Heskil Brant pressed the security plate. Inside, the bridge lights came on, and the door slid open with a faint hiss. She went in, limped to the contoured captain's chair, and heavily, tiredly, lowered herself onto it. The wrap-around window she left opaqued, its default state; she wanted the sense of solitude—had earned it these past days.

The door she left open, the last valve in a series that would let in outside air.

Brant hadn't always been captain, or even a licensed officer. She'd hired on the WS Adanik Larvest as G-4 Life Support Technician (biologist), and for that final trip, acting supercargo. That had been long ago. For the last eight years she'd been the ranking survivor. And throughout their twenty-nine years stranded here, she'd been one of the most important, because like small cargo ships in general, the Larvest carried no physician. In the merchant service, biologists were cross-trained to treat the ill and injured.

With the computerized clinic, that treatment would ordinarily have been entirely adequate; on the rare occasions when it wasn't, you could put the patient in a stasis chamber till you got to port somewhere, to a doctor. But here, unknown viruses and bacteria had adapted to the crew, over the years, and the clinic wasn't programmed for unknown diseases. The best it could do, with her help, was treat the symptoms and ease the discomfort, which by itself had repeatedly saved lives. The stasis equipment hadn't been used because they weren't going anywhere—this was the end of the road—and the engineer had been against using the backup power system to run it.

Thus she'd presided over too many deaths, including four of the six children she herself had borne on this world, and two of her four grandchildren. But she was tough. Only the tough—a few of the tough—were still alive.

She touched the key that powered the vocator, and spoke instructions to the computer, then sat silent for a moment, gathering her thoughts. Since Captain Terlenter had died, two others had been captain, but neither had extended Terlenter's side project: He'd dictated a brief history, or most of one, of the sector of space they'd come from. For the generations to come, who would know only this world, who would never even know anyone that remembered. Then the great puking fever had visited, and Terlenter had been the first adult to die. Briskom and Walter hadn't followed through on it. There was always so much else to do, more immediate, more survival-oriented. And writing, even by vocator, was a difficult—an unnatural—activity for some. For many. It was as if they retained no subroutine for it; had to program it anew each time.

Terlenter had gotten as far as the beginning of their own voyage. It had started innocuously enough—a small cargo ship with a crew of nine men and six women, and a cargo of 600 pleasure droids in stasis. Then the war had begun, the sector-wide megawar that everyone had feared and been telling each other could never happen. A war with planet busters. So Terlenter had sent them hurtling outward. That much was already on "paper."

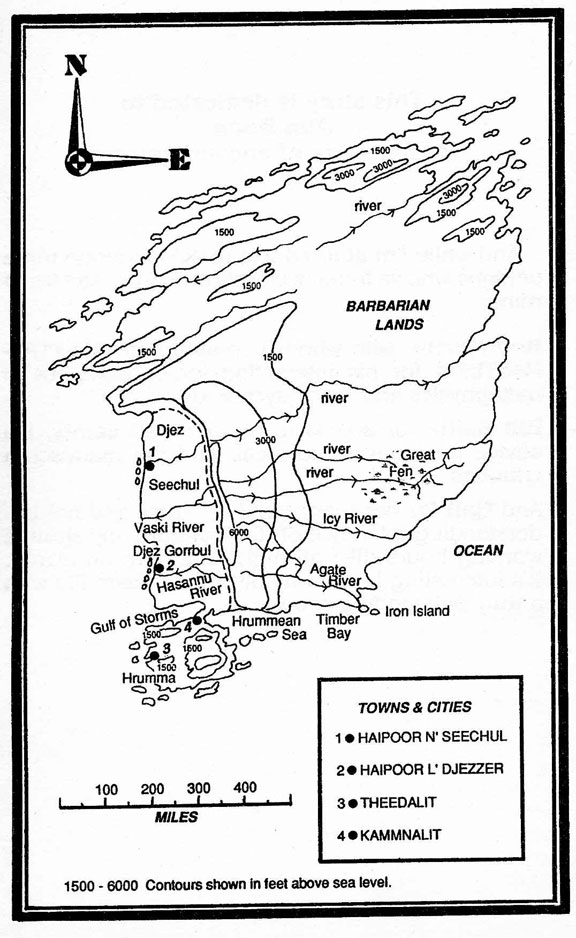

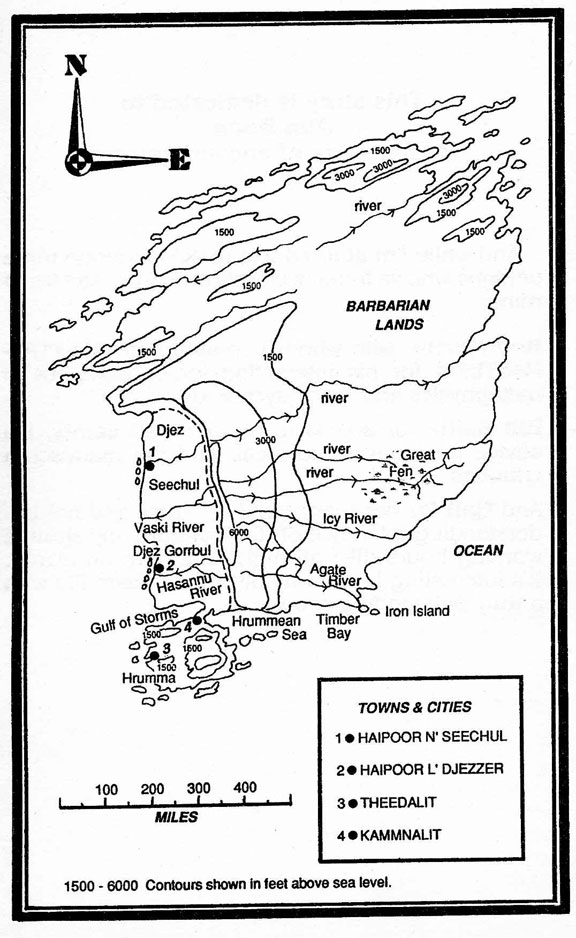

Heskil had taken the story from there, reciting slowly and reflectively to the computer, which extruded a slow succession of printed sheets as she talked. The Adanik Larvest hadn't stopped fleeing till they were well outside human-occupied space. Then, as they hunted for a new home, a patrol had challenged them, three tall, asymmetric ships like neo-baroque sculptures of scrap metal, rods, and wire. The holo plate had shown beings horned and leathery, who'd called themselves something like "Garth." Quickly enough, their computers had learned to talk with each other, and the garths had ordered the humans to leave their sector, then gave them boundary coordinates and let them continue.

Outside garthid space, this had been only the third system they'd explored—a type-G bachelor sun with twelve planets, not an uncommon assemblage. One of the planets had displayed habitable parameters in terms of gravity, mass, and solar constant. Optically they could see blue ocean, white clouds, thirteen percent land surface . . .. Probes told them the chemistry was right, including the biochemistry, as mankind had learned to expect of worlds where the physics was right.

From there, she'd told how they'd selected a homesite, on the major island of a large archipelago where the life forms suggested there'd be little or no predator trouble. How they'd unloaded the droids on a continent a third of a planetary circumference away because they'd had no way to program them, then returned to the selected colony site. And how the matric tap had blown on landing, leaving them with only the emergency power system. That had been enough to power the computer, and some ship's accessories including the clinic and lab, but not the complete life support system. They were lucky the local fauna was edible and initially trusting.

The last time she'd dictated, she'd started on the history of the colony itself. They'd named it Almeon, after a mythical island. It would have been a happier history if they'd been trained and equipped for colonization. Instead it had been a matter of cope, struggle, and innovate. The standard ship's library tank, so often ridiculed by spacemen, had proven a lifesaver.

And they, from a planet that had long controlled birth privileges, had reinstituted an ancient imperative: "Be fruitful and multiply!" But their gene pool, tiny to start with, had shrunk from illness and accident. Thus rigid breeding rules had been laid down and enforced, to restrict as much as possible the homozygosity of any lethal and sublethal genes.

Today she continued the history with the first birth on the new world, took it through the first plague, then went on to the first successful forging of local iron, while the silent printer filled sheets with her words, depositing them on the stack in the receiver.

While she'd dictated, her aging muscles had grown tight and sore, and getting up from the seat, she rotated her shoulders to loosen them. It occurred to her then that there was only one copy of the history. True it was nonflammable, the paper-like material extremely durable, the printing integral within it. But she decided that before she left that day, she'd instruct the computer to produce additional copies of the story, one for each family in the colony.

Already the children, and to a degree the adults born on this world, lacked a strong sense of their roots. Even within sight of the 285-foot hull-metal cylinder of the Larvest, the problems of primitive colonization coerced the attention, capturing and narrowing one's sense of what was real and important. Even, mostly, her own. It was time for the handful of surviving crew, those whose eyes were still good enough, to start reading the history aloud to the children and grandchildren. Or the native-born adults could read them, those who read well enough, and the elders could explain, clarify, elaborate.

Then, as she was sitting back down, the wall luminosity went out. The codes disappeared from the suddenly unseeable computer screen—and the door hissed shut behind her. She knew instantly what had happened, felt her skin crawl cold and pebbly, and got up again, groping her way through the utter dark toward the bulkhead and doors behind her.

The doors would not budge, and for a moment bile rose in her throat. She fought it down. They'd assumed that someday the emergency power would fail, perhaps in a century or so when the fuel slug was exhausted, perhaps sooner when some other element in the system failed. But it had never occurred to her that the doors, this door, were held open by some mechanism and would close if the power went off.

Again she groped in blackness, looking for something to pry with. All she found was a stylus at the command console, and tried futilely to insert it in the thread-thin space between the doors. That failing, somehow the incipient panic died, leaving her mind clearer than it had been for decades, perhaps ever. She conjured in it the layout of the bridge, looking for a way out—something, anything. If only she had light! She felt for the rocker switch that so many times before had de-opaqued the windows, but when she pressed it, nothing happened.

There should, it seemed to her, be a way out of the ship, a manual override. Otherwise, a ship without power in space couldn't even open its lifeboat ports. But she was no engineer—they hadn't had one for eight years—and nothing came to her.

Still, she would miss no bets. Idly she felt over keypads, knowing from memory what most of the keys did, had done. Now they did nothing. The console was lifeless. Dead. The whole ship was dead. And if there was a way out of the corpse, she didn't know of it.

In her mind she computed the approximate air volume of the bridge, allowing for equipment, multiplying by twenty-four percent to get the oxygen content. But she couldn't take her computations further because she didn't know the rate her breathing would remove it. She supposed she had an hour or more. Perhaps several.

Mentally she shrugged. She'd lived sixty-four standard years. On this world, that was old. And it would be an easier death than most. Easier than her husband's had been, her children's. It was time, she told herself, for a well-deserved rest.

A little later it occurred to her to wonder if, in a millenium or ten, one of their descendants would reinvent the electric generator. And if, sometime after that, someone would couple a cable to an external service jack, open the ship and find "the book." It seemed almost bound to happen, in time, if the colony survived.

What would she look like then? A skeleton, its fat flesh long gone. More important, what would they look like then? With a gene pool no larger than theirs, there'd be genetic drift. Would they still know Interspeak? Hardly. Their language would evolve. But if they retained writing, it might not change too much for the book to be deciphered.

Meanwhile they'd get along without knowing their cultural roots, their history. They'd grow, setting new roots wide and deep. It was what this planet required of them.

She reclined her chair a bit—interesting that that was manually controlled—and let her eyes close, let her thoughts idle, almost as if rehearsing death. After a little while she went to sleep, perhaps to work out old dreams.