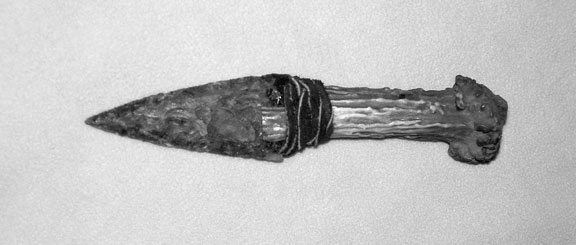

[Photo by Charlotte Proctor of a flint knife made by Greg Phillips;

from the collection of Laura Brayman.]

It wasn't until the invention of bronze that the sword became possible. Before that time, knives, axes, spears, and even clubs were multi-purpose, used as both tool and weapon. But with bronze, an alloy of tin and copper, an item that was purely a weapon became possible. It is easy to postulate, but not prove, that with the invention of the sword a pure warrior class became possible. Bronze was expensive, and only a few individuals could afford swords, but this gave them an unquestioned advantage over opponents armed with flint knives and axes.

[Photo by Charlotte Proctor of a flint knife made by Greg Phillips;

from the collection of Laura Brayman.]

It is probable that the invention of bronze was first achieved by copper-using people, and in many cases fully developed bronze weapons were introduced into Stone-Age cultures. In Northern Europe there are flint daggers and flint "swords" that appear to be copies of bronze weapons. In Denmark there is a polished stone axe head that is an excellent copy of a bronze axe. The flint knapping is excellent and appears to be a brave but futile attempt to stay up with the new metal. It's rather like developing a truly superb carriage about the time the automobile came along.

The estimated time frame for the development and use of metals is constantly undergoing revisions backward. Until recently, the discovery and use of copper was thought to have occurred about four thousand years ago. However, several fascinating new discoveries have pushed the time frame back at least a thousand years, and raised even more interesting questions. One of these discoveries was the body of a man preserved in ice. I will digress a bit to tell his story, to show a little of the cultural context in which these early weapons were used, before I get to more technical matters.

OTZI

The Otzal Alps lie between Austria and Italy. They are partially covered with glacial ice so that only small sections ever melt. In 1991, two hikers discovered a man's body. At first the authorities were uncertain as to how old the body was, but when scientists were able to examine the corpse, it was found to be about 5,300 years old! The body was in a remarkable state of preservation. But what was even more remarkable, and thrilling, was that his tools and clothing were found with him.

The individual, who has been nicknamed Otzi, had bearskin-soled shoes that were stuffed with grass, fur leggings, a fur jacket, a grass overcape and a fur hat with ear flaps. All of the clothing was well made and highly serviceable. In addition, he also carried some fire-making tools, some fungi that was probably used as a medicine, and some berries to eat. His equipment consisted of a double-edged stone knife that was hafted with wood, a bow that was only partially finished, twelve blank arrow shafts, two arrows that were broken, and, most amazing of all, a copper axe.

The copper axe was quite well made, with an edge width of about two inches. It was attached to a shaft two feet long. The length of the shaft suggests to me that the axe was primarily a weapon, as tools usually have a shorter shaft. Chemical tests on the body also indicate that Otzi himself was the likely candidate for having cast the axe, as his body contained chemicals that are produced during the casting process.

But let me digress here to tell a bit more of Otzi's story, because it's fascinating. He not only deserves a book about him, but should get a novel as well.

Otzi was between 25 and 45 years old, about 5 feet 4 inches in height, and weighed about 150 pounds. Speculation was that he had been caught in a sudden storm and had frozen to death. The body and equipment were studied a great deal, but it was close to ten years before someone thought to put the body through an imaging scanner. When they did, the scientists received quite a shock. Otzi had not died of natural causes or under accidental circumstances. Otzi had been murdered.

Under his left shoulder blade was a stone arrowhead. The arrow had passed through the left arm, cutting through the triceps, probably some nerves, and had penetrated the body, probably the lung, although I am not certain of this. Medical opinion is that he would have died from the wound in about two to four hours. Once the arrowhead was located, an even more thorough search of his body was made and turned up some more wounds. These wounds were on the hands, and are what are generally referred to as "defensive wounds." When someone is attacked with an edged weapon they will usually attempt to fend off the attack with their hands. This results in many deep gashes in the hands and rarely results in stopping the attack.

We have an individual with a valuable axe, a half-finished bow, and a quiver with twelve unfinished arrows and two broken arrows, and an unsolved murder. It's impossible for me not to speculate on the tale of Otzi.

A hostile encounter leaves Otzi with his bow broken. He would retrieve the two arrows, broken in the fight, as the heads would be useful later. He finds some wood suitable for a bow and begins to prepare it. He does make some arrows, but does not have time to finish them. He is again attacked. This time the fight is probably hand-to-hand, and Otzi again makes his escape. But as he's fleeing uphill, an arrow finds him. Although mortally wounded, he keeps on, probably losing his pursuers, maybe in the dark, or because a storm came up, or just because of the cold of the mountain. He falls, only to be found 5,300 years later.

Interesting. One of oldest mummies found in Europe, and he was murdered, or, if you like, killed in battle. For Otzi didn't die quietly without a struggle. Subsequent tests revealed blood samples from at least three individuals on Otzi, his clothes and his weapons. We don't know if he was the good guy or the bad guy, what we do know is that it is a fascinating development.

While everything about Otzi is fascinating to us for what it can tell about a time that is mostly unknown to modern civilization, from the parasites in his intestines, to his wounds, clothing and tattoos, I am most concerned with that copper axe. This indicates that copper was much more in use than had been previously known, and that the earliest use dates back much further than had been stipulated before his discovery.

To further substantiate this, there was a recent discovery in Jordan of a copper weapon and tool producing factory. The factory is about five thousand years old, and in many respects this is a more important find than Otzi, though less viscerally exciting.

THE MANUFACTURE OF COPPER

At the end of the 20th century, an amazing discovery was made at an excavation in the desert of southern Jordan. Located not far from the Dead Sea, Khibat Hamri Ifdan was a massive metal working complex. Although the site was found in the l970s it was not fully excavated until 1999. The findings have been most impressive.

Archeologists uncovered a factory that was dedicated to producing copper tools; axes, hammers, knives and other items, including copper ingots. This operation was not a small four- or five-man job shop, but was quite large, obviously a factory. The factory contained about seventy rooms and, at the last counting I have heard about, the team had uncovered hundreds of ceramic molds, broken and discarded items, and approximately 5,000 tons of slag. This much slag indicates that the plant must have produced hundreds of tons over its lifetime.

It also appears, and is reported, that although the plant produced many tools and items, the primary operation was the making of copper ingots. This indicates a rather large trading network, as locals could not use as much copper as was produced. The plant was destroyed about 2700 BC by an earthquake. This time frame is right at the beginning of the Bronze Age. Frankly, I don't think anyone expected to find such a large operation at this period in time. Prior to this, the largest operation known was in Hissarlik, Turkey (believed to be the Troy of legend), and Hissarlik produced only about 70–80 items. An operation of this size indicates that the production of copper had been known long before had previously been believed. You simply do not organize a large operation such as this unless you have the artisans, the knowledge, and the market for the items that you will produce.

It is doubtful that swords were ever produced in copper. A few may have been tried, but abandoned once they were found unserviceable. Copper is simply too soft to make a good sword. Knives and axes and hammers, yes. Still, it is easy to see the antecedents of sword-making factories here.

In order to produce so much copper, it is necessary to have several different occupations come together: mining, mold making, wooden pattern making, charcoal manufacturing, heating and smelting—not to mention the trade routes that must be established and serviced. What an exciting time that must have been for the adventurers who took up trading! The world was a huge place back then. I am sure that many traders never ventured too far afield, but I am also sure that the more enterprising and adventurous sort spent years in travel, even unto the Cold Northern Seas. Which brings us back to bronze, and the true beginning of the age of swords.

We know the process for producing an item of copper or bronze. First a master is made. This can be of wood or clay. Once this is made, a mold is made that will separate and allow the master to be removed. The mold can be of clay, stone or even ceramics. It is possible, and it was done, to make a master of wax, and then burn it out, but this was later once the casting was well established. It is doubtful that this was done for simple tools, though, as it would be too expensive.

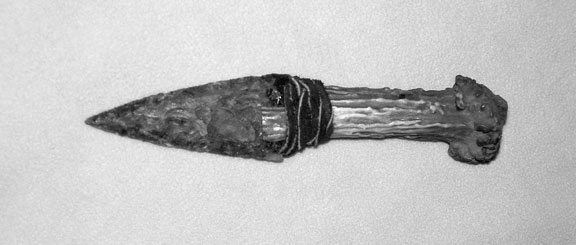

[Drawing of a mold for a copper sword.]

The mold is filled with molton copper or bronze, and once it has cooled, the mold is separated. Another method, almost as common, was simply to carve the mold out of stone. This was practical for flat type axes and other items that were one sided. Of course you can make a left and right side of stone, and have a more durable mold, but this would seem to be more expensive than merely using a ceramic material.

Very early copper working may have been done by just one or two people. But it quickly becomes evident that superior items can be produced at a faster rate by several people working in sequence. You need someone to dig the ore, someone to smelt it, a master maker to carve or mold the master, someone to make the molds, someone to cast and pour the metal. You will also need someone to gather the wood for the fire. The culture was much different then. You couldn't call up and order coal, or turn on the electric furnace. In short, this was a cooperative venture involving a large number of people, and remained that way even until modern times. The casual solo blacksmith who took iron ore and forged a blade, ground it to shape, filed, sharpened and polished, then made a hilt, balanced it, and also made a scabbard, is so much romantic nonsense. Oh, I wouldn't say that it never happened; it is quite possible that a few tried it that way. Certainly legends tell of this happening, and always a very special sword is produced. But there were romantics back then, too, and since the sword was venerated in most societies, special blades were even more desired and sought after. But it really didn't work. Today you have some superb sword and knife makers who do each part of the whole process, but today's swords are art items, and not utility pieces. But I digress; we are still talking about copper and bronze.

Knives, axes, spears and clubs can all be made from copper. And all can be capable weapons, just not good ones. But the same is not true of swords. Copper simply does not have the strength to support a long blade. However, with the addition of about ten percent tin to the mixture, it becomes a very tough material, of surprising strength and durability.

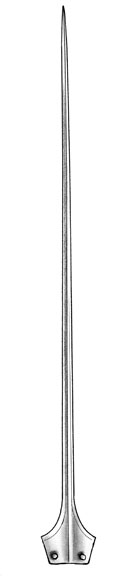

[FIGURE: Photo of a reproduction bronze dagger

from the collection of Hank Reinhardt, #175.]

Bronze weapons soon began to dominate the battlefields of the world. The spread of bronze is the cause of much speculation, and is likely to remain more speculation than fact. Was it because of trade, war, or simply spontaneous development in many different places? We simply do not know how the knowledge of bronze working was spread. What we do know is that there was a surprising amount of trade between the Mediterranean and England and Ireland and even China at that time.

THE BRONZE AGE

The invention of bronze was a significant event in the history of man. With bronze, man was at last able to develop a tool that was pure weapon: the sword! Compared to flint, obsidian and copper, bronze was really a magical material. Bronze is hard enough to take a sharp edge, and yet not become brittle, and it was quickly made into that familiar shape we call a sword.

It would be interesting to create a neat chart of the development of the sword, but while a great deal is known, not enough is known to be able to state that bronze was developed in a specific area, and spread in such a way. It appears to be an invention that occurred within a few hundred years around 2000 BC in the Middle East as well as China.

As far as I have been able to determine, there does not seem to be a "national" or "ethnic" grouping to these swords. One is as likely to show up in Turkey as in Ireland. Let me also add that I have handled many more steel weapons than bronze ones, and I am aware that my knowledge of bronze weapons is limited.

Bronze spread throughout the Middle East, and then into Europe. Mercantile trading must have been quite an adventure back then, taking bronze tools and weapons into Europe to trade for amber and raw materials. The traders who followed the rivers into Northern Europe were probably a tough, hardy lot, and well able to defend their wares. The dangers of sea and forest were not undertaken lightly four thousand years ago.

The merchants traveled the Mediterranean to Iberia, maybe into the vast Atlantic and the frozen seas to the north, England, or the Scandinavian countries. All with storm and shipwreck and pirates a constant threat, and not even knowing how they would be received when they got there. Or maybe they took the land route through what we call the Balkans into what is now Germany, trading ingots of bronze or even weapons for tin and amber and furs. They faced unknown tribes, and could never be sure if they were saying the right thing or insulting the chief beyond all recall.

Could you trade with this new tribe, or would they attack and try to take your goods? You would never know until the transaction was finished. Wild lands, wild animals, and even wilder men: facing these required toughness, cunning and determination. One thing is for certain. It could not have been a dull life.

Not only were items made of bronze spread throughout Europe, but the knowledge of how these items were made was also disseminated. Soon there were bronze manufacturing centers all through Europe. This spread of information and goods was not done overnight. Indeed, it took several hundred years at least. For many years stone and bronze existed side by side. As mentioned earlier, there are several examples of stone daggers that are copies of bronze daggers, and flint swords as well. This is both pathetic and heroic.

MANUFACTURING IN BRONZE

Just like manufacturing in copper, manufacturing in bronze is not a simple procedure and requires more than one or two men. It also requires the extra step of alloying the tin and the copper. A bronze sword must be cast. It cannot be forged like iron. In order to make a sword, one must have the required amount of bronze, a good furnace in which to melt it, and molds in which to pour it. First a pattern must be made. This was probably done in wood, although I do not know of extant archeological remnants that would verify this. After the pattern was completed, a mold was made. This was done in clay, with a coarse clay on the bottom, and a much finer clay on the top. The pattern was then impressed into the clay and another mold for the top was made. After the molds were completed, they were then baked until it was dry and hard. (Dry was very important: molten bronze poured on water could have an interesting effect on those standing around.*) Gates were provided so that gasses could escape, and the sword was cast.

After the sword cooled, the mold was broken and the sword taken out and finished. The blade edges were hammered thoroughly. The hammering was very necessary, as this work added about twenty percent to the hardness of the edge. The sword was then polished and decorated.

Without a doubt the manufacturing process was quickly streamlined. We can see this from the recent excavations in Jordan. This was not a small operation, as it had sections devoted to certain tasks. This is practical and economical. There is a tendency today to think that our ancestors were not nearly as bright as we are. This is nonsense. They did not have the amount of knowledge available that we do, but for sheer IQ and ingenuity they were easily our equals.

In the manufacture of items with a specific usage, you are limited by the material being used. All swords can be broken down into swords used for cutting, for thrusting, and for both cutting and thrusting. You can't make a practical sword out of rock, bone, wood or glass. Rock and bone are too brittle, wood too dull and glass too fragile. Bronze, on the other hand, can make a pretty decent sword. It is easily seen that a sword designed for a single purpose will do it better than one that attempts to do both. Bronze Age weapons are no exception to this rule.

Weight can be a problem, as bronze is almost one-third heavier than iron. While bronze is heavy, it is also attractive. Many Bronze Age swords are as elegantly beautiful in shape and design as anything ever produced in steel. They have the additional advantage that the metal itself, when properly polished, is strikingly beautiful.

In today's world we are used to brass, a copper-zinc alloy, and encounter bronze only rarely, and never in swords. This can easily lead to a misunderstanding of the bronze swords in their design and use. Because bronze is heavier than iron, and because it is also softer, it requires more metal to give it strength, and this makes it even heavier. This leads to a certain similarity in the forms of all bronze swords, even from widely separated areas. It seems likely that this was due to several things: dispersion of both knowledge of manufacture and the weapons themselves, plus the fact that the designs are quite effective.

There is one exception to this statement: early Egyptian and Assyrian swords are quite different, but both show a mutual influence. There are many illustrations of Egyptian swords, and one or two originals, that show swords that are a long triangle in shape, and are cut and thrust weapons. These are, in both form and function, almost identical to many swords shown on Assyrian bas-reliefs. But one Egyptian sword, the kopesh, is believed to be the ancestor of the Greek kopis, and subsequently the falcata and then the kukri. Now, the kopesh is sickle-shaped, but in the few that I have seen, the edge is on the outside of the curve in some of the swords, and on the inside in others. (On the kukri and falcata, the edge is always on the inside, and the lineage attributing the kopesh as their ancestor may simply be apocryphal.) When the edge is on the outside of the curve, it bears a great deal of resemblance to some Assyrian and Sumerian swords that have been excavated. In Abyssinia a sword that was in use until quite recently is the shotel. This is a highly curved sword that is usually sharpened on the inside, but many, including one in my possession is sharpened on both edges.

[Photo of shotel from the collection of Hank Reinhardt.]

Although we cannot know for sure, it seems reasonable to assume that it is a descendent of the kopesh.

There has not been an in-depth study of Chinese bronze weapons. I feel that this has been due to political climates and proximity rather than a lack of interest. The few Chinese weapons that I have been able to see, both in photographs and in person, are quite attractive, well made, yet with a definite touch of the exotic about them. I would dearly love to see a good study made of all of them, and not just the sword.

THE SHAPE OF THE BRONZE SWORD

Bronze Age swords did show some variation because they varied in their use. There were cut-and-thrust swords, short cut-and-thrust weapons, rapiers, and long slashing weapons. But due to the limitations of the material the weapons were heavier, thicker, and slower than comparable ones made of iron. Nevertheless, they were still effective enough to kill people.

The classic Bronze Age rapier is found from Ireland to Greece and from Denmark to Italy. We do know that there were extensive trading networks linking Europe with the Middle East, so it is impossible to tell from whence the sword originated. However, we also know that many were made in separate locations such as Ireland and Crete, as we have archeological evidence of this. There is a sword found in Lissane, Ireland, dated between 1500–1000 BC, that is almost completely identical to a Cretan rapier of a slightly earlier date. It is not only the rapiers that are similar, but the cutting swords as well. From the accompanying drawings you can see the great similarities of these swords, although they come from different parts of the world.

[Drawings of the Lissane sword and Cretan rapier.]

Most of these weapons were rather long, with blades of more than thirty inches. All of the thrusting swords have thick and rigid blades. The thickness gives them great power in a thrust. It is doubtful that they were used in what we would consider "fencing"; the sword is simply too heavy. Although a blow from one of these might be as severe as a blow from a mace or club, undoubtedly the blade would bend. But I do believe that a style of fighting did evolve around this type of sword. I have no proof of this, just a strong hunch. Possibly they were used with the right hand on the grip, and the left hand on the blade, such as you might use a short spear. Certainly the thickness and the weight of the sword would give them enough power to penetrate most armor of the period.

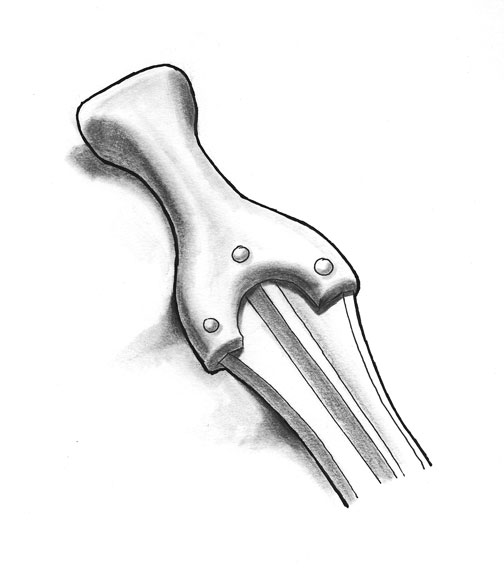

It is generally believed that these weapons were the first true swords, and that they developed from the knife. There is a lot of evidence is support of this. There are many bronze knives that have been sharpened to such an extent that they no longer resemble knives, but rather stilettos. It does not take much imagination to see a bronze knife maker looking at one of these, and thinking about making a longer knife. Since these are weapons, it is obvious that a much longer blade would be better in combat than a short one. To strengthen the case even more, grips are attached in such a way as to make it impossible to use the sword in any cutting actions. Some of the early rapiers have the handles fixed by a rather odd method. The grip is a separate piece, and is fastened to the sword blades by rivets. The butt of the sword blade is curved, and the handle riveted over it.

[Drawing by of a riveted handle.]

This grip is weak, and this is why I began to wonder if they may not have been used with two hands. The grip attachment is so weak that if a thrust was made and hit slightly off center, it could cause the grip to break. Again, pure speculation on my part, with no evidence except my own playing around to support it.

While this kind of riveted handle is not very strong, as long as the user's force is directed forward in a thrust, it is sufficient. The moment you tried to cut with it, though, or should the blade be struck hard from the side, the rivets would start popping and the blade come loose and fall off. This leaves one with only the grip. Not only is this disconcerting and dangerous, it also plays holy hell with the Heroic Image that we warriors like to cultivate.

The majority of the extant swords with this construction show damage, and are oft times missing their grips. As a result, this particular method of attaching the hilt was discarded, and two other methods were used, both of which worked very well. One was to draw the blade out into a tang, and attach the grip to this. This method was a forerunner of the way sword grips were attached in the Middle Ages, and how most modern functional reproductions are produced. Although superior to the first method, it was still not as optimal as it could be. While this method works very well in steel, bronze is not strong enough and it often broke. Again, I'm sure this was rather disconcerting to the warrior in the middle of a vicious fight. I can imagine what it would be like to land a blow, swing your sword aloft for a killing strike, only to have the blade fly away like someone who owes you money!

Cutting swords appear to have arrived slightly later than the rapier, but again, this is something that we can only speculate about. Certainly the cutting swords have a much stronger grip. With the development of the improved grip, we now encounter what we can call the typical Bronze Age sword. This is a leaf shaped blade with a narrow waist, swelling to a very effective cutting section, and then tapering to a deadly point.

[Photo of reproduction leaf-shaped blade

from the collection of Hank Reinhardt.]

This is one of the most beautiful of shapes, and is also quite effective. This blade shape shows up in many places, even as far away as Africa, and two thousand years later. Most of the cutting and cut-and-thrust swords have grips that are cast integral with the blade. This is much stronger, as the grip is part of the sword. Of course this also adds weight, and the weight may be the reason that two other methods were tried. One method was the tang construction that was later so successful with steel swords. Alas! Bronze is not as strong as steel, and this too often broke.

The other method was much more successful. In this the grip is made with two extended flanges. Then a piece of material is inserted between them, and the flanges folded over. The material could be plain wood or ivory or any decorative material. These grips follow a timeline. Once the grip was cast integral with the blade, they never went back. But flanged and solid bronze grips coexisted until the bronze sword was replaced by the steel ones.

The cross sections of bronze swords do not vary as much as those later ones made of steel. Indeed, on many of these bronze swords it is difficult to tell what the original shape actually was. A sword could have been quite broad, and yet over years of use be transformed into a much more narrow sword, with much thicker cutting edges. There are swords whose edges are so thick as make you wonder if they were really maces. However, a closer inspection leads one to think that they are swords that saw a great deal of use, and whose edges have simply been worn away. Some blades were made with a well defined central ridge that strengthened the blade. Others had thick diamond cross sections, and still others had thick center sections, and wide flat blades.

The most common form of cross section is that of a raised center section, almost a mid rib, with the blade sloping down to the edges.

[Drawing of a mid rib cross section]

This provided the strength needed for cutting blows. It appears that some swords were made with blades that are thick on the edge, while some have much thinner blades and thin, very sharp edges. It is difficult to tell how much of this is intentional, and how much is due to use, corrosion, and sharpening. Certainly many of them do show file marks. I believe that some swords were made with a thicker edge simply to enable them to cut through some of the armor worn, and I also believe that there are others that were made with thin, flat edges. It should always be remembered that the swords, even mass-produced, were still individual items. A Bronze Age warrior might easily grind and file his sword into a shape that he preferred. (Steel swords would always show a greater variety in shape, since they were individually forged, and bronze weapons were cast). There are a few swords that are flat and would be capable of delivering a terrific cut. How well they would hold up is the question. I do not know of any research along these lines for Bronze Age swords. A larger number of these swords have the flattened diamond cross section of many medieval swords.

I know of two bronze swords that are pure choppers with no capability of thrusting. They are both located in Sweden. Both are large and heavy, and each has a small bronze pellet that appears to be there for weight. One of the swords has two of these pellets and also has a curved section that appears to be for carrying the sword. They are thick and heavy, and it would take a strong man to use them in battle, but they would deliver a blow that would likely not be forgotten.

There has been some confusion regarding some bronze daggers. Early attachments of the handle to the blade with rivets made a very poor juncture. While this is known to have been done, there are many bronze blades that are not properly daggers, but rather what are termed halberds. These weapons had the blade attached at right angles to the line of the hilt. Usually the blades were attached to the shaft by being inserted into a slot in the shaft, and then rivets inserted. This is also not as strong as a socket, but was more substantial than being tied on. The Chinese liked this weapon, but quickly learned to make the halberd with a socket.

FIGHTING WITH THE BRONZE SWORD

Bronze swords were used in conjunction with a shield. The shield is the earliest bit of defensive armor known. Just about everyone used the shield at one time or another. (The Japanese appear to be the only civilized society in which the shield was not in general use at one time or another.) Bronze swords were not designed to be both offensive and defensive weapons, so what happened when someone was caught without a shield is anyone's guess. But the guy without the shield was in deep trouble. With the shield, the fighting techniques were pretty much the same as they were a thousand years later, though probably a little less refined. This would be due to the type of armor more than lack of knowledge or skill.

Although this will be dealt with more fully in a later chapter, suffice it to say that steel armor was more protective than bronze. A steel sword striking a steel helmet was more likely to skip off or fail to bite, so more effort would be made to hit the enemy in the unprotected area, shoulders for instance, than on the head.

However, with bronze it's different. Bronze helmets are not as thick and protective.

[Photo of a reproduction bronze helmet

from the collection of Hank Reinhardt.#342]

A hard blow with a bronze sword could crack or crush the helmet. The sword would be only slightly damaged, especially if it was one with a thicker edge. Armor and helmets were designed for protection against glancing blows, and not for well aimed full force hits. I imagine in the heat of battle there would be a lot of glancing blows. Blows would be coming from all directions, even from those on your own side. Swords would be knocked aside, bounce off of shields, rebound right and left, and be thrown up in spasms as someone was hit and killed. We know that such combat took place from the Illiad and the Odyssey, not to mention pictorial representation on vases, and from other written sources. In short, armor was needed not only as protection from your enemies, but your friends as well. It could not give you complete protection, but it was a lot better to have some protection than none at all.

Although weapons were cast, most of the armor was cold worked. Bronze is easily worked once you realize that it quickly work hardens. Then it has to be annealed. The easiest way to anneal bronze is to heat it up quite hot, and then quench it in water (note that this is the reverse of annealing iron). Helmets and breastplate were forged. The very early armor, like the Dendra panoply, is really rather ugly. It took a good while for them to come up with the muscle breastplate that we all love.

Here weight enters into the subject once again. Bronze is heavy, and the result is that the armor cannot be made too strong, or the weight will be prohibitive. People who get to see a real helmet or breast plate for the first time are usually shocked at how thin the metal is. Thin—but a good armorer would work harden the metal, so that it would be thin, but strong. Not perfect, but a lot better than nothing.

Bronze is a comparatively simple material to work and cast. If you have all the ingredients—the right amount of tin, the right amount of copper, proper molds with gates, and a sufficiency of heat—then your casting is generally going to come out pretty well. During the Late Bronze Age (1550 BC–1200 BC) castings were very good, and it is obvious that the metal workers knew their craft. The one real advantage here is that the swords were consistent in their hardness and their quality.

But even as bronze workers improved their craft, another discovery was waiting in the wings. One that would be the most important ingredient in war even until today. As Kipling phrased it, "Iron—Cold Iron—was the master of them all!"

Suggested further reading by Hank:

Bottini, Angelo et al., Antike Helme. Verlag de Roemisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums, Mainz, 1988.

Byock, Jesse L., "Egil's Bones," Scientific American, Jan. 1995, Vol. 272 #1, pages 82–87.

Peake, Harold and Herbert John Fleure, Merchant Venturers in Bronze. Yale University Press, New Haven, 1931.

Eogan, George, Catalog of Irish Bronze Swords, Stationary Office—Government Publicans, Dublin, 1965.

Eogan, George, Hoards of the Irish Later Bronze Age. University College, Dublin, 1883.

Gamber, Ortwin, Waffe und Rustung Eurasiens. Klinkhardt & Bierman, 1978.

Ottenjann, Helmut, Die Nordischen Vollgriffschwerter der Alteren und Mittleren Bronzeit, Verlag Walter De Gruyter & Co., 1969.

Seitz, Heribert, Blankwaffen. Klinkhardt & Biermann GMBH, Munchen, 1981.

Snodgrass, Anthony, Early Greek Armour and Weapons from the End of the Bronze Age to 600 B.C., Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 1964.

Suggested further reading by the editors:

Buehr, Walter, Warrior's Weapons. Thomas Y. Crowell Company, New York, 1963.

Connolly, Peter, Greece and Rome at War. Greenhill Books, London, 1998.

Macqueen, J.G., The Hittites and Their Contemporaries in Asia Minor. Westview Press, Boulder, 1975.

*If there was moisture of any kind in the mold, the molten bronze would make the mold explode—right in your face. Such a drastic change in temperature between the molten metal and the water always ends with a violent result. It's like having your engine overheat, and then pouring cold water into your radiator; you'll crack your engine block.—Peter Fuller