia and the other in Franconia. A Franconian jäger had shot at the power plant, so as far as I was concerned, anyone from the Werra valley was suspect. On the other hand, Thomas's story wasn't too different from those of half the Germans in Grantville.

"Ah," Claudette said, turning a page. "We helped him with job placement too. Look at the skills inventory."

I was mystified, but she translated the arcane paperwork for me. "It says he was the son of a millwright, apprenticed to his father. A good woodworker, some blacksmith skills, and good at machinery. We placed him as a carpenter with Ted Moritz first. When Mansaniello's steam engine company asked us to look for people who knew machinery, we told Eisfelder about the job."

"That's all you have?" I asked, after she started putting the papers back in order. "What about Kleinschmidt and Martel?"

She looked up at me with a serious look. "We're not the only refugee aid organization here in Grantville. Some of the churches help their own, and some people fend for themselves."

* * *

The mention of churches jogged my memory. Charles Martel was supposed to be a Huguenout. I knew that was some kind of French Protestant, but beyond that, I couldn't say much. I go to church when I can, but it's hard to keep track of all the different kinds of heretics on the fringe of the Protestant world. Some church in Grantville would probably accept the man, but which?

I set off across Grantville toward the Presbyterian Church. It's probably the poorest church in Grantville, but it's basically Calvinist, so that's where I've gone. Three men were standing outside, looking up at the building as I walked up.

"Wishing you a good morning," I said, as I recognized Pastor Wiley.

"Good morning indeed," he said. "I know your face from Sunday morning services, but I'm afraid I don't recall your name."

I introduced myself, and in turn, learned that the others were Deacon McIntire and Hans, a local stonemason. "The old building is a bit small and a bit run down," the pastor said. "We're talking about how to go about building a new church here, without closing the old one during construction."

He was modest. The old building was not merely a bit small and a bit run down. Since I'd first attended his church, the congregation had more than doubled. They talked about the new building for a few minutes, explaining that it would be made of brick and stone, and how they planned to build it around the old building. Finally, Pastor Wiley looked up at me, puzzled.

"So tell me, John, why is it you came?"

"I came to ask you a question. I've recently come across a man who is a Huguenout, and I wondered what you know about that church?"

He scratched his head. "I can't say I know much about Huguenouts, except that they're French Calvinists. I hardly knew that much when one of them showed up here back in June and asked for help. If I knew French, he could have explained more, but we had to make do with his bad English."

"So he comes to this church?"

"Yup, you've probably seen him yourself, dark hair, short, sort of a hooked nose, goes by the name of Charles. Usually sits in back. He looks like a man who could use a friend. I'll introduce you on Sunday."

"Were you able to help him?" I asked, wondering if he might be Charles Martel.

"I think so, at least, he thanked me. He said he was a locksmith, showed me a padlock, an uptime lock, mind you, and asked where he could learn how to make locks like that. I sent him to Reardon's Machine Shop, not that they make locks, but I bet they could if they wanted to."

"So Huguenouts are French Presbyterians," I said, trying to hide my recognition. A Huguenout locksmith named Charles could only be Charles Martel. I didn't want to leave the pastor thinking I was interested in him.

"Close enough," the Reverend said. "At least, more like us than Lutherans or Methodists. If your friend is ever in Grantville on a Sunday, tell him we're here and he's welcome."

"I will," I said, before I took my leave.

* * *

It was near noon, so I decided to stop at Cora's for something to eat before I went up to the police department to write up my report. All the Americans seemed to want their noon meals precisely at noon, and I'd learned that there was no point in trying to change their schedules to suit my habits.

Cora's coffee shop serves much more than just coffee. I've tried coffee made the Turkish way and made the American way, and I can't really stomach either. Cora has other drinks, though, and some really good pastries.

I was sitting at a corner table sipping mint tea and savoring a chunk of fruit cake when Cora walked over.

"Sergeant Leslie!" Cora said, smiling. Bernadette Adducci had introduced me to Cora just once, when I first started working with the Grantville police. It seems that she never forgets anyone.

"Good day, Cora," I said. "This fruit cake is excellent."

"It takes some inventing to make decent pastries when sugar is so hard to afford," she said. "I've got a German girl back in the kitchen who knows what she's doing, and between us, we've had fun."

A thought struck me. "Cora, you seem to know everything about everyone. I'm looking into three downtimers. I wonder if you've heard of any of 'em. Mind if I ask?"

"I can't guarantee results, but you're welcome to ask."

"Do you know anything of a man named Thomas Eisfelder?"

She shook her head. "Sorry, nothing."

"And how about Manfred Kleinschmidt?"

"I've had a Manfred in here," she said. "He stops in here sometimes on his way home from work. He sometimes works the night shift at the power plant, and he likes my breakfast menu."

"Sounds like the right man," I said. "What d'ye know about him?"

She grinned. "Not much, aside from the fact that he seems to be a nice guy and he's in love with a girl in Suhl. My German's not good enough yet to get the whole story. That's one hit and one miss. Who's your third man?"

"Charles Martel."

"The Frenchman?" she asked. "He works with Manfred, they've come in together a few times for breakfast, but he's also been here for dinner sometimes. He says our pastries are good, but not as good as the ones they make in Paris."

"He's from Paris?"

"That's what he says. I think something awful happened to his family there and he blames it on that Cardinal, what's his name from The Three Musketeers."

"Cardinal Richelieu?" I asked. I named the only cardinal I knew of in Paris while I wondered what he had to do with three gunmen. "Something awful? D'ye have any idea what?"

"Richelieu, right," she said, and then paused. "One morning, a pretty girl smiled at Charles, and I saw him begin to cry. He said the girl reminded him of his petite Marie, his daughter, I think. Lots of people around here have lost family, so I said she should rest in peace. He got mad at me then, swearing at the Cardinal, I think, but it was mostly in French. What I got was the word prison, that's the same in French, you know, and that it happened last May."

"My thanks to you," I said trying to string together what I'd learned.

"I got two out of three of your men. Not bad, is it?"

"Not bad at all," I said. "And a good story for one of them. I suppose now that I need to go try the pastries in Paris to see how yours compare."

She smiled at that and then turned to greet another customer while I sat there thinking. Something was wrong, but I couldn't put my finger on it.

* * *

The pieces began to fall in place after lunch when I stopped into the police station to report on my morning's work. Much as I dreaded writing the reports the Grantville police demanded, that was what forced me to put all the facts I'd learned into order.

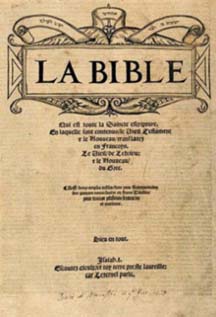

There were more facts on hand as well. Deloris Francisco had been on the evening shift the night before, and she'd phoned the landlords of our three suspects and written up a report on them. She'd learned that Thomas Eisfelder had come to Grantville simmering with anger at all soldiers for what they'd done to his home. The time he'd been arrested, it was for attacking a soldier. She'd learned that Manfred Kleinschmidt liked to carve wooden toys in his spare time, and she'd learned that Charles Martel had a great big Bible, all in French, that he read in his spare time.

Jill had a date for Martel's arrival in Grantville, the fifth day of June. That was in good agreement with what Pastor Wiley had told me, and it was as I was thinking about the dates that I realized what was wrong.

"Angela," I asked, looking up from my hastily scrawled notes. "How far is Paris from Grantville?"

"I don't know," she said. "Does it matter? I can phone the library and ask?"

"Please do that," I said.

A few minutes later, she had the answer. "It's about 500 miles by road."

"Call the power plant," I said. "I want to speak to Scott Hilton."

"What's it about?" she asked, dialing the phone.

"I think we need to arrest Charles Martel," I said, as she handed me the phone.

"Chief!" she called, while the phone was still ringing.

* * *

As things worked out, we didn't get out to the power plant until late afternoon, but Scott had told me that Martel was working the evening shift. I had ample time to explain everything to the chief and it gave the chief time to arrange backup. The Grantville police rule is to bring backup, as they call it, when you set out to arrest someone.

So it was that I set out for the power plant with Jurgen Neubert and Rick McCabe. Rick would have been enough, but Chief Frost wanted Jurgen along for the experience. By the time the evening shift began to arrive, we were all hidden away. Scott and I were in an upper room he called the steam project office, a room cluttered with drawings and books, while I had Rick and Jurgen waiting behind a closed door across the hallway.

The guard at the gate phoned us when Martel checked in, and then Scott gave him ten minutes before phoning the machine shop and asking for Martel. Two minutes later, the Frenchman came into the office.

"Charles Martel?" I asked. He was a small man, dark haired and thin.

"Monsieur?" he asked, looking puzzled at the sight of me.

"You left Paris in May, and you arrived in Grantville on or before the fifth day in June. Why would a Paris locksmith be in such a hurry to come to Grantville?"

Charles gave a weak smile. "Ah, c'est comme sa.Un, a man in Paris give me un cadinas, a lock. Il a dit, he say it is from here. I am un maître serrurier, quel est le mot, master locksmith? I never see such a lock before, so I come to here."

"How did a lock from Grantville come all the way to Paris and to you?"

"Je ne sais pas," Charles said. "A man, he come and he give it for me. Il a dit, if you want learn this thing, go to Grantville."

"So you came five hundred miles in less than thirty days. I'll bet you didn't travel on the Lord's day, so you came at least twenty miles a day. You didn't carry that great big Bible of yours on your back, who paid for the horses? Surely a locksmith can't afford to abandon his family to run halfway across Europe."

The look on his face shifted from confidence to fear, but he said nothing. I glanced to the doorway, checking to see if Rick and Jurgen were in place.

"And your family, why did Cardinal Richelieu throw them in prison? Did he do it to force you into his service? Did he pay for the horses? What did he ask you to do when you got here?"

"Cardinal Richelieu," he said, and then spat. "Il est un diable. He did say that I only need make the petites choses to save my woman and my girl."

"Just little things," I repeated. "Like telling that Franconian jäger where to shoot?"

"Je ne sai pas who did shoot on the insulators. I just send a letter expliquant les insulators."

Scott Hilton had kept his silence, but now he spoke. "You almost killed Franz Schneider!"

"I not want to make bad to anyone," he said, with a sigh, letting his head drop. "Tout est perdu," he added, and then exploded out the door.

As I turned to follow, Rick was on the floor holding his gut where Charles had butted him. Jurgen disappeared down the steps at the end of the hall as I passed Rick. I joined in the chase, and the next minute was crazy. Charles Martel may have been a small man, but he was fast.

As I came out into the hall where the new steam engines were being built, Martel was halfway up a ladder to an overhead walkway. A siren sounded as Jurgen started up the ladder. "Attention, achtung, stop, halt." It was Scott's voice coming through a speaking machine so it was louder than life.

I started for the ladder, but Jurgen was already there, so I stopped. Martel would have to come down somewhere if he was to get out of the building. It seemed that the best thing to do was to follow him from below.

The catwalk along the top of the hall rang as Martel ran, and then he started across the bridge that spanned the hall to hold up the crane. There was a little cabin on the bridge right above the hook, and before Jurgen was halfway to the bridge, Martel was in the cabin and the bridge was moving. It did not move quickly, but it moved toward Jurgen fast enough that Jurgen retreated to the safety of the ladder as the bridge came at him. At the same time, the cabin and the great hook moved away from the catwalk and the hook began to drop.

A woman's voice rang out through the speaking machine. "Someone kill the six-hundred-volt power," she said. The moving crane drifted to a stop, with the hook swinging ponderously below it, coming close to the spinning flywheel of the new engine with each swing. Jurgen warily climbed back onto the catwalk and began edging toward the crane as Scott and Rick came out beside me.

"That was close," Scott said, as we stood watching the crane.

"What?" I asked.

"If he'd kept going, lowering the hook and coming this way, he could have hit Unit 6. If he'd hooked the flywheel while it was running, he could have wrecked the crane and the engine. Good thing Nissa noticed the threat and killed the motor generator set."

"How'd he know how to work the crane?" Rick asked, as Jurgen stepped onto the catwalk that led along the beam toward the crane cabin.

"We do a lot of cross training," Scott said. "We don't want to be stuck with just one person who can . . ."

He fell silent as Martel bolted from the little cabin above the hook, making for the opposite end of the bridge from Jurgen. There was no catwalk at that end, just a narrow ledge along the south wall of the building. As Martel walked along the ledge, he was sharply outlined against the windows behind him.

"He'll not get down from there easily," I said.

Scott scanned the wall. "See that loop of chain at the east end? It works the windows, he could shinny down." He ran for the bottom of the chain just as Martel began pulling up on it.

The chain rose up out of reach just before Scott got there. As Martel pulled the chain, it turned a wheel at the top. The wheel turned a shaft that pulled the tops of the windows inward while their bottoms opened out. I didn't understand what was happening at first, but Martel was letting the chain out the window behind him.

"Va au diable, vous tous!" Martel called, as he began backing out the window.

I turned to run for the outside door, but that was at the west end of the hall, and Martel was escaping to the east. Rick and I made it to the door together, and he beat me around the corner of the building to the south. A row of great wooden boxes separated the plant from the Buffalo Creek, with clouds of fog rising from three of them accompanied by a sound like a waterfall. I came around the corner of the building just in time to see Martel jump to the ground and flee toward the creek between two of the boxes.

Scott Hilton came around the east corner of the plant running toward us, and as we met, Jurgen's head appeared in the open window above. The three of us on the ground followed Martel between the great boxes, but when we arrived at the creek, it wasn't obvious which way to go. The creek was shallow, Martel could have crossed it, but he could just as easily have gone upstream or down.

We split up, but there were too many places to hide and it was already getting dark in the shade of the ring wall, although the sky was still bright. We never did find Martel, even after we went back inside and organized every man the plant could spare for a search. I learned that the giant boxes were cooling towers, even though they weren't towers. I learned that the coal pile had a faint sulfur smell when you walked around it, and I learned that the fence around the power plant was over a mile long. Officially, the fence had only three gates, the main gate, the railroad gate at the east end, and the old railroad gate at the west end, by the refugee camp, but there were also gaps in the fence where the creek flowed through.

My guess is that Martel got away after dark and fled the Ring of Fire. How he got out of the plant, we may never know. The gates were all locked or guarded, but he could have waded out along the creek, and the railroad gate was opened every time the railroad brought in another load of coal from the mine.

* * *

When I got back to the police station, Chief Frost was still there, and he was furious. He knew what had happened, Scott had telephoned from the plant. "Damn it, Sergeant Leslie, you should have just slapped the cuffs on him and brought him in. No need to try for a parlor scene like in an Agatha Christie story. And you should never have let Jurgen go climbing around on that gantry crane! He could have fallen. Leave that kind of monkey business to the folks at the plant."

He paused. "One more thing. Scott Hilton said Martel had been working on making poppet valves for those new steam engines. He said the threads on the inside of the nuts that hold the valve heads to the valve stems were almost drilled out, so the nuts would be likely to pop off inside the engine."

The next morning, I got to see Martel's Bible. The police got a warrant to search Martel's lodgings, and they found very little aside from an Olivétan Bible and a Master padlock. A French Calvinist would treasure that Bible, but it wasn't a Bible a man would want to carry on a long trip, nor was it a Bible a tradesman would be likely to own. The Bible showed signs of ample use, with many passages underlined. Chief Frost guessed that the underlined words and passages might be part of a code, but I've seen serious students of the Bible mark bits of the text like that. We may never know the truth about that book.

Colonel MacKay showed up while I was looking at the Bible. He started in on me as soon as he saw me, but Chief Frost stopped him. "Colonel, I already chewed him out. You're not saying anything I didn't already say, and I've had a good night's sleep since then. I think we did pretty well, considering. It sounds like this Martel fellow admitted what he did. I doubt he'll come back. The question is, are there other saboteurs in among us? There was that derailment last month, was it an accident? And what do we do if someone like Martel is working at the coal mine?"

* * *